|

Walk into a typical small cabinet

shop, and you’re likely to find

simple, functional cabinets made of

inexpensive sheet goods. Not that these

pros couldn’t make furniture-grade

cabinets for their shop if they wanted,

but when there are customers waiting

and bills to pay, shop cabinets get built

fast, cheap and solid.

These cabinets are right out of this

tradition. They’re fast to build, so you

can move on to building real furniture

for your home. They’re sturdy and

flexible, so you can adapt them to all

sorts of storage needs, even heavy tools

and hardware. And best of all, they’re

cheap.

All the material and hardware should

be available at your local home center.

Multi-purpose cabinets

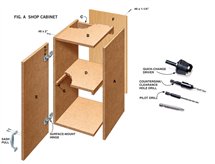

These basic cabinets can be used on

the wall, on the floor, on wheels, backto-

back—any way you want. As you

can see, we used them as the foundation

for several basic pieces of shop furniture.

The drawers range in size from

a bit more than 1-in. deep, for small

tools, to almost 6-in. deep for heavy

stuff. The drawer design is so simple

you can easily modify the dimensions

and customize the sizes.

You can also use these cabinets as

outfeed support for your tablesaw.

With a 3/4-in. top and casters or a

base underneath, the total height of the

cabinet will be 34 in., a common height

for tablesaws.

Materials

We made our cabinets out of

medium-density fiberboard (MDF)

because it’s strong and inexpensive.

MDF paints like a dream, but you

could also use a clear finish or no

finish at all on these cabinets.

Although MDF comes in 49-in.

x 97-in. sheets, the cabinets are

designed so you could also use fir or

birch plywood in normal 4×8 sheets

without changing any dimensions.

MDF is not a perfect material,

however. It’s heavy, for one thing,

so get help if you’re going to install

these cabinets on a wall. Attach

them very securely to studs using

3-in. drywall screws. The drawer

unit should not be hung from a wall

at all. It’s simply too heavy.

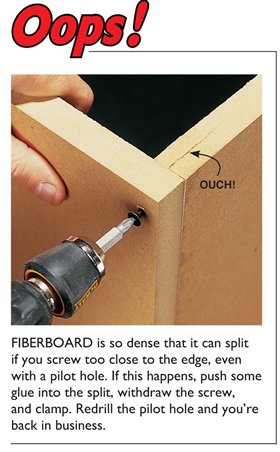

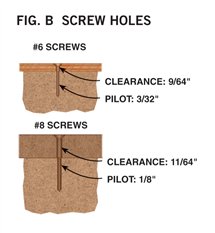

The other drawback to MDF

is that it only holds screws well

when they are correctly installed.

The screws can’t be too close to an

edge, or they’ll split the material (see

Oops!, at right). You must drill good

pilot and clearance holes (Fig. B) or

the screws will snap or fail to hold.

And finally, coarse-thread utility or

deck screws will hold better than

fine-thread drywall screws.

Oops!

Modifying the design

We have designed these cabinets

so you get the most number

of cabinets from the least amount

of material. However, it is easy to

modify the dimensions to suit your

needs. You can put more shelves in

the cabinets, more drawers in the

drawer unit, or turn the drawers

into trays. Don’t make the cabinets

more than about 32-in. wide, however,

because MDF sags under its

own weight.

You may want to use a different

material altogether. You could go

upscale by choosing birch plywood

with solid-wood edging. Or make the

cabinets white and easy to clean with

melamine-covered particleboard.

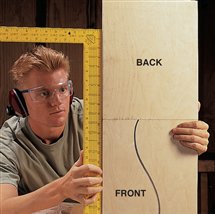

Tools and supplies

We’ve come up with a building

process for these cabinets that

makes handling the sheet material

as easy as possible. The first step,

whether you’re making one cabinet

or a dozen, with drawers or without,

is to rip each full sheet into

three long pieces (see Cutting Diagrams, below) These more manageable

pieces can then be crosscut and

ripped narrower, as needed.

An easy way to crosscut sheet

material accurately is with a crosscut

sled on your tablesaw. You can

build a full-featured sled, but we’ve

included a simpler design here that’ll

work just fine.

In the tool department, very little

is required. You’ll need a tablesaw,

a drill, four 18-in. capacity clamps

and a quick-change driver/countersink

attachment for your drill

(Photo 3). In addition, because MDF

is extremely dusty stuff to cut, we

strongly recommend wearing a good

dust mask and having a dust collector

on your saw.

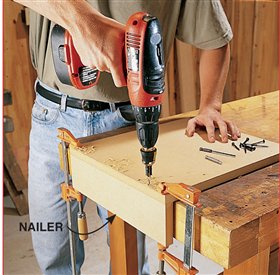

This is the kind of project where

air tools excel, so if you can get your

hands on them, you’ll save a lot of

time. A brad nailer speeds up building

the drawer boxes (Photo 8), and

can eliminate clamps during assembly

of the cabinets (Photo 4). A narrow

crown stapler does a fast and

effective job of holding the backs on

the cabinets and the bottoms on the

drawers.

