We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

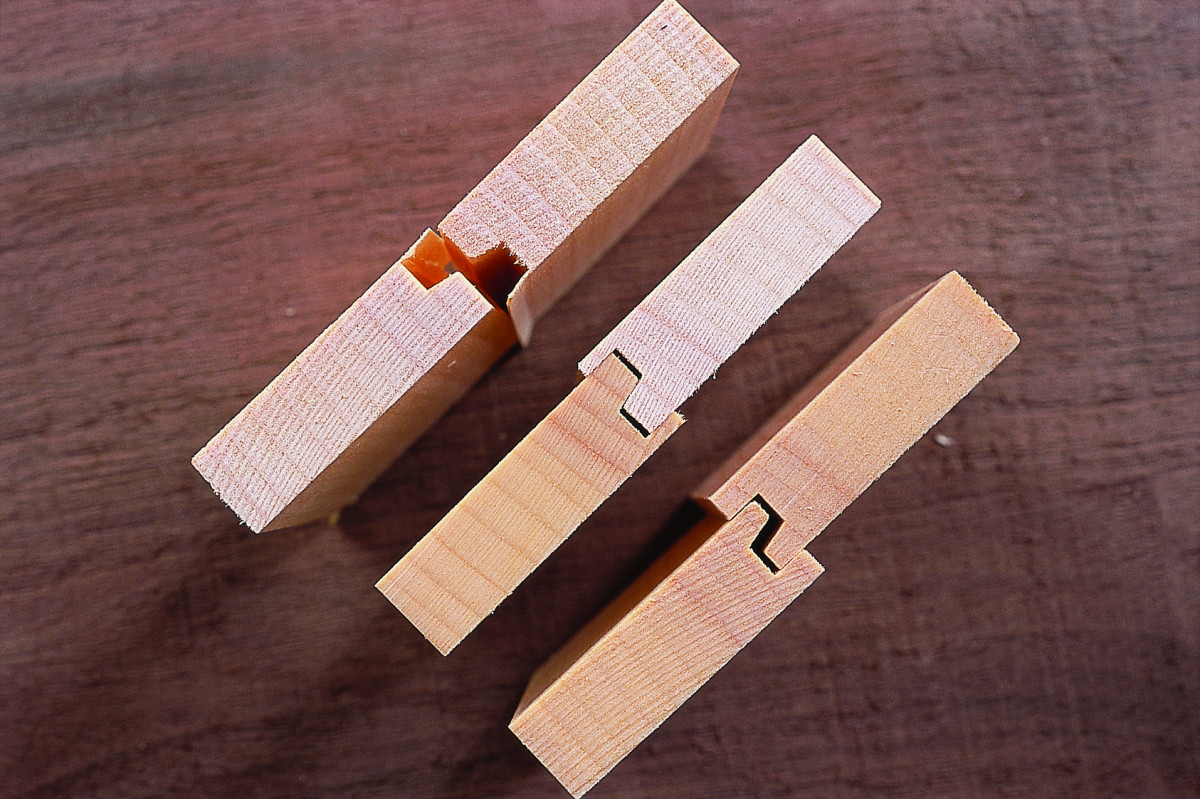

Two ways to cut a drawer-lock joint: The joint at top was made using a drawer-lock bit; the one at bottom was made using a miniature glue-joint bit. Both are strong and quick to make.

A good substitute for traditional methods, this joint is strong and easy to make.

A couple of hundred years ago, most drawers were assembled with hand-cut dovetail joints – half-blinds up front, through dovetails at the back.

But it’s the 21st century now. Many of us don’t have time to hand-cut dovetails. We want something that can be cut fast, assembles quickly and, of course, will stay strong.

The drawer-lock joint is just the ticket. It has an interlock that holds the front and back to the sides and it resists the main stresses administered to a drawer – tension, compression and racking. The finished drawer might not have the pizazz of one assembled with dovetails, but it goes together a whole lot faster.

