We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

The best work is often built one piece at a time, so toss your cutlist.

The best work is often built one piece at a time, so toss your cutlist.

I have been in professional piano repair and tuning for more than 30 years. My father taught me how to tune by ear. That’s “old-school” style.

The piano is an imperfect instrument. When a note is played, a series of imperfect harmonics are produced in the string. In the tuning process the ear and brain immediately calculate how much to “temper” each note so it is acceptable with other imperfect notes. Using this method of comparing frequencies tells you exactly how to best tune a piano.

This tempering is the aural equivalent of sfumato, a painting technique in which lines are blurred – Leonardo da Vinci used this technique when painting the Mona Lisa. Many consider it to be a masterpiece; however, a person might argue that work from a paint-by-numbers set is the perfect painting with its predetermined colors placed perfectly between the lines.

Similarly, an electronic tuning device measures the fundamental frequency and a harmonic of one note, then calculates a value that is then used to place all the notes inside the lines.

The difference between a properly done aural tuning and a tuning using an electronic device, in a nutshell, is akin to the difference between a painting by da Vinci and that from a paint-by-numbers kit.

So what does this have to do with woodworking? Piano builders back in the day were rarely restricted by measurements. They had a few critical numbers to get them going for a particular model, but old documents and plans are lacking in dimensions. These craftsmen didn’t need or use many measurements, yet old instruments are some of the best ever made.

Truly crafted by hand, old pianos were assembled piece by piece with each step trued up using the proper hand tool. The dimension of the next part could not be known until the previous step was completed. Indeed, period makers didn’t care what the size was – they would simply glue on the next part then plane it to a perfect fit. This process also avoided introducing external stresses that come when one tries to force a “perfectly” pre-dimensioned part into place during assembly.

Modern day mass-production techniques require that all the parts be machined to exact tolerances before assembly. It’s impressive how good some of the better mass-produced pianos are, but the truly great instruments are still built by hand.

I recently was commissioned to build a bookcase in which the starting dimensions were determined by the size of the boards. My client wanted the bookcase to be 9′ feet long with no one piece longer than 36″. And it had to able to be disassembled.

