We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

We visit a manufacturing facility to get the nitty-gritty on making abrasives.

We visit a manufacturing facility to get the nitty-gritty on making abrasives.

In all likelihood sandpaper isn’t made the way you probably think it’s made.

In fact, what is most unusual about sandpaper manufacturing is how similar it is to publishing a magazine. Like publishing, making sandpaper begins with picking the right thickness of paper. There’s ink (the words on the back of your sandpaper). And then there’s the grit and the glue, which to me is similar to the stories we print in the magazine.

If the sandpaper manufacturer uses the right grit and the right glue, then the sandpaper will last a long time, it will cut quickly and it won’t clog. Use the wrong paper, grit or glue and the sandpaper will quickly end up in the trash.

Here at the magazine if we pick the right stories, then the readers keep the magazine for years, and refer to it to build furniture and buy tools. If we choose the wrong stories, the magazine ends up on the floor of a birdcage or around a dead fish.

This spring* we took a tour of Ali Industries Inc.*, a sandpaper manufacturer in Fairborn, Ohio. Founded in 1961, Ali Industries makes the Gator-brand sandpaper for home centers and hardware stores.

*Editor’s note: This article was orignally published in 2009. Since then, Ali Industries has been purchased by Rust-Oleum.

A tour of the Ali plant brought a lot of surprises. I’ve been on dozens of plant tours to see how everything from nail guns to miter saws to universal motors are made. But this is the only tour where the plant seemed a combination of magic tricks and a candy factory.

Pick Your Paper

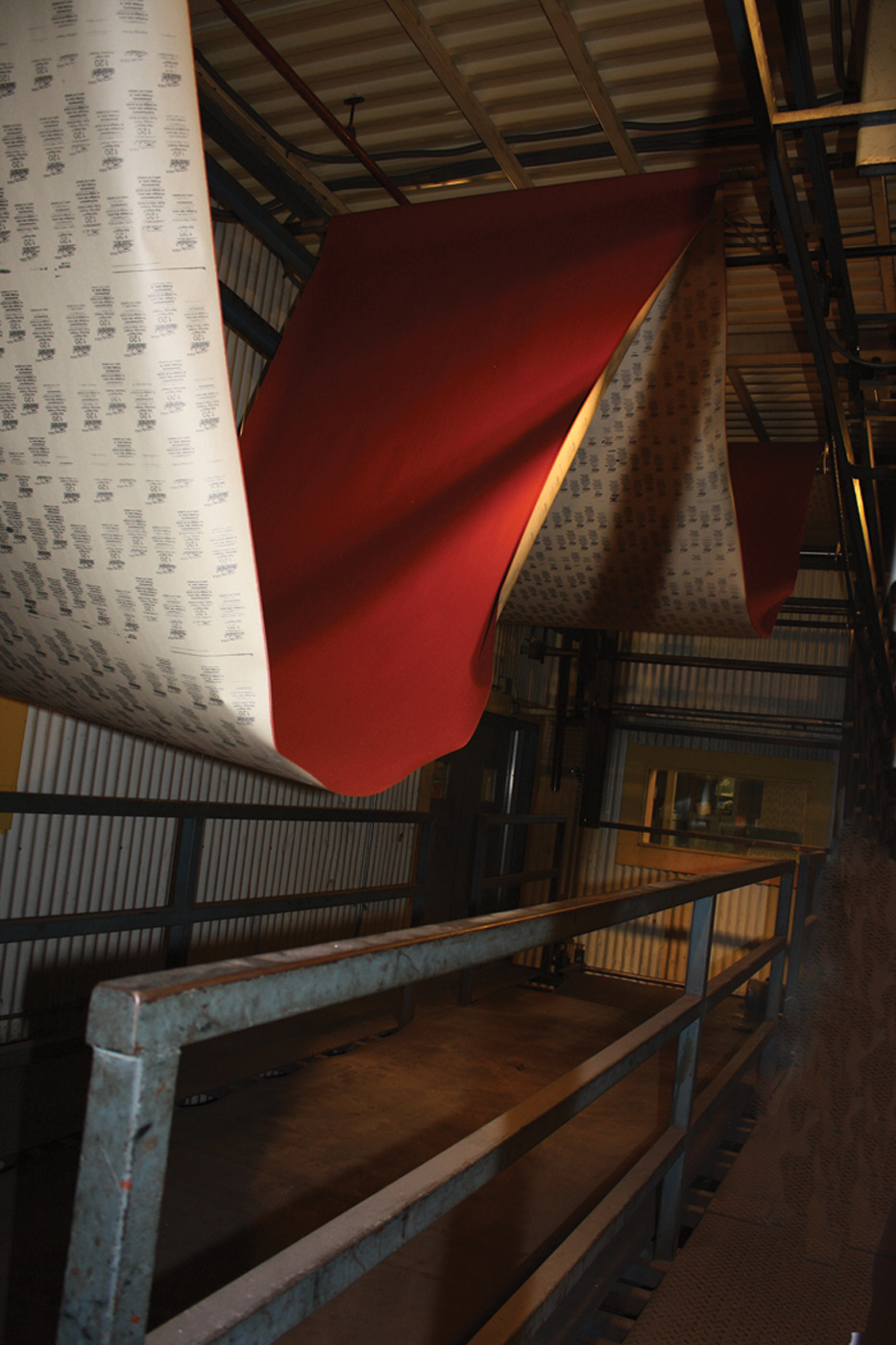

Roll it out. Here you can see the 55″ rolls of paper as they are fed into a printer that inks the grit and brand on the backside of the paper.