The Best Bit to Use

Two bits will cut a drawer-lock joint. The miniature glue-joint bit (left) is less flexible on stock thickness but produces a joint with more interlock. The drawer-lock bit (right) is more flexible in terms of the thickness of wood it works with. It cuts joints for both bottoms and corners.

While the routed drawer-lock joint can be produced with two kinds of bits, I am going to focus on the more familiar one, which I call the drawer-lock bit.

This bit is about 1 3⁄4” in diameter with a low body (about 1⁄2” high). Each cutting edge has a protruding tab to cut a single dado.

The other bit you can use is a miniature glue-joint bit. It’s smaller in diameter (about 1″) and the body is taller, about 3⁄4“. It’s designed to produce a routed glue joint on thin stock. While the joint produced is stronger, thanks to the extra shoulder it produces, and it can also cut a glue joint on solid-wood stock, I prefer the drawer-lock bit. It’s easier to set up and will cut all the joinery you need to make a drawer, including the groove you need to hold the bottom in place.

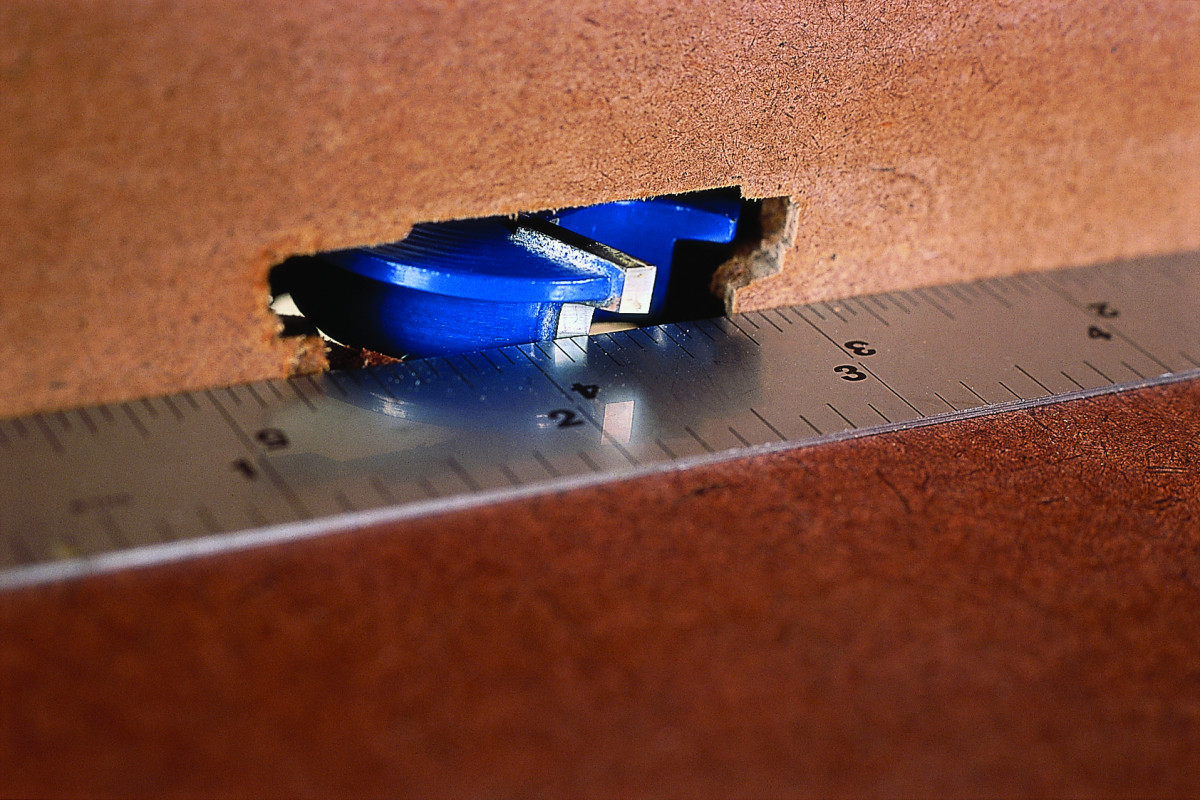

To rout the sides, set the fence tangent to the small diameter of the bit, leaving just the tab protruding. Check the setting with a rule.

