We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Trading Wall Street for molding planes.

Editor’s note: This interview originally appeared in the October/November 2012 issue of American Woodworker

Matt Bickford’s story is quite unusual for a guy in his thirties. He used to be a “market maker” in one of the most competitive environments in the world of finance, living in a big city (Philadelphia) and drinking coffee constantly—“Just to stay alert,” he recalls. And then, kaboom! He leaves Dow Jones behind, moves his family to a small village in Connecticut and sets up shop making wooden molding planes.

A Late Bloomer

Molding planes allow duplicating virtually any profile.

Many woodworkers discover woodworking early in life. Not so with Matt. Although he grew up around early 19th century furniture reproductions, played with puzzles, and built things with his father (an engineer), Matt didn’t develop an attraction to woodworking until much later. His first serious connection occurred when he visited Don Boulé, a cabinetmaker in Haddam Neck, Connecticut, and an old family friend of Matt’s wife. During one of their vacations in Haddam Neck, Matt was invited to Don’s shop, where he saw a magnificent sleigh bed with ornate details and carved finials. That bed changed Matt’s life.

Round and hollow molding planes are sold in pairs and available in widths ranging from 1/16″ to 1-1/2″ radius. They’re used individually or in combination to shape the curved surfaces of moldings as quarter rounds, coves, bullnoses, side beads, ogees, astragals and ovolos.

While one of the bed’s massive side rails was almost completed, the other rail was unfinished—laid out, but waiting to be carved. “I was hooked at that moment”, Matt says. “Up until then I had no idea how sophisticated and beautiful the art of furniture making is, how pieces are built and what’s involved in making them. Before, I just took things for granted, like using a computer without knowing how it works or what goes on beneath the keyboard.”

