We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Once the hood was removed, the clock’s brass movement was revealed. The relatively bright finish and minimal oxidation on many brass surfaces reflect both the long-term environmental stability where the clock was kept and the fact that brass movements were originally finished to shine and often protected with a coating. In conservation practice, a lightly aged brass surface is not surprising for a well-kept clock of this period and may be preferable to over-polished parts, which can erase historical surface character.

If part one focused on the cabinet as an archaeological object—revealing construction shortcuts, repairs, and surprises—this second part turns inward, to the heart of Yeoman’s clock: the movement itself. It is here that the clock most clearly declares its origin, quality, and historical standing.

The Movement

Once the hood was removed, the movement could be examined in situ and then more closely. It is a substantial brass longcase movement of clear London manufacture, built on heavy plates and showing the confident layout and finish expected from a professional metropolitan workshop of the late eighteenth century.

The train layout, plate proportions, and general execution indicate a time-and-strike movement of good quality rather than a provincial or purely utilitarian build. Wear patterns are consistent with long service but not abuse, suggesting a clock that was maintained and valued rather than neglected. The overall impression is of a movement designed to be reliable, serviceable, and enduring.

One particularly important feature is the strike/silent dial in the arch. This complication allowed the owner to silence the striking mechanism at will—a refinement that speaks to both domestic comfort and social expectation. Its presence places the clock firmly in a higher tier of domestic longcase clocks and aligns it with London tastes rather than rural necessity.

The Maker: Francis Perigal, London

The movement is signed Francis Perigal, London, a name well known to horological historians. Francis Perigal was not an isolated craftsman but part of a multigenerational family of clockmakers active in London from the mid-eighteenth century into the early nineteenth century.

Several members of the Perigal family—commonly distinguished in records as Francis Perigal I, II, and III—were freemen of the Clockmakers’ Company and worked in succession, maintaining workshop continuity at the Royal Exchange and nearby addresses. Together, they produced longcase clock movements, bracket and table clock movements, and watches. The consistency seen across signed Perigal work reflects an established London workshop tradition rather than the output of a single individual working alone.

Perigal movements are generally associated with sound design, restrained ornament, and mechanical clarity. While not extravagant showpieces, they were built to meet the expectations of an urban clientele that valued reliability, legibility, and respectable refinement.

Who Made the Case? Understanding the Division of Labor

This brings us to a crucial point—one that is often misunderstood outside specialist circles: the movement and the case were almost certainly not made by the same hand.

By the period in which the Yeoman’s clock was made, London clockmaking operated through a network of specialized trades. Movement makers like the Perigal family focused on horology: wheels, pinions, escapements, and striking work. Cabinetmaking, by contrast, was typically the domain of independent joiners or cabinetmakers, either contracted directly by the clockmaker or commissioned separately by the client.

There were several common arrangements:

- A client might purchase a finished movement from a clockmaker and commission a local cabinetmaker to house it.

- A cabinetmaker might acquire a movement and build a case for resale.

- A clockmaker might maintain working relationships with one or more cabinetmakers but not employ them in-house.

What matters here is that no single model governed all production, and quality could vary independently between movement and case.

In the Yeoman’s clock, this division is palpable. The movement reflects disciplined London workmanship. The case, particularly in areas revealed only through damage and disassembly, shows more expedient construction methods—some surprisingly so. This contrast does not diminish the clock’s historical interest; rather, it enriches it by showing how objects like this were truly made and assembled.

Significance and Rarity

The significance of the Yeoman’s clock lies not in extravagance but in authenticity. It is a genuine London longcase clock with a signed movement by a respected maker, incorporating desirable features such as the strike/silent control. It has not been over-restored, modernized, or homogenized to meet contemporary tastes.

Equally important, it preserves evidence—sometimes uncomfortable evidence—of period construction practices. The survival of glue-only joints in parts of the hood, reinforced with scrap molding rather than formal joinery, tells us as much about eighteenth-century workshop economy as any polished surface does.

A Note on Value

From a market perspective, clocks of this type occupy a middle ground that is often overlooked. A London-signed Perigal longcase clock, with original movement and period case, carries clear historical and monetary value, though it does not reach the heights of rare musical clocks or highly ornate bracket clocks.

Condition, originality, and the quality of any future restoration will significantly influence value. Over-restoration—especially alterations that erase construction evidence—can reduce both scholarly and financial worth. As it stands, Yeoman’s clock derives value not only from who made it, but from how honestly it has survived.