Neither bit has a pilot bearing, so you must do the work on a router table using a fence. Because the bits are small, you can use either in a low-powered router run at full speed.

Both bits work the same way. One height setting is used for all cuts. The fence is used in one position for the fronts and backs, and in a slightly different position for the sides.

Setting Up the Drawer-lock Bit

Stand a side on end, braced against the fence, and feed it past the bit. The zero-clearance tabletop and fence surfaces minimize tear-out and prevent catches in the work’s movement.

Start by setting the bit about 3⁄8” to 7⁄16” above the tabletop. As you slide the fence into position, either adjust its facings for zero clearance or apply a strip of 1⁄8“-thick hardboard to it (put the hardboard in place with the bit running so it cuts through, creating your zero-clearance opening).

Adjust the fence so it’s tangent to the bit’s small cutting diameter – just the tab should protrude from the fence.

Make cuts in the edges of two pieces of your stock, turn one over and fit the two together. While the pieces won’t be flush, the interlock should be nice and tight.

If the fit is too loose, raise the bit to tighten the joint. If the fit is too tight, lower the bit. After each adjustment, make additional test cuts to check the fit.

Lay a drawer front or back flat on the tabletop, its end butted against the fence, then feed it past the bit. A back-up block minimizes tear-out and helps keep the workpiece square to the fence.

The only subsequent alteration you’ll need during setup is to shift the fence back when you cut the fronts and backs to expose more of the bit. Use a piece of the side stock as a gauge. Hold it on end against the fence and move the fence until the protruding tab is flush with the exposed face of the stock.

It’s easy to move back and forth between cutting sides and cutting fronts or backs. Check out the series of photos below to see how I make these cuts.