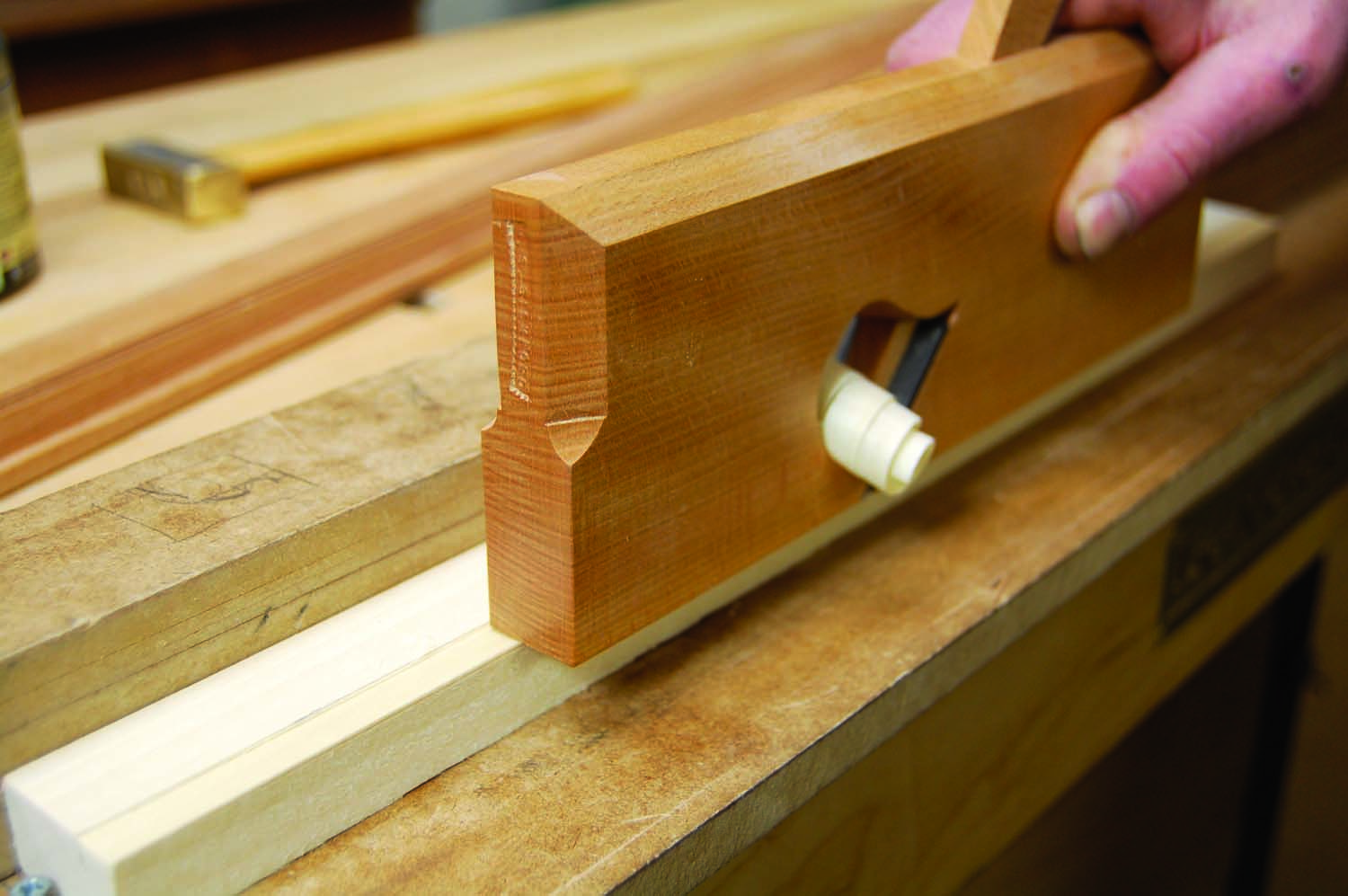

Rabbet planes are used to make rabbets and fillets in moldings and to create steps for round and hollow planes to follow in complex contoured moldings. They can also be used on-edge, in lieu of a snipes bill plane (see below), to define gauge lines to guide subsequent cuts.

Seeing Matt’s excitement, Don invited him into his house to view the rest of the collection that he and his son Chris have been building over the years. Matt was so taken by the evening’s events that he stopped to buy a tablesaw—his first woodworking tool—on the way home.

Dedicated molding planes allow cutting a specific profile with a single plane. This plane cuts a 3/4″ ogee with a fillet.

On his next vacation to Haddam Neck, and the many that followed, Matt became a de-facto apprentice in the Boulé shop, gradually developing skills and learning to appreciate tools and techniques. His days were spent helping with whatever was on Don’s to-do list, from sanding and knocking out corners to jointing and planing. In the evenings Don tutored Matt via private lessons in fine woodworking techniques such as hand-cut dovetails, carving, and turning. “We worked during the day and ‘hobbied’ at night” Matt recalls. “Ten years later, we still do the same thing.”

When Matt started to study woodworking, his goal was to make a Chippendale chair like one he’d seen in Don’s shop. “When you see a highly curved hand-made Chippendale chair for the first time, and all you used to know was machine-made Queen Anne furniture, your base for appreciating taste, style, and craftsmanship is forever shifted,” he states. Matt chooses to build tour de force period reproduction pieces. Taking on such challenging work is a great way to continuously develop and refine one’s skills in the art of furniture making, he says.

A Plane Maker

As Matt grew more immersed in the craft, he found that he needed more and more dedicated router bits to correctly mill the molded edges that were required to accurately reproduce each period piece. He also discovered that many of the original drawings and actual moldings on genuine period pieces required shaped details that didn’t exist in the fixed canon of commercial carbide bit profiles. “The idea of spending $30 or $130 dollars on a new bit that’s only close to the edge that I want is discouraging,” he says. “Making a tall case clock or a large secretary that has a wide crown molding with eight different levels is out of the question; it would cost hundreds of dollars for shaper knifes to run 4′ of molding that you’ll never use again.”

So, Matt decided to try the tools cabinetmakers had used for centuries: molding planes. “You can put them to work to make a really elaborate compound molding that includes six, seven, or eight steps,” he says, intently. “Then, on another occasion, you can incorporate some or all of the planes to make a totally different profile. With a set of molding planes, you can do so many things!”