Construction overview

The first thing to consider is how

many and what type of cabinets

you want. We suggest you build the

basic shop cabinets in multiples of

four or eight. This makes the most

efficient use of your materials (see

Cutting Diagrams).

The drawer units are best made

in multiples of two. You’ll be able to

make seven drawers in each cabinet

with only one sheet of 1/4-in. plywood.

If you’re only building four

of the basic cabinets, there will be

plenty of 1/4-in. plywood left over

for additional drawers, but if you’re

building eight, you’ll have to buy

more. No matter how many drawers

you make, one sheet of 1/2-in. plywood

is plenty for two cabinets full

of drawers, and a crosscut sled.

Building the cabinets

If you’re going to build the simple

crosscut sled at right, the first

thing to do is rip your 1/2-in. plywood

into three strips: two 14-3/4-

in. wide and one at 18-in. wide.

Crosscut the 18-in. strip using a

circular saw, a jig saw or a tablesaw.

Then proceed with the building

steps for the simple crosscut sled

given at right.

The basic building steps for the

cabinets are shown in Photos 3

through 11. Begin by ripping your

MDF into 15-1/2-in.-wide strips.

Then crosscut to give you the sides

(A), the doors (E) and the tops and

bottoms (B). Rip the shelves (D)

to width and cut the nailers and

cleats out of the remaining material.

Check all the parts to be sure

they’re square and that all parts of

a given size are within 1/16-in. of

each other.

The cabinet assembly process is

pretty fail-safe, because you clamp

the pieces together first to get all the

edges lined up, and no glue is used.

Even after you’ve screwed pieces together, they can be taken apart and redone if you’ve made

a mistake.

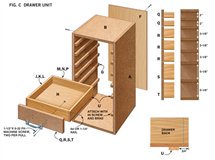

Building the drawer units

The drawer units start with a case that’s the same as the

basic cabinet, except it doesn’t have a door, shelf or nailer.

With the cabinet boxes made, install the cleats that support the drawers (Photo 7). Build the drawer boxes next. Use

glue on all the joints, because the nails aren’t enough on

their own. Attach the drawer fronts (Photo 10), the pulls

(Photo 11) and that’s it.

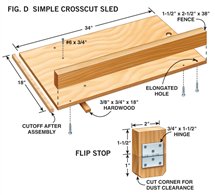

A Simple Crosscut Sled

This sled makes it much easier to accurately cut large pieces

of sheet stock and pieces that are too wide and awkward

for your miter gauge. With only three pieces, it shouldn’t

take you more than an hour or so to build. We’ve included a

simple stop, which makes it much easier to cut multiple parts

to the same length.

Begin by cutting out the three pieces for the sled. Make

sure the strip that goes into your miter gauge slot has a snugsliding

fit. Screw the strip to the sled so the sled overhangs

the tablesaw blade by about 1 in. and is square to the back

edge of the sled. Attach the fence so it’s also square to the

back edge of the sled. Screw the fence through the elongated

slot, so it has a little adjustability. Run the sled through the

saw to trim it even with the saw blade (Photo 1, below). Test cut a

12 to 16-in.-wide piece of plywood (Photo 2, below) and check the

cut for square. Adjust the fence position until your cut is

perfectly square. Fasten the fence permanently with a couple

more screws.

The stop can be flipped out of the way for the first cut on

a board, then flipped down and used for the final cut.

1. Build the sled wide enough so that your

first cut trims off the end of the sled. That

way, the end of the sled will line up perfectly

with the blade.

2. Test for a perfect cut by

cutting a wide piece of plywood,

flipping one half over, and butting the

pieces together. The edges should be

perfectly straight.

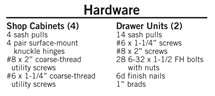

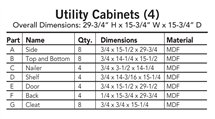

Hardware

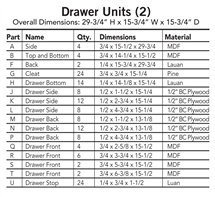

Utility Cabinets (4)

Drawer Units (2)

Cutting Diagrams

Fig. A: Shop Cabinet

Fig. B: Screw Holes

Fig. C: Drawer Unit

Fig. D: Simple Crosscut Sled

This story originally appeared in American Woodworker June 2001, issue #87.

|

|

Click any image to view a larger version.

Rolling shop carts are

always handy. This one uses two

cabinets, and is the same height as

our tablesaw. You could also use

four or six cabinets for a larger

rolling assembly table or an outfeed

table.

