We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Go with the flow. Sweet curves can flow from your compass into your work with a bit of practice.

Practice is the best of all instructors.

Maynard lived next door. When he wasn’t spinning wrenches at the local Ford garage, he was out in his driveway, hunched over a neighbor’s car.

As a kid I spent hours leaning over a fender, watching him perform what seemed like magic. I thought he could fix anything and peppered him with questions, but his answers always ended with the same admonition: “It takes practice.” That’s not an answer I wanted to hear then and, to be honest, it’s not what I like hearing today. Who wants to practice? Can’t we just skip it and get to the fun stuff?

There are two schools of thought about becoming a master at an art or craft. Both involve practice.

One notion, affirmed by centuries of traditional apprenticeships, says that mastery is less dependent on talent than just putting in the time. Writer Malcolm Gladwell claims it takes around 10,000 hours of practice to reveal the potential hidden in an average person pursuing excellence in a specific area. This would come as no surprise to our ancestors who trained in traditional apprenticeships, beginning at around 13 years old, for five or six years before progressing to journeyman status.

The other approach holds that we make huge strides toward mastery by breaking core skills into bite-sized pieces that can be practiced deliberately over time. Entrepreneur Jim Rohn, no stranger to the concept of success, once wrote, “Success is nothing more than a few simple disciplines, practiced every day.”

But it’s not just about putting in the time, it’s about focusing on specific lessons. In fact, we gain nothing and may even go backward by putting in large chunks of time on the wrong things while ignoring fundamental core skills.

I imagine you have seen, as I have, woodworkers with very high technical ability gained through many years of effort, yet who lack simple design fundamentals that would showcase their ability. Without a solid base of core design skills, no amount of precise workmanship will make up for that deficit.

This bite-size practice of core skills is something we do all our lives. We may master a foundation skill, such as proportions, then return to re-learn it when our work evolves to a different place.

Core skills never change, but our application of them may shift as our skill level progresses. For example, we return to the core skill of understanding proportions again and again as we explore working at different scales or experiment with curves or organic forms. The assumption is that if we want to always get better, our core skills such as drawing will also need to get better. Thus we commit to improving those core skills by intentional practice.

The good news is that it’s fully possible to improve our abilities in rapid strides. The bad news, though, is that mastery – in design or any other skill – is linked to deliberate practice. No one (yet) has come up with a method to instantly transform someone into a great designer. Mastery is a structure built brick by brick.

The Core Skills

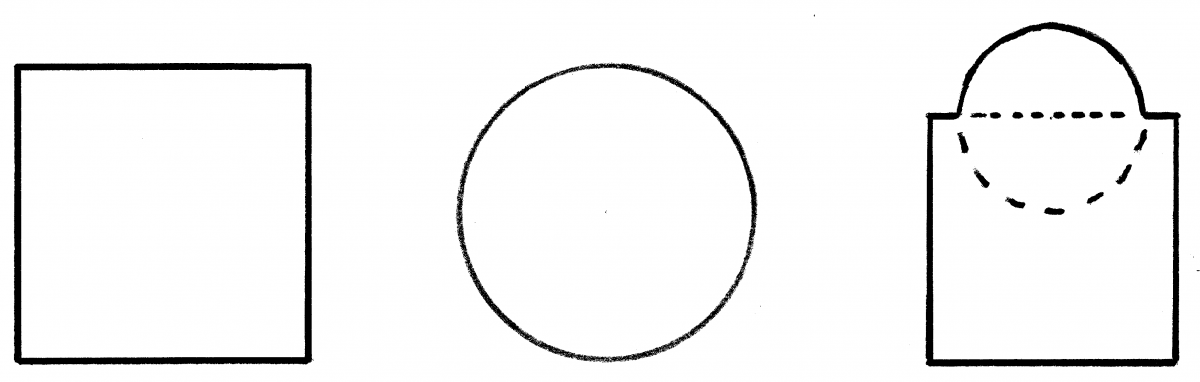

Shape up. Understanding the simple shapes that inhabit a design is a key skill.

Fortunately, we are not talking about practicing and mastering a long list of core skills – five or six are usually sufficient. For woodworking in general, examples of core skills might be sharpening, stock preparation or joinery. Do you see how each of these can be broken down into small, easily practiced pieces?

