We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Most of our readers have long since moved on from built-ins, and I have started to move on too, but it never hurts to circle back to some basics. If you’re like a lot of woodworkers, you got inspired to build fine furniture by first learning how to build a library and other built-in cabinetry. Please offer your encouragement and tips, for both built-ins and furniture, in the comments section below!

Tips on How to Build a Library (the Wood Kind)

1. Draw an elevation of the wall you’re going to use. An elevation is simply a scaled floor-to-ceiling view. It will look like a blank box on a piece of paper. Fill that box with the basic outline of the bookcase, then the sub-sections of the case. Your shelf spans (length of each shelf) should be no more than about 36 inches, so this measurement will dictate how many individual cases fill the entire span of the wall.

2. Decide how deep you want the shelves. This measurement will range from 7 to 12 (or more) inches, depending on the size of your largest books.

3. Write a cut list (a list of boards and sizes) for all parts of your bookcases except the case backs and the trim pieces. Just focus on the parts outlined above – the sides, tops, bottoms and shelves. You’ll be cutting these parts out of 4×8-foot sheets of ¾-inch plywood. So the last part of this step is to draw several scaled boxes on a sheet of paper to represent 4×8 sheets, then draw lines to show how you’re going to cut all the boards out of that material.

4. Add the case backs and trim pieces (for the front of the case) to your cut list. You’ll cut the case backs from ½-inch plywood or other inexpensive sheet-sized material. For trim pieces, you can choose from a variety of options at the home center or local lumberyard. You may want to use a decorative moulding for the top and bottom of the case.

5. You’re ready to buy material and start cutting and building. Obviously, this is the most involved step of the process, so my tip here is to find a good book or free online resource for how to build a library. Don’t try to go it alone! Click here for a nice line-up of paid resources in our store.

How to Build a Library (the Paper Kind)

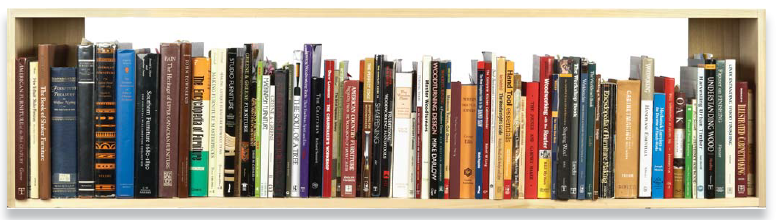

I guess this step is pretty self-explanatory. Go buy books you like! We are releasing a nice collection of woodworking books we like right now. It is a discounted set of classic volumes from Toolemera Press. Buy it today and jumpstart your woodworking library!

–Dan Farnbach

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

I really enjoyed your ‘popular ratio’s’ graphic. That’s going to be very helpful to me in the future. I was therefore surprised that wasn’t incorporated in your brief “how to build a library”. In general, this consideration seems to be present in writing around every imaginable woodworking project EXCEPT bookshelves. Quite by accident, I discovered something you may want to pass to readers. It’s a very simple method to design a bookshelf such that a) the overall width and height ratio is very pleasing, b) the shelf spacing is visually pleasing and c) you get maximum book storage in a given volume. This:

1. Gather a collection of books of all sizes from paperback novels to ‘coffee table’ books. You need a robust sample, 70, 80, 100 books on the widest possible variety of topics.

2. Line them up against the wall by height.

3. Split the line of books into 5 groups by height.

4. Measure the tallest book in each group, add 2″ to each of the five heights.

Step 4 gives you the height of each shelf, inclusive of finger space and the thickness of the shelf. The sum of these plus “top” and “bottom” is the overall height. Now the ‘secret’.

If you’ve collected a representative sample of books, two things will generally be true. First, when you split the line into five, the longest (not tallest) group will give you the ‘right’ width. Second, the ratio of heights of the groups will loosely follow a Fibonacci ratio that is visually pleasing. I’ve talked to several small publishers about this, and none can explain to me WHY this is the case. But, suffice it to say there is some tribal knowledge inside the publishing industry that drives a certain logic with respect to the relationships of height, depth, and width of books. This relationship carries over into GROUPS of books, and therefore into the containers that hold them.

What I find really fascinating about this is the relationship of these sizes to content. They almost follow an Aristotelian logic. Try it, and I think you will find that as a very loose rule, your tall books are topics about either ‘earthy things’ or instructional things in the manual arts. The next smaller group by height has an overrepresentation of text books in math and engineering. As you go down in height, you move through liberal arts, into literature, finally culminating in the shortest group which has an overrepresentation of that fiction which does not quite meet the criteria for ‘literature’. There are exceptions (Loeb Classics for example)—but I contend that as a general guide, the rule holds.

You left out an important part of shelf design, shelf sag.

Sag is important especially in book shelves.

Several years ago someone published a sag calculator “sagulator”, The original website has been removed

but I found a link to an archived copy.

http://web.archive.org/web/20010428125736/http://www.woodbin.com/calcs/sagulator.htm

Using this calculator you may find your 1/2 in plywood shelf may have too much sag

and may not look good.

Al Limiero

Paper libraries are a heck of a lot easier than built-ins!

I find built-ins very difficult, maybe due to the lack of any formal woodworking training. I have a good chance of squaring or correcting my freestanding carcases. My experience with built-ins is that all the work is about making the front look visually correct despite all the bumps, bows, bulges, and previous remodeling bungles. My hat is off to those folks who do it well. 🙂