Sandpaper can come on different thicknesses of paper (or cloth). The paper’s thickness is graded between A and F, with “A” being the lightest and most flexible and “F” being the heaviest paper. Lighter paper is more flexible, but it also can tear more easily. Heavier paper can be more durable, but it can be stiff depending on the glue used and how the sandpaper is made.

The sandpaper at Ali Industries is “C” weight. Gary Carter, the senior director of sales, says C-weight paper is a premium weight that they’ve treated to get good performance when hand and power sanding.

The paper is in giant 55″-wide rolls and can vary in length from 180 to 500 meters. It begins unspooling on a large horizontal spindle and is pulled first into a large printing press. There the grit number, the brand name and other information is printed on it – then it’s baked with ultraviolet heat so it’s instantly dry.

Glue, Grit Then Baking

From the ultraviolet heater, the paper gets its first coat of glue, which can be a phenolic resin (for sanding discs and belts) or a urea resin, for hand-sanding sheets. During our visit, the resin was a pure red and looked like the Plasti Dip stuff that some homeowners coat tool handles with.

A pot of glue. The red stuff in the tray is the resin. The glued paper travels up out of the tray and into the room where it gets its grit.

The paper descends into the resin on a giant roller that dips the unprinted side into the bath and rolls it immediately upward. From there the flypaper-like stuff rolls into a little room where the magic trick occurs.

Jumping oxide! The stuff on the top rollers is the paper with the resin. The conveyor below it carries the grit. When the grit reaches a certain point it jumps up and embeds itself in the resin.

In a low-ceilinged room under the giant rolling machines the glued paper is brought down parallel to a conveyor belt – about 1″ above the conveyor. On the belt is the loose grit, which could be anything from garnet to aluminum oxide.

Enormous oven. The paper, grit and resin all come into the oven on arms that fold the stuff in undulating curves through the warmed rooms.

At a certain point on the conveyor, the grit is statically charged and it leaps (yes, leaps) up and embeds itself in the resin on the paper above it.

Carter explains that the static charge does two things: One, it causes the stuff to jump in the air. Two, it makes the individual particles orient themselves so the blunt part of the grit becomes embedded in the resin and the sharp point is facing your work.

You can see the grit jumping up into the resin, which is a bit mesmerizing. Any excess grit (there isn’t much) is captured at the end of the conveyor.

It’s officially sandpaper now, but the resin is still wet so the roll of paper has to go into an oven to be baked. The oven looks a bit like a huge taffy puller. Giant mechanical arms loop the paper up and down like ribbon candy and move steadily through the warmed room to the end and back.

More Glue, More Baking

A sharp turn. This machine flexes the finished paper several times to increase its durability. Then the paper is rolled back up.

After the resin is somewhat cured, the paper is coated with another layer of resin, which improves the durability of the paper (only the cheapest sandpaper has one layer of resin). Then it’s baked again and spooled back into a roll. These rolls are heated some more in small rooms to fully cure the resin.

At this point the paper is quite stiff and will crack if bent. So the Ali employees run the rolls of paper through a machine that flexes the paper. These machines bend the paper like a ribbon through a series of turns that makes the product less likely to crack on you.

Then It Gets Complicated

Acres of loops. The white stuff is the “loop” part of hook-and-loop. It’s glued to the back of the paper on this large machine, which also applies the sticky-back glue if need be.

After that, lots of different things can happen to the sandpaper. Employees can add a cloth backing so the sandpaper will be compatible with hook-and-loop sanders. Or they can add a sticky-back coating. But the real variety kicks in when it goes into a warehouse with die-cutting machines.

A giant punch. An Ali employee stacks finished sanding pads as they come out of the die-cutter. The cutter can slice through five or six sheets of sandpaper in one swoop.

Each of these machines is about the size of a small SUV. Five or six rolls of paper are ganged up at the back of the machine. The sheets are pulled into a chamber where a robotic die-cutter punches out the different-sized discs or shapes – for random-orbit sanders, for example.

Making the belts for sanding belts is a little more complicated: They start that process with a parallelogram of paper that is then glued into a tube with some Kevlar tape. The tube is then sliced into the correct widths.

The leftovers. Here’s what the paper looks like after the die-cutter.

Then employees snatch the stacks of finished products, put them in their packages, and the finished goods are boxed up and go off to their final destination. The whole manufacturing process is pretty quick. A typical sheet of sandpaper starts as raw ingredients on one day and within 10-14 days can be ready to ship.

Not only is the manufacturing process fast, but historically speaking, the end product is amazingly inexpensive. Early sandpaper – called “glasspaper” – was pricey, used sparingly, flimsy and never wasted. Nowadays, everyone can afford as much sandpaper as they need, which makes the world a very smooth place.