We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Work with the grain when gluing panels, even when the grain throws you a curve.

When I look at a piece of furniture, aside from its design and craftsmanship, I examine how the wood was used. How was it employed to enhance the design and optimize its appearance? Grain, color and species all contribute to its success. However, one aspect that is often overlooked is the harmonious arrangement of the boards that make up the piece’s larger panels. These could be the panels contained within a door frame or the piece’s top.

Consider the visual appeal of a dining table with a top made of two wide boards instead of one comprised of six or seven narrow boards. The viewer’s eye takes in the smooth flow of that expanse, uninterrupted by the jarring sight of multiple seams, abrupt changes in color, and converging grain patterns and lines. Most people would prefer a top made of fewer boards to one that resembles butcher block.

A table, or any piece of furniture, made of fewer individual pieces of wood, creates a calm, harmonious and luxurious effect, while eliminating unnecessary distractions and visual noise.

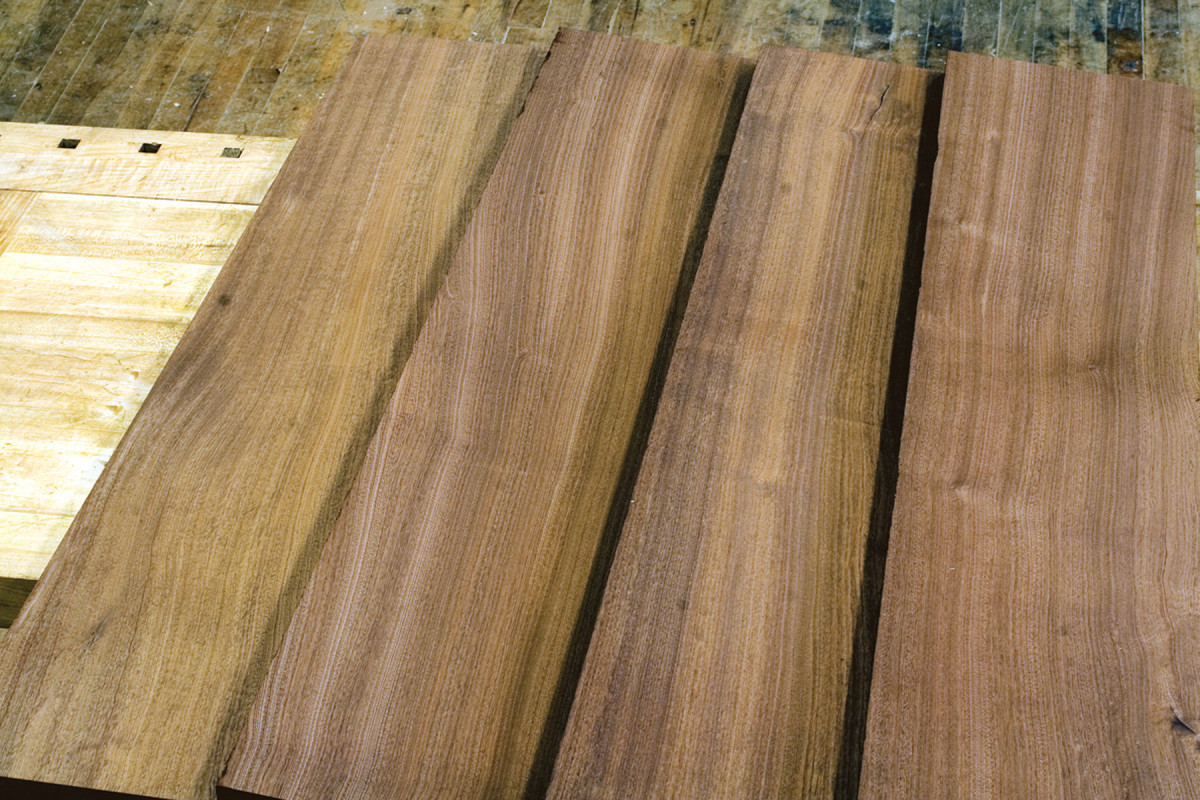

Nice arrangement. Rough-cut boards are arranged for the best color and grain match.

To a woodworker, wide boards can mean an additional expense because most lumberyards and suppliers charge a premium for wide material. Or maybe some trees only grow to a certain diameter. So the supply of wood is restricted to narrow boards. How might a woodworker create a harmonious wide panel or top from narrow material?