If we treat design as an area of mastery, there are six core skills to focus our attention on: proportions, lines and simple shapes, drawing, space, curves and forms. Longtime readers of this column will note my tendency to revisit these skills.

What follows is a summary of each core skill, broken down into bite-sized bits.

Proportions are the patterns we use to tell a story and give the eye footholds within a design. They include whole-number harmonic proportions, and how these patterns relate to the human form, nature and architecture. Proportions are woven into each and every core skill and, for that reason, are critical to all other skills that follow.

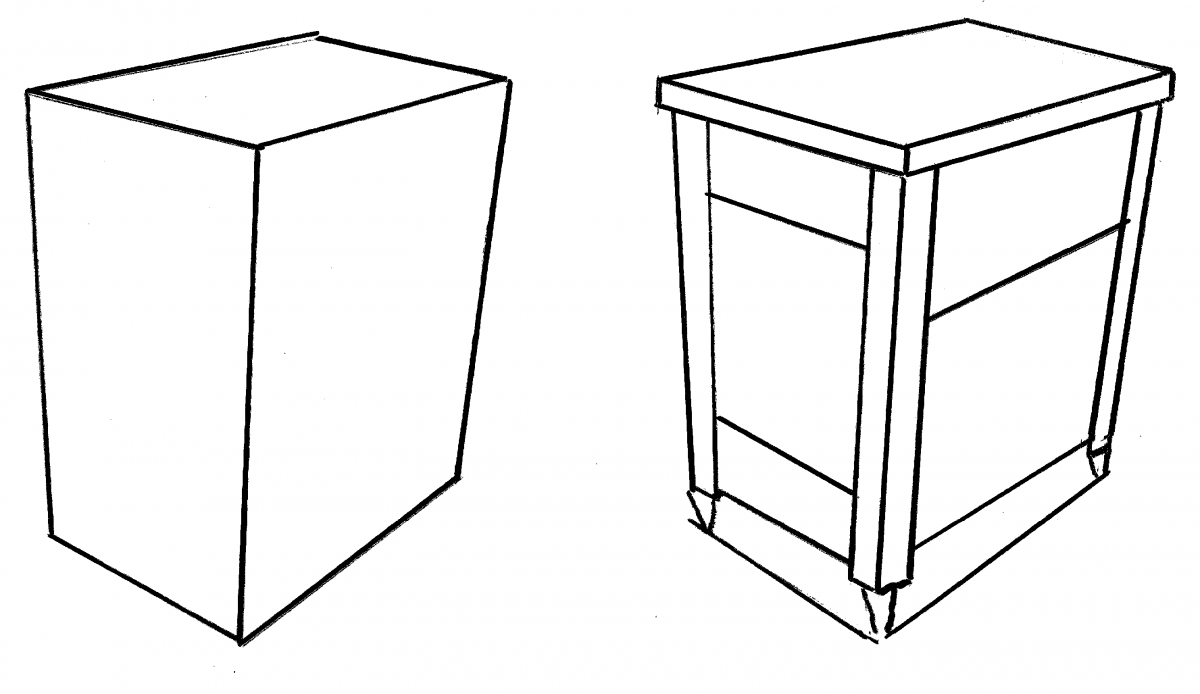

Space out. Add perspective and depth to your imagination through the exploration of space.

Lines and simple shapes include points, lines and simple shapes that can be generated with a straightedge and compass using simple geometry. They are the structure underlying any design and the building blocks of spatial organization.

Drawing is a visualization skill that can help flesh out a design. It includes quick freehand concept drawing, proportional field studies (drawing examples from real life or masterworks at a museum), simple geometric plan and elevation (façade) drawings and isometric drawings.

Space is the ability to visualize shapes in three dimensions. It is one of the most challenging skills to develop.

