We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Though dragging your plane backward on the return stroke can make your iron dull faster, not all the old books agree that you should avoid the practice.

In fact, many of my books are silent on the issue. “Spons’ Mechanics’ Own Book,” a massive tome on woodworking and other trades, has nothing (at least that I can find) on the topic. Likewise, “How to Work with Tools and Wood,” which was published by Stanley Tools, is also silent.

But other books and authors do weigh in on the topic.

“Carpenter’s Tools” by H. H. Siegele (1950) has the most colorful explanation I could dig up:

Bringing the Plane Back.–Early in the author’s experience as a carpenter, the foreman put him to jointing board. After a while the foreman happened along, and remarked with a grin, “I notice you sharpen your plane on the return trip.” Then he went on to explain that if the tool is pulled back over the edge of the board, the heel of the plane should be lifted, otherwise the return trip would dull the plane bit, rather than sharpen it.

That short paragraph seems to settle the issue. But other authors have more to say. Charles Holtzapffel’s classic “Construction, Action and Application of Cutting Tools” (1875) has this to say:

During the return stroke, the (downward) pressure should be discontinued to avoid friction on the edge, which would be thereby rounded, and there is just an approximation to lifting the heel of the plane off the work; or in short pieces it is entirely lifted.

Holtzapffel’s description is exactly what I do. I pull the tool back by the tote with no downward pressure at all.

But then there is “Audels Carpenters and Builders Guide” (I have the 1947 edition), a four-volume set of books on the trade. In Vol. I in the section on “Smooth Facing Tools,” the authors make the following dictum:

In planing on the return stroke lift the back of the plane somewhat so that the cutter will not rub against the wood and thus prevent it being quickly dulled.

This refers to large surfaces especially when they are rough, but on small work it is not necessary.

This seems to directly contradict Holtzapffel. So I went to the mountain: Charles H. Hayward, my personal woodworking hero. I didn’t go through all his writings on planes – that would take a few days. But I did consult his seminal “Tools for Woodwork” (1973). His advice is nuanced.

It will probably not prove practicable to take the plane right through the length of the wood (when smoothing). The best plane therefore is to raise the right hand as the far end of the stroke is reached so that the plane ceases to cut. Do not attempt to lift the plane bodily as this will invariably leave a mark.

Hayward is suggesting that the worker release the downward pressure on the return stroke when smoothing, much like Holtzapffel.

So I think that all the sources would agree that you shouldn’t bear down on the tool during the return stroke, which is like saying, “Duh, you should not poop in the water you drink.”

However, they don’t agree on if you should pull back while lifting the heel of the tool or merely release the downward pressure.

To me, this says I should dig deeper into the issue and start combing through all my books. Or just go back to building stuff.

— Christopher Schwarz

For a discussion of when I drag (and don’t) check out this story I wrote earlier today.

Also, don’t forget to check out my new DVD called “Super-tune a Handplane,” which shows you how to turn an old plane into a high-performance tool. You can get it at ShopWoodworking.com.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

The issue at hand here is whether dragging the tool is detrimental to the cutting edge. I have used hand tools exclusively to build many pieces of furniture. I don’t do this for clients as they cannot afford furniture build using only hand tools, so most of these pieces are mine. Upon recollection, I remember many hours spent at the sharpening stones. Returning chisels, scrapers,plane blades and the like to a proper razor mirror edge.

If dragging a plane bothers you, mentally, then don’t do it. The rocking nature of man planing wood is more than enough kinetic energy to lift the sole off your work, as dragging any part of the sole across your stock is only for scrub planing IMHO. I prefer to put my time, thought and energy into sharpening, which never can be avoided. This is an typical academic topic that could easily be replaced with, for example: how to execute fox wedging.

Something to consider…for discussion sake: Cabinetmakers, Joiners, and Carpenters of the hand work era were much different than we hobbyists and even professionals of today. Our woodworking forefathers were conditioned, and even bred, over generations to have physical endurance that we just don’t have today. Those men spent long hours, day in and day out, week after week, month after month, year after year, laboring physically in ways that some of us, at most, do for an hour or two at a time. We then get weary, and leave our shops to go sit in our Lazyboy recliner and watch a DVD to try to figure out the method that was used to keep from tiring while planing a board. I’m not trying to offend anyone by minimizing thier physical abilities, nor am I saying that dragging a plane is right or wrong, was done or wasn’t done. I once aquired a tool chest full of carpenter’s tool including a jack plane that is shaped like a wedge from wear at the toe, suggesting that the user may have lifted the heel on the backstroke. He also may have just applied greater pressure to the toe on the forward stroke, its hard to say. I think studying old tools is a good way to look for answers as to how they were used, but sometimes the use varied by user, and by time period and trade. The plane I spoke about was used by a carpenter in the mid to late 19th century.