If you can arrange the seams of boards to run parallel to the grain, a joint will be easier to hide, creating the illusion of a single board. Sometimes it can be as easy as cutting a new edge. And all that’s sacrificed is a little wood. But if the grain wanders and curves, simply reorienting the edge won’t do the trick.

For this idea to work on a board with meandering grain it would require cutting tight, clean adjoining edges to a curve that follows the grain.

My Method

Double duty. The master pattern lays out a curve common to both boards.

Because the desired curves are subtle, not abrupt or severe, I was able to do away with complex, multi-step templates, cut with multiple router bits using offset guide bearings. This technique is much simpler and faster.

I start out by laying the boards alongside one another and turn them over and end-for-end to obtain the most pleasing arrangement. I look for color, similar grain and grain direction. Once I’ve decided on the order and position of the boards, I look for surface patterns that complement one another. The flatter the curves, the better.

Pattern repeat. After fine-tuning the master pattern outline, transfer it onto a wide piece of 1⁄2″ MDF.

With chalk or a lumber crayon, I draw a curve directly on the boards to indicate where the joint should fall. When laying out the joint lines, avoid abrupt curves that cut severely across the grain (any cross-grain joint will draw attention). You’ll get better results with subtle curves that run lengthwise.

On a 1⁄4“-thick piece of MDF, draw an outline that roughly follows the grain patterns. Cut the outline on the band saw and shape it to a smooth curve. Now place this master pattern onto the board, running with the grain. Adjust its outline to better follow the grain direction.

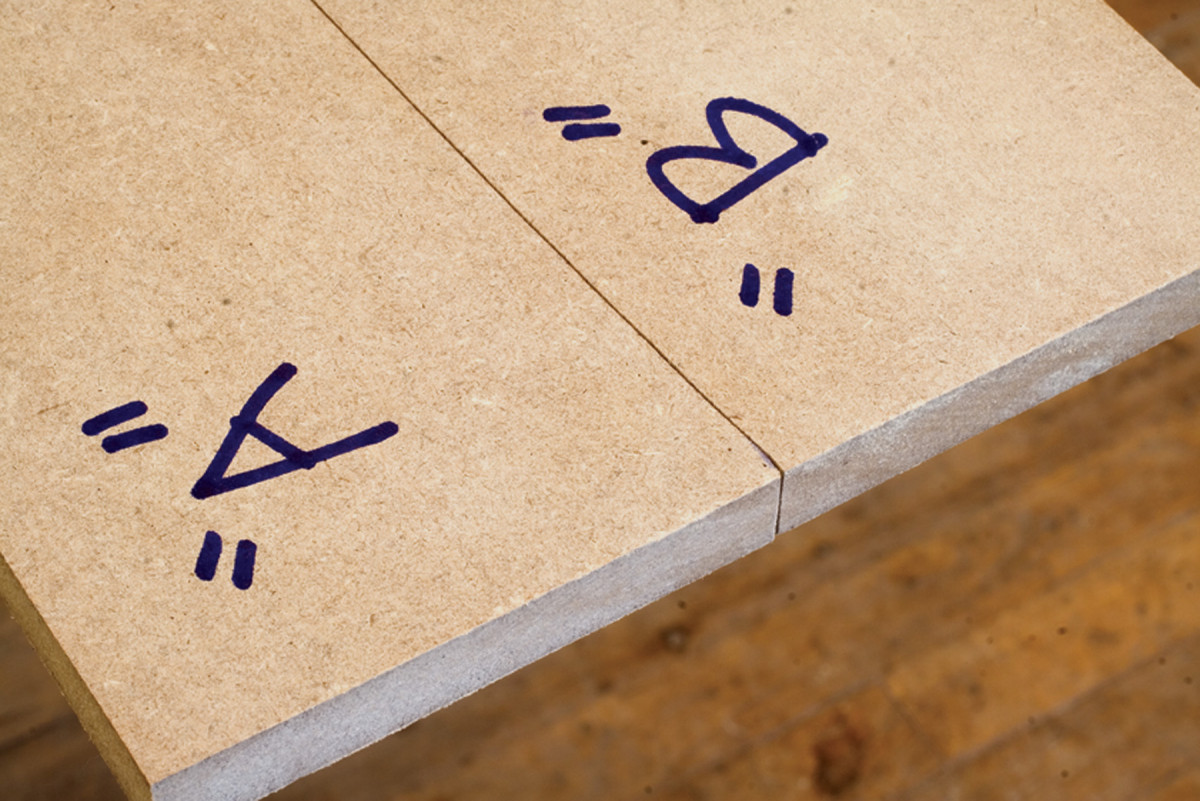

Perfect match. When pressed together, the band-sawn halves (of the working pattern) should come together nicely without gaps or unacceptable roughness.