Cutting the Joinery

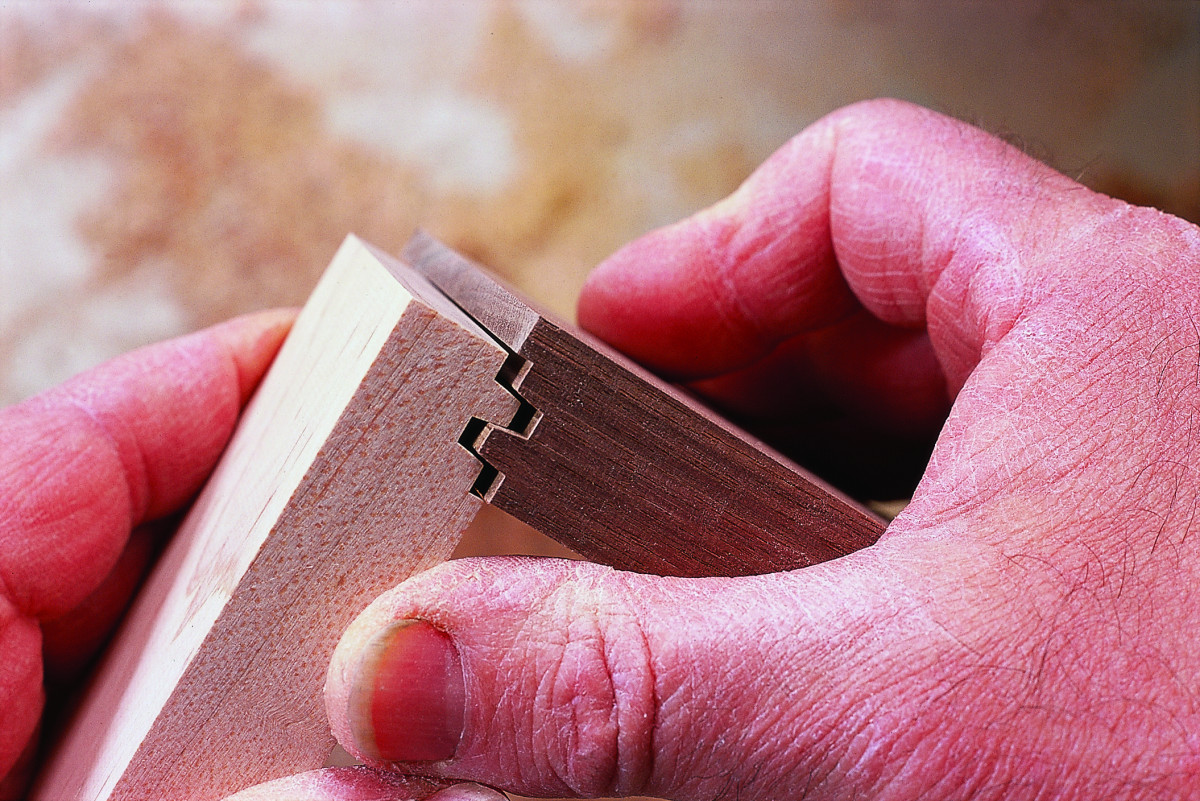

If you’re using a miniature glue-joint bit, tweak the fit by adjusting the height of the bit. The point where the front meets the side must be tight.

Before cutting the joinery for your drawer parts, mill your stock to the final thicknesses and lengths. To determine how long to cut the pieces, especially the sides, make sample cuts in scraps of the working stock.

The thickness of your stock will have an impact on this. If you’re using 1⁄2” stock, for example, the sides generally will be about 1⁄8” shorter than the desired drawer length (front to back). Figure out what it’s going to be before crosscutting the parts and routing the joinery. A workable routine is this:

• Rout the sides. To cut a side, stand it on end with the inside face against the fence and slide it past the bit. Cut one end, then the other. I’ve never found a tall fence to be necessary, nor do I bother with featherboards. If you’re more comfortable with these accessories, feel free to use them.

• Rout the fronts and backs. First, adjust the fence position. The workpiece will rest flat on the tabletop with its end butted against the fence. A square scrap used as a back-up block helps keep the work moving squarely and smoothly along the fence.

Bear in mind here that the thickness of your stock doesn’t impact the joints’ fit. You can mix 3⁄4“-thick fronts with 1⁄2“-thick backs, routing all with the same setup.

• Rip the parts to their final widths.

• Rout the groove for the bottom. Return the fence to the place used to cut the sides. Position the inside face of each part against the fence and cut from end to end with the drawer-lock bit just as it is set. This groove won’t be visible after assembly.

• Mill the bottom so it fits the groove. Keep the bit and fence setting as they are. The 1⁄4” bottom should be face-down on the tabletop as you cut this rabbet.

Putting it All Together

Test cuts, made with the stock flat on your tabletop, help you zero in on the correct height setting of the drawer-lock bit. If the samples won’t mesh (top), the bit must be lowered. If they are gappy (bottom), the bit must be raised. When the setting is right (center), the joint closes tight.

Assembly is pretty straightforward. After doing a dry fit, apply glue to the joints and put the parts together. I glue a plywood bottom into place, regardless of the stock used for the sides, front and back.

With the drawer bottom face-down on the tabletop, rout all four edges. The rabbet will fit the bottom to the grooves cut for it in the fronts, sides and backs using the same bit.

In keeping with the “make ’em fast” mind-set, I’ve taken to shooting two or three brads into each joint. Glue holds the parts together, but the brads eliminate the need to clamp up each drawer, saving a lot of time.

To do this, first join a side to the front. Then set the bottom into its grooves and add the back. Next, drop the second side into place. Check for square, shoot brads into the two remaining corners and your drawer is assembled and ready for fitting.

The drawer-lock joint works on inset drawers with integral fronts (shown here) as well as on drawers with lipped false fronts.

If you don’t have a pneumatic brad nailer, you can use masking tape to “clamp” small drawers. But if you’re making larger drawers, you ought to use parallel-jaw clamps or bar clamps. Just apply pressure from side to side; front-to-back clamping is unnecessary.

In the end, when the drawer is fitted to the case, shellacked and loaded up with whatever you’ve decided to store there, it’ll perform as well as the ones you devoted hours crafting with dovetails. And the proof is in the performance, right?

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.