We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Bodger and blacksmith Don Weber shows how to effectively combine power and hand-tool techniques to build a simple and sturdy toolbox.

Bodger and blacksmith Don Weber shows how to effectively combine power and hand-tool techniques to build a simple and sturdy toolbox.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the April 2005 issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine.

I’m a bodger and a blacksmith, making tables and chairs in iron and wood. When I’m not in the shop, I’m journeying to woodworking shows to demonstrate the spring pole lathe or teach workshops in traditional woodworking and metalsmithing. I travel quite a bit, and if you’ve ever watched the way the baggage handlers deal with your luggage, you’ll understand why I built an oak box banded in iron to carry my woodworking tools.

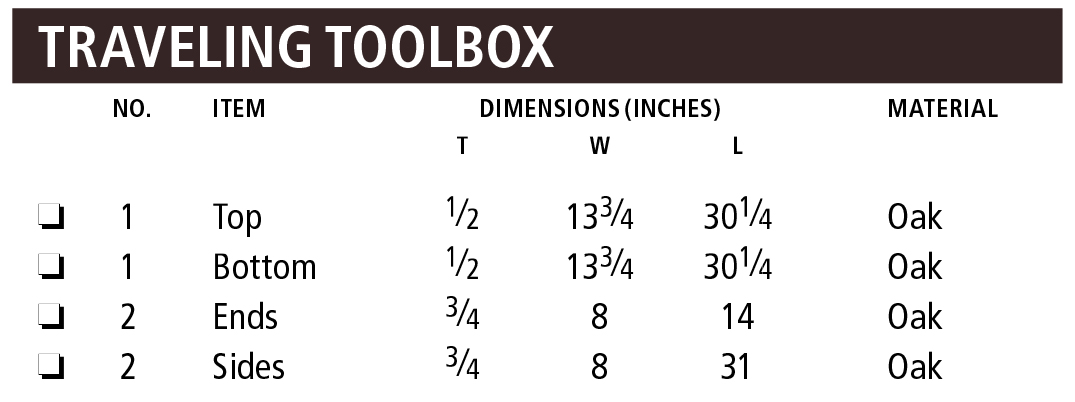

The toolbox described here was made of quartersawn oak from a winery in northern California. I’ve built instrument cases for rare and antique musical instruments, and I’ve found the lid moved considerably with humidity changes. So with this toolbox I’ve allowed the top and bottom to float in a groove in the sides and ends, much like a frame-and-panel door.

I had the oak boards resawn to 1⁄2” thick. All the joinery was done on a table saw with the help of a rebate plane (here in America we call a “rebate” a “rabbet,” but I prefer the traditional English term, rebate), a Stanley No. 5 (jack plane) and a low-angle block plane. I reinforced the corners of the box with 1⁄8“-diameter locust pins because I forged corner brackets (not shown here) as well as the hinges, latch and handles. (I’ve been influenced by the Tansu hardware of Japanese chests.)

Edge Jointing by Hand

Edge Jointing by Hand

I use my jack plane to joint the edges of the side boards. The plane’s iron is slightly cambered across its width to allow me to correct an out-of-square edge.

The top and bottom panels were made by gluing up two boards edge-to-edge. I prepare the edge for gluing with my jack plane (Mr. Jack, I call him). Cabinetmakers of old would use a longer jointer plane, but a board of this length can be accurately planed with the shorter jack. Use your fingers as a fence along the face of the board as you plane each edge. Check your results with a try square.

If you’ve done a good job with the plane, you should be able to create what we call a “rubbed” joint. This is where you glue each edge and rub the mating edges together until the glue begins to set up. A clamp or two is a good idea while the glue cures.

Rebates by Hand and Power

When gluing up a panel, I rub the glue joint up and down to ensure a gap-free joint.

I cut the rebates on the side pieces by first defining the joint’s shoulder with my table saw and then reducing the thickness of the tongue with my rebate plane, a vintage Record No. 778. Set the height of the table saw’s blade to half the thickness of the stock of the sides and ends, which is 3⁄8” in this case. Set the rip fence so your rebate will be 3⁄4” wide. Cut the shoulder on the ends of the sides. Now reduce the thickness of the joint with your rebate plane.

For those purists out there, you can cut the rebate entirely with a rebate plane (or a Stanley No. 10, a carriagemaker’s bench plane). Just be sure to use the plane’s side nickers to score across the grain to prevent your grain from tearing out as you cut the joint.

A couple clamps across the joint are good insurance – even if you have a good edge joint. The cauls keep the panel flat.

The edges of the top and bottom panel were rebated all around in the same manner to fit in the groove cut in the sides and ends of the box. I set the raised portion of the panels so they are flush with the top and bottom edges of the sides. Note that the rebates on the ends of the panel are 3⁄8” wide. The rebate on the long edges is a different width, 1⁄4“. This arrangement allows the panel to expand across its width but not along its length. And that is proper cabinetmaking.

Chamfering the edges of the top and the raised panel with a block plane softens the look.

A small chamfer is planed around the inner sides of the box frame, and the raised portion of the top and bottom to create a visual break when the panel moves with humidity variation.

Plowing the Grooves

The top and bottom panels are fit into the grooves in the sides and ends. You could cut this groove using your table saw. But if you have a plow plane, this is the place to put it to use.