A rolling tool chest is

made from two drawer units, with a

top and casters. Because this chest

will carry a lot of weight, reinforce

the bottom with braces.

Support a workbench

with two or three

cabinets. This bench has a

plinth to raise the cabinets

up off the floor, and a top of

MDF edged with hardwood.

A wide cabinet is easily

made from one of the basic

cabinets. Flip the cabinet sideways,

cut a new, longer nailer, and use

double doors in front.

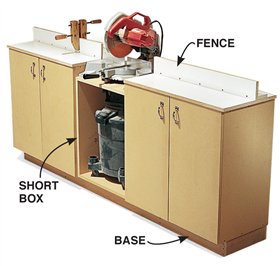

A miter saw stand is built from

four or six cabinets with a shorter box in

the middle to support the saw. A narrower

base ties all the units together and provides

a toe space.

Make extras for the laundry room,

garage, or wherever you need utility storage.

1. Rip the sheet material first,

to get it to a manageable size. The

MDF is heavy and produces tons of

fine dust when cut, so have a helper

and some dust control handy.

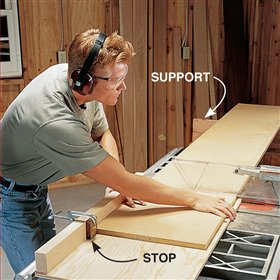

2. Crosscut the strips of MDF.

A simple shop-made sled makes it

easier to get accurate cuts on these

large pieces, although you’ll need to

support the far end. A hinged stop

on the sled allows you to flip the

stop up for the first cut, then flip it

down for the final cut. The result:

every piece is accurate and identical.

3. Join the top and the nailer with utility (drywall-type)

screws and no glue. Clamp

the pieces to get the alignment

perfect, then drill the pilot hole

and countersink. A quick-change

unit and combination bit makes

this operation go quickly.

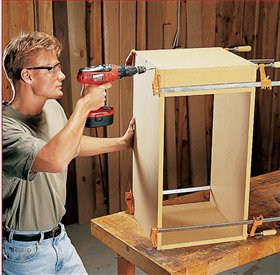

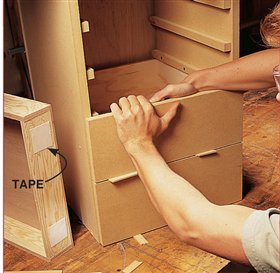

4. Join the rest of the box the

same way, using clamps to get parts

aligned. These joints are plenty

strong with just screws, so no messy

glue cleanup is required. Plus, if you

ever want to modify the cabinet, it

will come apart neatly.

5. Attach cleats for the shelves, using a piece of scrap

to align them. This may not be the

prettiest shelf support in the world,

but it’s strong, cheap and completely

adjustable.

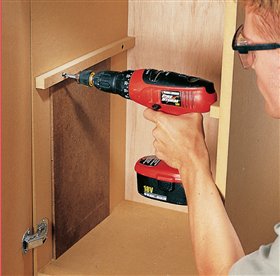

6. Hang the door from inside the

cabinet. This is a pretty weird-looking

way to do it, but it works great!

Simply attach the hinges to the door,

then clamp the door to the cabinet

box so it’s aligned all the way

around, and then screw the hinges

to the inside of the cabinet. Finally,

screw on the back of the cabinet.

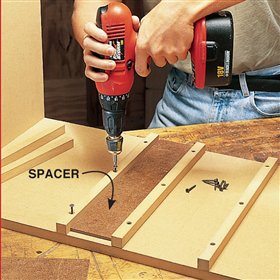

7. Attach drawer cleats, using

a spacer to get them square and the

same distance from the bottom of

the side. Start at the bottom, and as

you move up the side, rip the spacer

to a narrower width, as needed.

8. Drawer boxes are made from

1/2-in. plywood, held together with

nails and glue. You can simply hammer

them in, but a brad nailer makes

this part of the project go much

faster. The 1/4-in. plywood bottom

is glued and nailed directly to the

bottom of the drawer.

9. Drawer stops, one on the

drawer and one on the cleat, prevent

the drawers from falling onto

your toes if they’re pulled out all the

way. Remove the front stops if you

prefer to be able to pull the drawer

out to use as a tray.

10. Attach the drawer fronts

to the drawer boxes while they’re in

the cabinet. Use double-faced tape

to hold each front in place, once you

have it perfectly aligned.

11. Bolt on the pulls so they hold

the drawer front to the drawer box

securely. Center each handle on the

drawer front.

Tip: Paint before you assemble. If you want to paint your cabinets, save yourself

some work by painting the parts before assembly.

The paint might get a little scuffed while you’re

building, but all it’ll need is a final coat and some

work on the screw holes.

|