This is a crucial part of the process. Here is where you “map out” your joints. Ideally, they will be invisible – completely undetectable. But you’ll be pleased with joints that aren’t obvious and are maybe even difficult to find. The eye normally moves in a straight line. And joints running in a straight line are easy to locate and follow. But when the seam curves slightly, the eye loses track of it. Joining boards now becomes a little game: See if you can find the seams.

Making Up Your Working Patterns

Center your master pattern on a piece of 12″-wide, 1⁄2“-thick MDF and transfer the outline. Strive for a single clean, clear line. The next step, band sawing this line, is important because the quality of the cut will directly impact the quality of your joint. The size of the saw you use is unimportant; even a 14” saw will do.

And the size of the blade isn’t as critical as its sharpness. I use a 1⁄4” skip-tooth blade (6 teeth per inch) and obtain great results. Getting a clean working pattern depends on your cutting motion. For the best results, use a continuous and smooth movement when cutting. The cut can’t be doctored afterward. What you get off the saw is what will produce your final joint edge.

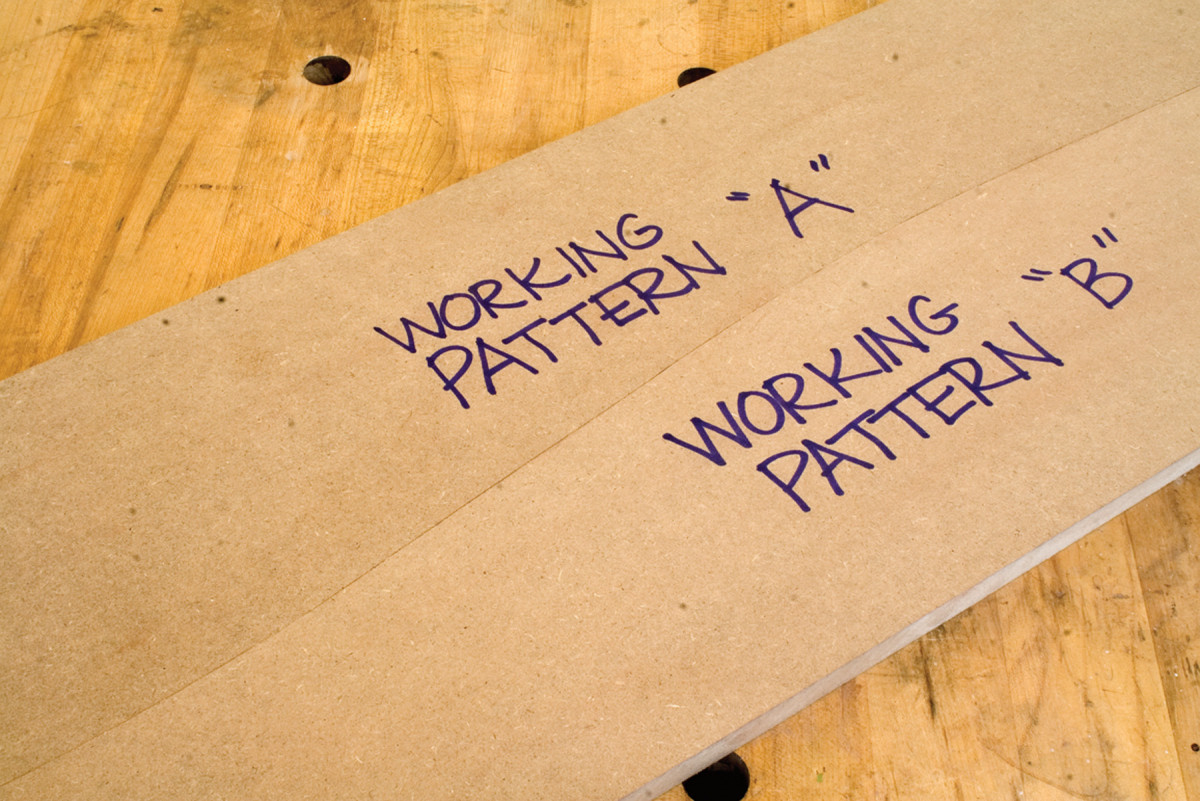

Ready to go. Label each side of the pattern to avoid confusion as you work the joints.