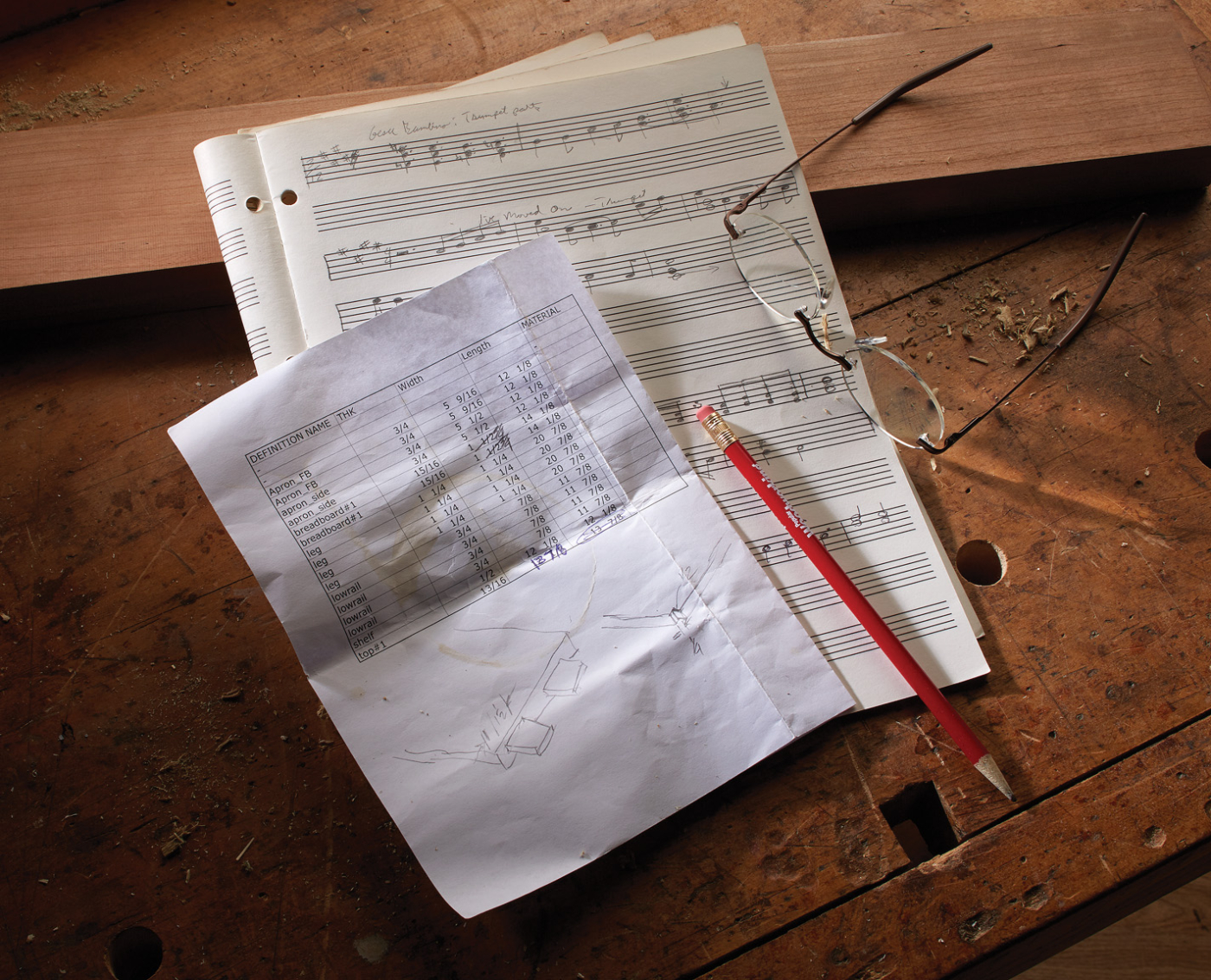

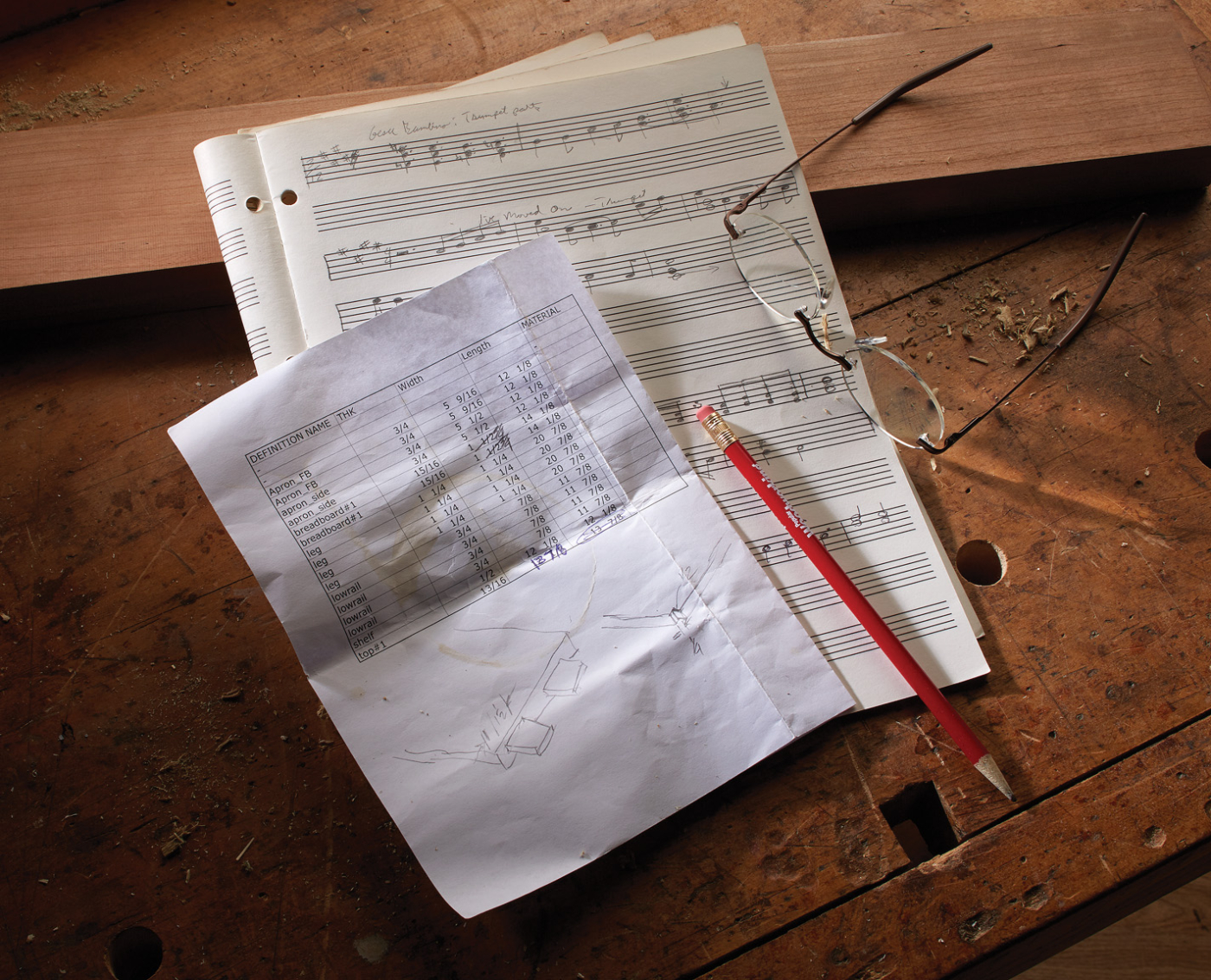

To have fun with the design, I decided to make it fit together like a puzzle. I would use no glue, no screws, no tape measure and no plans; I would, however, use a story stick.

I designed the bookcase with sliding dovetails and an interlocking top that was slightly oversized to spread the sides and put pressure on the dovetails.

With the sides spread 1⁄4” out of square, the two outside back slats were cut accordingly. The center back piece had beveled edges and fit like a keystone to lock the carcase tight and square. It was one of the most enjoyable projects I’d done in many years.

So the point is this: When you are woodworking, are you painting by numbers or making a true work of art? Do you assemble pieces sized from a cutlist, or do you “tune by ear?” -Glen Hart

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

The best work is often built one piece at a time, so toss your cutlist.

The best work is often built one piece at a time, so toss your cutlist.