Looking Ahead

This examination sets the stage for the final and most consequential discussion: what to do next. Any course of action—conservation, restoration, or stabilization—must balance mechanical function, historical integrity, and the intentions of the owner.

That conversation belongs in Part Three.

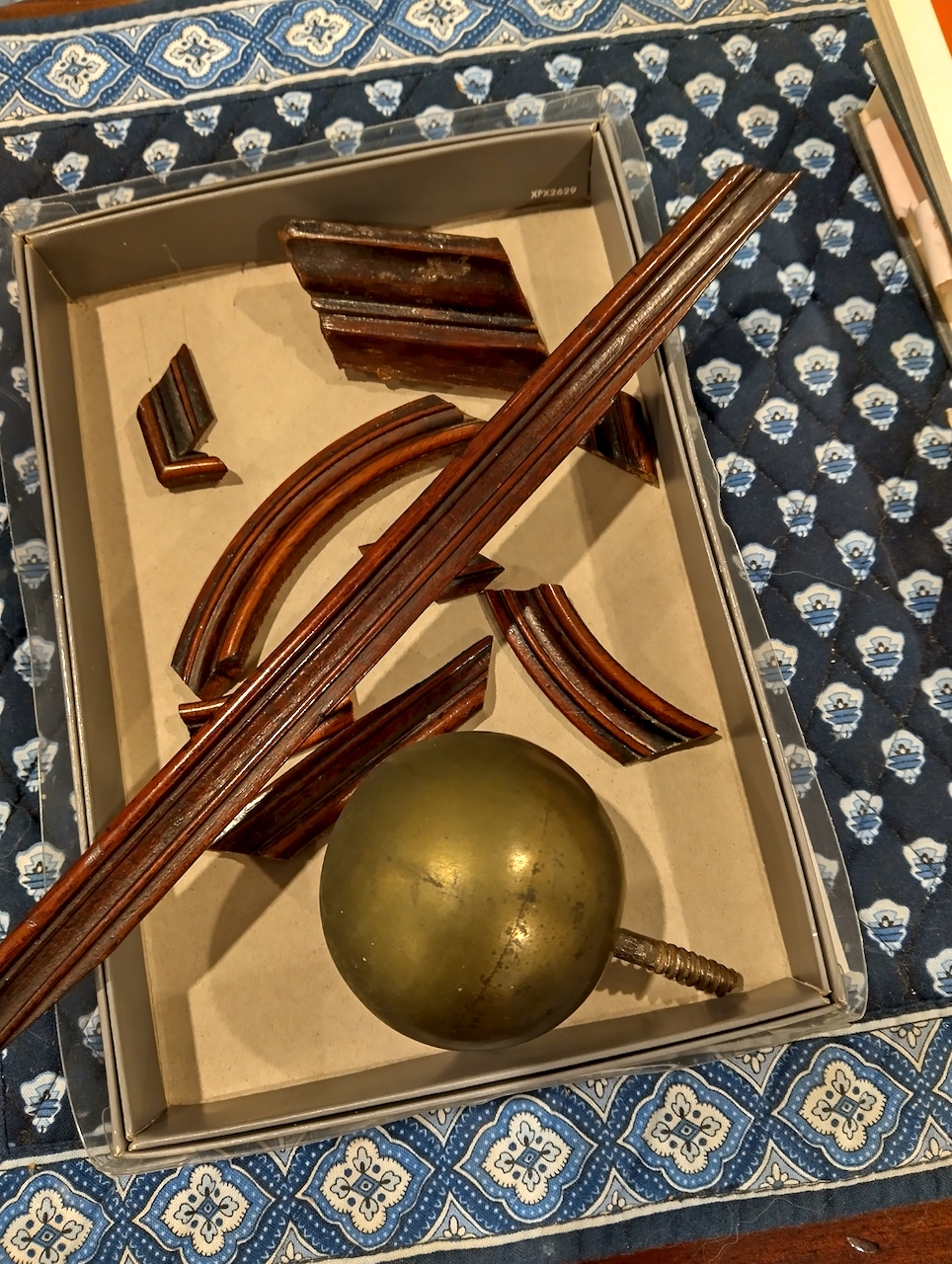

A box of components that had detached from the clock and were carefully kept by Kay. The mahogany moldings and brass finial ball will be reattached during restoration. Only a small number of replacement parts will need to be made from scratch.