If your cut wanders off the line a little, don’t worry. What’s most important is a smooth cut without jogs, blips or bumpy pauses.

After cutting the outline on the band saw, you should have a pair of complementary working patterns. Pressed together, the two halves should produce a perfect and tight fit, without any gaps.

Rough Cuts

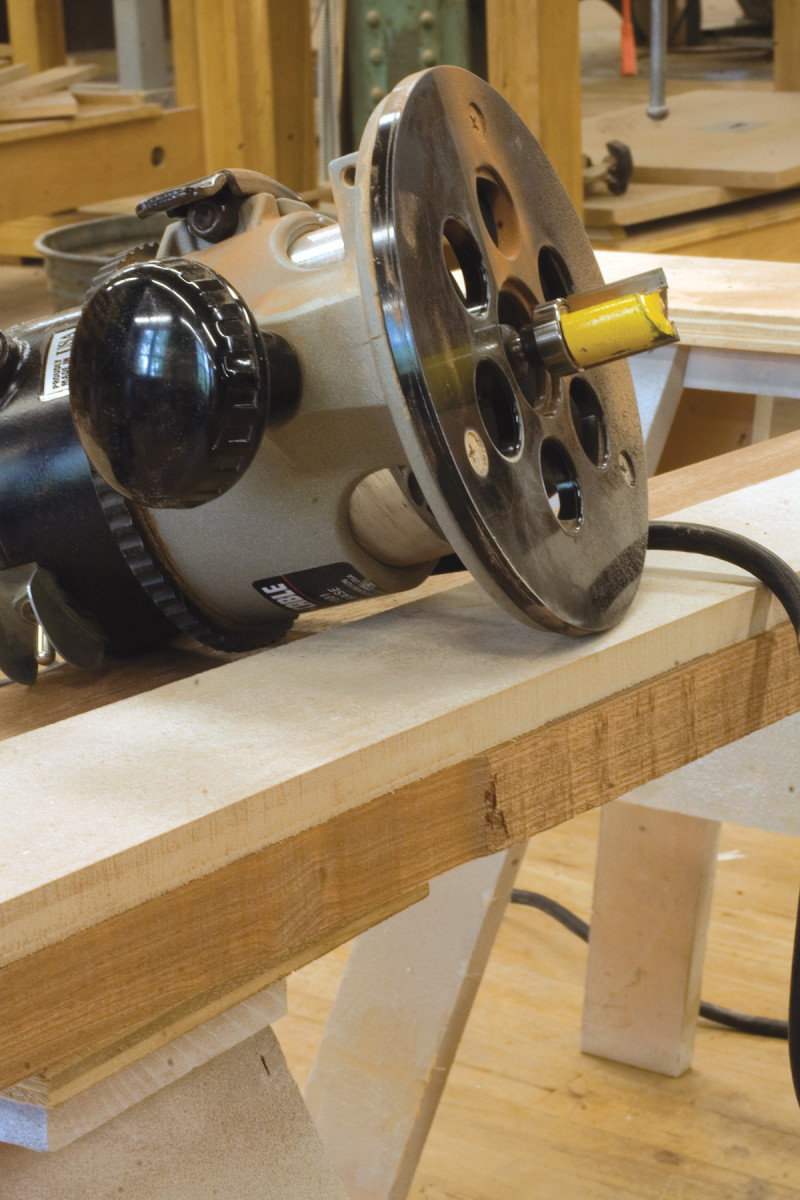

Carefully align the edge of one working pattern with the straightened edge of your board. On the band saw, cut within 1⁄8” of the outline. Securely attach the template to the rough-sawn edge of the board with either clamps or double-sided tape. The new rough-sawn edge should be trimmed clean and flush to the working pattern. For the best results, use a 3⁄4“-diameter flush-trim router bit. The large diameter of the ball-bearing guide will span any small imperfections in the pattern and produce a smooth, flowing curved edge.

Ready to rout. The working pattern should be securely attached to the workpiece before routing. In this case, I used double-sided tape.

Size does matter. A 3⁄4″-diameter flush-trim bit is perfect for trimming the workpiece edge flush to the curved pattern.