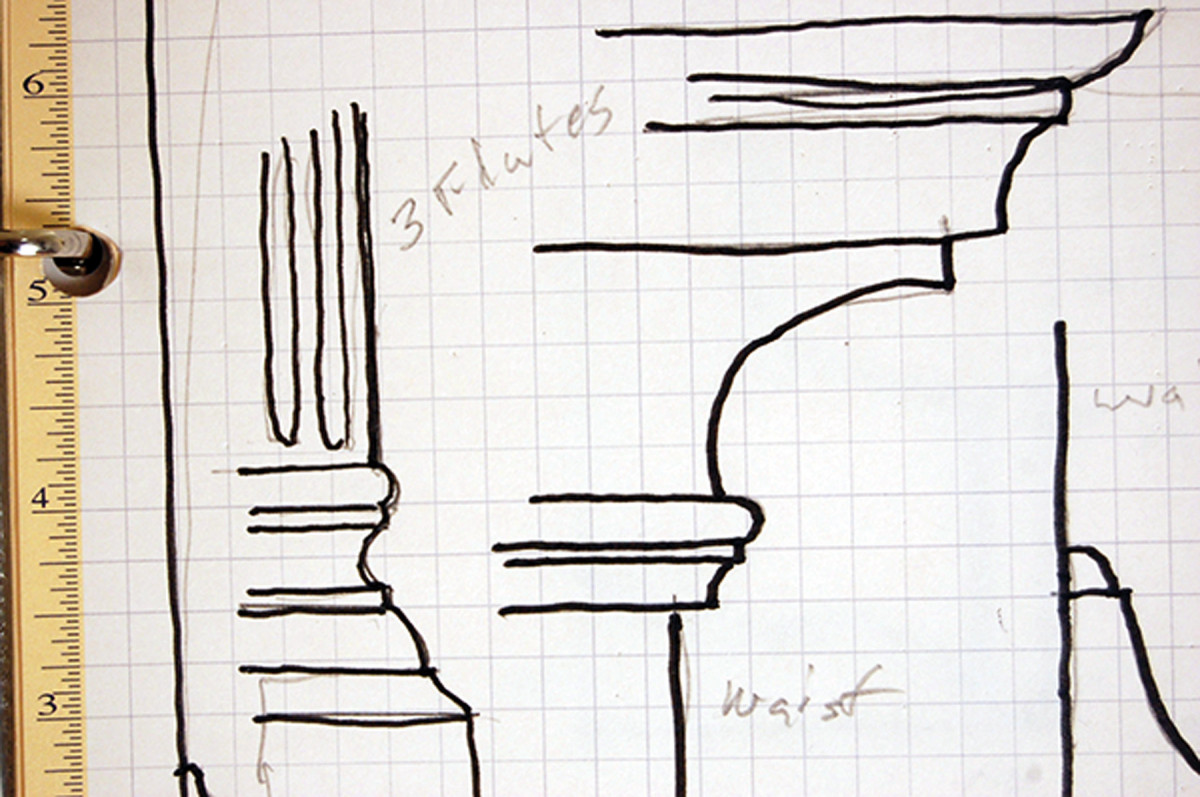

Curves refers to the ability to execute designs with sweet, natural curves.

Forms involves the combination of simple shapes, lines, solids and curves into pleasing compositions.

Practice Exercise

That fair curve. We all want to make alluring curves.

Be deliberate about practice – set aside a regular time to focus on one aspect of a core skill. Practice is a short period of time meant to address a weakness – and that’s it. It’s separate from executing a project; you won’t produce a finished product, but you need to make it part of your routine. If you have the luxury of a full day in the shop, give yourself 20 minutes to practice an area in which you wish to see improvement. If time is limited, it’s still wise (perhaps more so) to schedule a regular practice session.

One practice habit that I never outgrow is visiting a museum or historic furniture collection for a period of field drawing.

Whether it’s a high-style 18th-century masterpiece, a Greene and Greene architectural detail or a nice regional piece, just sketch something that catches your eye. Field studies really amp up your observation skills and can reveal details and secrets you might never notice in a photo.

Field trip. A field study lets you look right over the masters’ shoulders and see the work through their eyes.

You can use your pencil in an outstretched arm to pick off proportions using the method I covered in the February 2012 issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine (#195) to get a lifelike proportional sketch. Just be sure to ask permission before sitting down to render your drawing (but I’ve yet to have a museum refuse me, especially when they understand that I see their collection as an inspirational resource).

I’ve summarized several of these core design skills with a single sentence, but don’t let that fool you. Each of these areas contains depths that you can explore for a lifetime!

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.