Start the plane at an angle as shown. After each pass bring the tool a bit more level. This makes a square joint.

The plow plane is designed to cut grooves of different widths, which are varied by changing the cutter in the tool. The location of the groove is determined by the tool’s fence, which bears against the edge of the work during the cut. The depth of the groove is determined by the tool’s depth stop. Once the joint reaches its final depth, the tool will then cease to cut.

Glue, Drill and Peg

Glue and clamp the ends to the sides with the top and bottom panels in place. Be careful not to get glue in the groove or the panel can’t expand and contract as it needs. When the glue has cured, drill 1⁄8“-diameter holes in the corner joints to accept the 1⁄8” locust pins.

Here I’m using a hand drill (sometimes called an eggbeater drill) to bore the pilot holes for my locust pins.

The top is cut away from the glued-up box 11⁄2” from the top edge, using a table saw. After the first two cuts are made, wedges are inserted in the slots to keep the saw blade from binding. A few pieces of masking tape keep the wedges in place.

Carefully part the lid on the table saw with wedges to hold the kerf open.

With the saw cut complete, clean up the tooling marks on the top and bottom using a plane, scraper or (my favorite) a small scraping plane.

Once the lid has been parted from the bottom, plane or scrape the sawn edges of the toolbox to remove the tooling marks.

The hardware for my box was hand forged in my blacksmith’s shop, though there is some decent hand-wrought hardware out there. To fasten the handles to the box, I added a 1⁄2” x 1⁄2” ledger to the inside of the box to strengthen the attachment of the handles as well as providing a ledge for a tray for small tools.

All surfaces were dressed with a cabinet scraper and finished with an oil varnish (one pint Marine spar varnish, one pint boiled linseed oil and enough gum turpentine to thin to the consistency of half-and-half).

Once rubbed up with a Scotch Brite pad and some Briwax, the job is done. I have done a lot of traveling with this toolbox, inevitably filling it with more tools than it should carry and it is still doing its job admirably.

Extra: The Plow Plane

In this article I mention the use of the plow plane to create the grooves necessary to house the top and bottom panel of the tool chest. Here are several passages from the book “Planecraft: Hand Planing by Modern Methods” by C.W. Hampton & E. Clifford (C. & J. Hampton), originally published in 1934. My edition was published by Woodcraft Supply in 1972.

In this article I mention the use of the plow plane to create the grooves necessary to house the top and bottom panel of the tool chest. Here are several passages from the book “Planecraft: Hand Planing by Modern Methods” by C.W. Hampton & E. Clifford (C. & J. Hampton), originally published in 1934. My edition was published by Woodcraft Supply in 1972.

“The modern joiner and cabinet-maker accept the plough as an essential tool in the kit, for without a tool that will make a groove of some sort all work would be very limited; yet there was a time when woodworkers had no such tool. Constructions prior to the 15th century are without grooves. How is it then that the plough has become so necessary a tool since that time?

“Probably in no better way is this question answered than in the evolution of the chest – that simple box-like structure from which practically all our modern furniture can trace its ancestry. Chests may be traced back to the 13th century, many of the earlier ones being laboriously “dug out” from a solid baulk of timber, and strongly bound (for conditions were rugged, rough, and precarious in those days) with iron bands. A natural progression from this was a chest nailed up from boards; and a few such chests are still preserved in some of our churches and museums. If an examination of these is made, it will be found that, as a rule, the front and back and the bottom are single boards with the grain running vertically; and it will be found in most cases that the front and back boards are split. This of course is natural, and to be expected, for wood naturally shrinks across the grain, but very little along the grain, and as the boards of the front are nailed across the grain, but very little along the grain, and as the boards of the front are nailed across the vertical long grain ends, when shrinkage occurs, something has to give way. Hence the carpenter sought out a way of preventing this damage.

“The practical outcome was the invention of a panelled construction, a construction which is standard practise to this day. If the wood could be free to shrink (and for that matter to expand also – as in a moist atmosphere) the problem was solved; and a frame, grooved for a panel, offered the solution. So in the 16th century we find chests the back and front of which are panelled, whilst the ends remained solid … Perhaps the first grooves were made with a scratch tool, for the ancestry of this tool goes far back – it was used for mouldings long before moulding planes were common. Yet a scratch tool has its limitations, and it is never a happy tool to use in any case, and so a plough plane made its appearance.“

The plow plane is a chisel-like plane with an adjustable fence and depth stop. The wooden variety had wooden threaded rods extending from its sides to secure the fence so that the groove could be set a fixed dimension from the edge. The Stanley No. 45 and No. 55 were metal versions of the old wooden plow planes, kind of like a pair of skates with a tooth sticking out the bottom, and lots of adjustment screws, etc. Most of the cutting was done with the grain. But with the use of spurs (also called nickers) attached to the side of the plane it would score the wood across the grain as well. You could cut a groove with a marking gauge (to define the shoulders) and a chisel (to remove the waste between the lines).

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

Bodger and blacksmith Don Weber shows how to effectively combine power and hand-tool techniques to build a simple and sturdy toolbox.

Bodger and blacksmith Don Weber shows how to effectively combine power and hand-tool techniques to build a simple and sturdy toolbox.