Matt started buying molding planes online and at flea markets. As he began to realize their potential, he started to think about making them from scratch. It just so happened that as Matt was contemplating making his own planes, Lie-Neilsen Toolworks released three items that made it possible, a DVD on how to make molding planes, tapered tool-steel plane-iron blanks, and floats, the tools used to cut, flatten and smooth the bedding for the plane iron and other critical parts of a wooden plane.

Two other coincidences occurred on Matt’s journey to becoming a plane maker. As a member of a Philadelphia woodworking club, he had started to give demos on traditional woodworking techniques, including the use of molding planes. One night, Chuck Bender, a local period furniture maker who was a guest at the meeting saw Matt’s planes and asked if Matt would make him a set. Matt originally declined, but a year or so later, Chuck saw Matt again and repeated his request. Coincidentally, Matt had just decided to leave his stock market job and move to Connecticut. At this watershed moment, Matt became a plane maker.

Making a Moulding Plane

Photo 1. To make the rabbet plane shown here, the first step is to protect the edge from long-term wear by embedding a ledge of end-grain persimmon. Then the mouth for the plane iron is precisely cut at the proper angle.

Matt’s shop is at home in Haddam Neck, divided between the basement (“My dungeon,” he laughs), where he mills the wood for his planes, and his upstairs studio, where the plane fabrication takes place. The Bickford family—Matt and his wife have three boys—resides between the two shop levels.

Photo 2. The housing for the blade’s shaft and the wooden wedge that secures it is drilled and then carefully shaped with floats, tools specifically made for this critical work.

Matt makes most of his planes from quartersawn American beech, a dense hardwood with an important characteristic for wooden plane makers: beech uniformly expands and contracts throughout the plane’s body with seasonal changes in humidity. Thus, a beech plane will not become thinner in the middle than at the ends, deforming its geometry and degrading its performance. Cherry and other fruitwoods share this characteristic, which makes them good substitutes.

Photo 3. The plane’s wedge is tapered to fit the housing so it will lock the blade’s shaft in position.

Matt initially shapes the wooden blanks with machines, but he spends most of the production time using handsaws, chisels and floats to precisely shape the housings in each plane body for its iron and wedge (Photos 1–6). Each of Matt’s planes includes a beautiful escapement, an artfully shaped opening above the blade that directs the shavings out and away from the tool. For the blades, Matt uses Nie-Nielson O1 tapered tool steel iron blanks, which he individually shapes, hardens and sharpens for each plane. In his premium rabbet planes, Matt embeds (or “boxes”) a persimmon end-grain ledge to protect the plane’s edge from long-term wear.

Using Molding Planes

Molding planes cut flat, groove, cove and bead profiles, which are combined to make moldings of all shapes and sizes. A rabbet, one of the most basic molding profiles, is also used to stage more complex profiles. To cut a rabbet, place the molding blank on a long board that’s clamped to the workbench. Supporting the blank along its entire length allows creating moldings from even the thinnest and most delicate stock. Use a bench dog or install two screws at the end of the blank to keep it from moving as you plane.

Photo 4. The plane iron blank is shaped, hardened and sharpened.

Start by using a marking gauge to establish the rabbet’s width. Then, follow this line to cut a tiny groove parallel to the edge. Matt calls this the “gauge line.” A snipes bill plane is specifically designed for this purpose, but a rabbet plane can also do the job: Place the rabbet plane’s boxed edge on the gauge line, tilt the plane and make one or two strokes to create a v-groove.

Photo 5. The plane’s sole is flattened with the blade installed, but recessed.

Next, stand the rabbet plane vertically and plane end to end to form the rabbet. “Use your fingers underneath the plane to act as fences to control the rabbet’s width,” Matt says. “The grooved gauge line provides room for error.” To complete the job lay the rabbet plane on its side in the rabbet, so you can use it to clean the rabbet’s shoulder and cut it flush with the gauge line.

Photo 6. During use, the plane’s escapement funnels shavings out and away.

Creating a more complex molded profile is a process of incremental reduction, according to Matt. He draws the molding’s profile on the end of a blank. Then he uses the profile’s transition points to create a series of steps (rabbets) that allow removing all the waste. Once the steps are established, they’re left as fillets or shaped with round or hollow planes to form the molding’s convex or concave profiles.

Visit msbickford.com to learn more about Matt’s molding planes.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.