I also think this is a great discussion helpful to those of us trying to learn, understand, and duplicate the methods of those who came before us. Thanks Chris!

The deceased woodworkers before us have told us how they used their planes. One just has to look at antique planes. Hundreds of wood and metal planes have passed thru my hands; after all, I am a collector as well as a user.

A well worn wooden or metal plane will be worn at the heel and toe when checked with a straightedge. Wear on the toe indicates that the plane may have been lifted and “dragged” back to the starting point, and or it met the wood in an arc to begin the pass, like a plane landing.

Wear on the heel says the plane was lifted from the wood at the end of a pass, like a plane taking off.

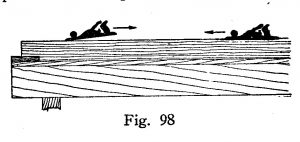

Another way to bring a bench plane back is to simply tilt it a bit. You don’t lose contact with the wood and the blade doesn’t drag. Frank Klaus does it this way. I use heavy infilled planes, and this method works well. It would wear me out to lift them completely off the wood for each pass.

You can tell if the workman used this method when the edges of the plane are chamfered. This must be done or the sharp edges will dig into the wood. The premium apple wood and rosewood wooden planes that the Sandusky Tool Co. sold came ready to use with a heavy chamfer already done for the user.

Antique molding planes also will be worn at the toe and heel due to lifting the body off the wood enough to avoid dulling the iron, but not so as to lose contact with the wood.

The old guys were concerned with doing a good job as efficiently as possible as most were paid by piece work. Their methods of planning wood achieved that. Today, we are more concerned with keeping the plane bottoms flat.

Hey Chris,

It depends.

I agree with you that for tough work with a jack plane, or especially with a scrub plane, I drag the plane back even if it is detrimental to the edge. Resharpening beats constant lifting. For a smoother, yea, I want to preserve the nice edge as much as possible, so no dragging there.

Depends on the wood too!

But I think we should also distinguish what is happening with bevel-down vs bevel-up planes. The extra wear on the BD blade is much more easily removed than the “wear bevel” on the flat (down) side of a BU blade. So I’d avoid dragging BU planes, UNLESS the “ruler trick” is used for sharpening the BU blades. This is one reason I converted to using the ruler trick on my BU blades.

And it depends on my body mechanics. Reaching across a wide board and lifting the jack plane when working with cross-grain strokes can be a back breaker.

As usual, it depends . . .

Thanks for a good, practical discussion topic.

Rob

Last night I watched a DVD by Jim Kingshott and noticed that when planing shorter boards he made no effort to lift his plane on the return stroke. When planing a long board KIngshott would take a full length stroke, walking as needed. Then he would lift and carry the plane back for the next stroke.

Jim Kingshott died in 2002 at age 70 so he qualifies as deceased. He had previously been the mast of apprentice cabinetmakers for the Royal Air Force.

I can’t see how dragging the plane back across the board helps any. Maybe it doesn’t hurt, maybe it’s more efficient, but I can’t see how it will make the board plane any better.

Could this be one of those things which many believe is a truth, but it’s never been tested to see if it’s so? I think the only way to find out is to do a comparison test. How it could be done, I don’t know yet, but can you imagine how much planing effort – and time – could be saved if it could be proved that the dulling action of dragging is insignificant? Or how much sharpening effort and time could be saved if it turns out to be significant? What if it actually does sharpen the blade? Counter-intuitive I know, but what if it’s true? The only way to settle the matter is a “Mythbusters” style of test. If anyone can be bothered.

Does this issue change while using a plane on its side with a shooting board? This would make the back stroke very awkward.

I say quit “dragging your heels” and build something. Although it would make an interesting article someday once you have your research completed.

Keep up the good work!

If you watch Paul Sellers planing on his videos, his first pass forward sets the distance his arms will travel. He’ll even move his upper body back so his left arm can only reach as far as he intends to plane. On subsequent passes, just as his left arm is almost completely extended, he lifts the back of the plane with his right hand. He’s been doing this for a very long time and I suspect that he was taught the method Hayward mentions. This technique is quite evident in many of his videos with planing in them if anyone would like to see it demonstrated.

Taken by itself like this, it sounds to me like Hayward is talking about planing a long board in sections at a time instead of walking along the whole length to take a full length shaving. Is there more around the paragraph to imply that he is talking about the return stroke?