When setting up the router, extend the bit to clear the full thickness of your material. Any adjustment to the router bit after you make a cut might produce a stepped edge. The first pass should be light, taking away about half of the waste. The next pass should remove the rest and leave a perfectly smooth edge ready for gluing.

Where’s the joint? Two routed edges, joined together, produce a tight, clean and nearly invisible seam.

The same operation is repeated on the adjoining board with the complementary working pattern. After both halves have been routed, place them together for inspection. The two routed edges should produce a perfect match.

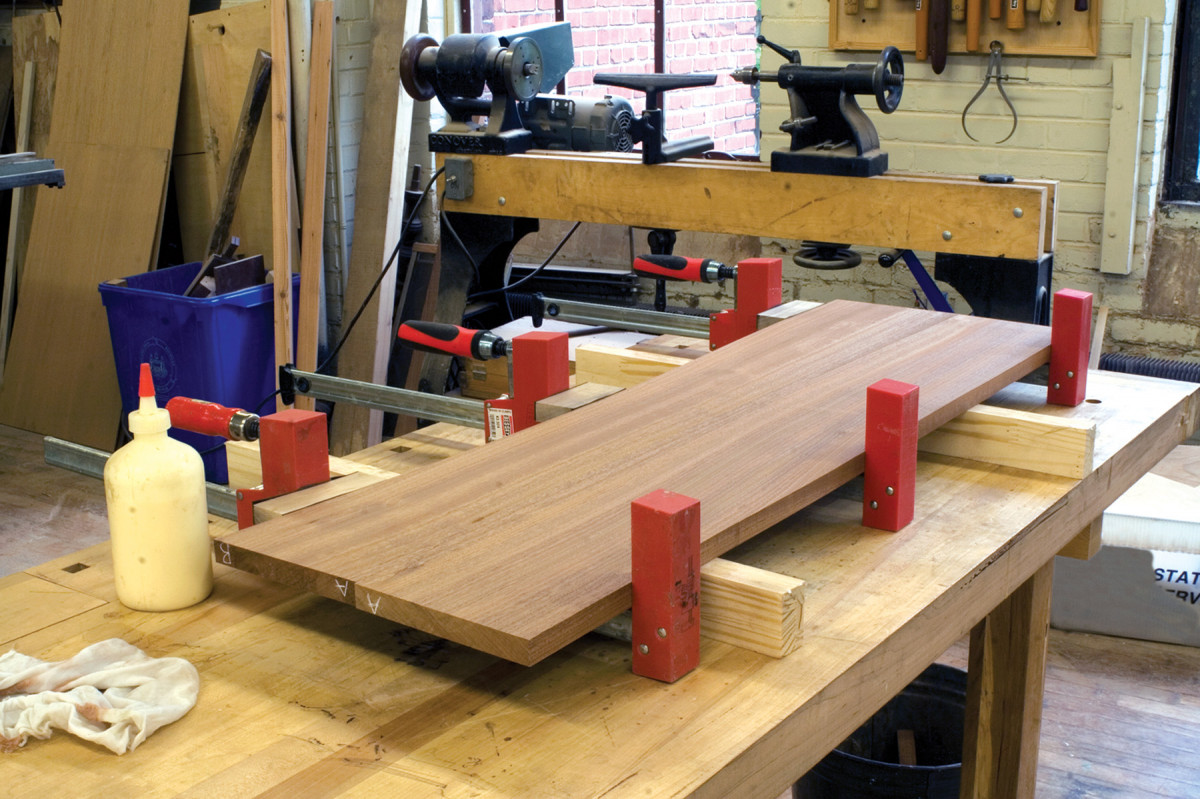

Careful clamping. Rubber-padded cauls are used to prevent clamp marks on routed edges.

If your panel contains several boards, prepare all of the joints before gluing any together. Glue up only two boards (or one joint) at a time. If a project requires more than one routed/curved edge, the remaining edges should be protected from damage with shaped and padded cauls.

Patience pays. Gluing up two boards at a time allows more careful registration and alignment of the joint.

The completed panels should exhibit grain patterns that are complementary, moving in the same direction. The edge of one board should mimic the edge of the adjoining board. The end result should be a panel that creates a sense of calm and balance, giving the impression that it was made up of fewer boards than it actually was.

Unseen seams. Free from harsh colliding seams and abrupt changes in color, the completed top presents a clean and harmonious panel.