We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Stickley’s #210 settee embodies Arts & Crafts simplicity, honesty, and craft in one iconic design.

A hundred years ago, Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops were busy producing some of the most exceptional furniture of 20th century America. This interests me because, for years I described, through measured drawings, hundreds of pieces of furniture. I illustrated several books and articles for my brother (Kerry Pierce) that were published through Popular Woodworking. Many of the later projects provided the opportunity to examine antiques in museums. Prior to those visits, I’d only drawn antique replicas and other, more modern pieces.

The first museum I visited was in the Shaker Village at Pleasant Hill in Kentucky. Many of the pieces previously drawn were Shaker inspired, but I’d never seen an original. Here, I was surrounded by original antiques, housed in original Shaker buildings, constructed nearly two hundred years earlier. I was never particularly interested in museums prior to my visit to Pleasant Hill, but working late at night in those silent rooms, I felt the presence of the people who once lived and worked there.

I’ve measured a number of the antiques since, and I’m always curious about the creators of these pieces. This curiosity, coupled with a fondness for furniture that is simply designed and elegantly constructed, guided me to the work of the Craftsman Workshops. Here are wonderful examples of solidly built, beautifully proportioned furniture, designed to faithfully serve its purpose, rather than act as a decoration. This type of design generally produces a more attractive piece than one intended for beauty alone.

My initial intent of this article was to explain exactly how the #210 Settle (shown below) was made with measurements and drawings I was able to make off of the original. And, that will come in a future issue. Instead, I first want to offer up some background and philosophy of the American Arts and Crafts Movement.

Stickley (and many others) held a philosophy that motivated them to attempt to create not only arts and crafts, but better lives for both the artists and their clients. The artisans would make their merchandise by hand in better working conditions than existed in the industrial environment of the time, and the consumers would receive superior products at a lower price. This proved to be as difficult then as it is now. With a little improvisation however (for instance, some very labor-intensive work was eventually done on machines), Stickley’s was a successful venture for about fifteen years. He envisioned a total and harmonious home environment and wanted to supply all the furnishings, including the homes themselves. Attempting to produce all these objects may have been a contributing factor to his eventual bankruptcy. In spite of the brief time they were in business, if you consider how much the value has increased for the items produced in the Craftsman Workshops, Stickley’s can be considered a very successful and enduring venture.

I hope that this article provides today’s craftsmen with the appreciation for the furniture that Stickley produced, and hopefully will help to inspire furniture that will be examined a hundred years from now.

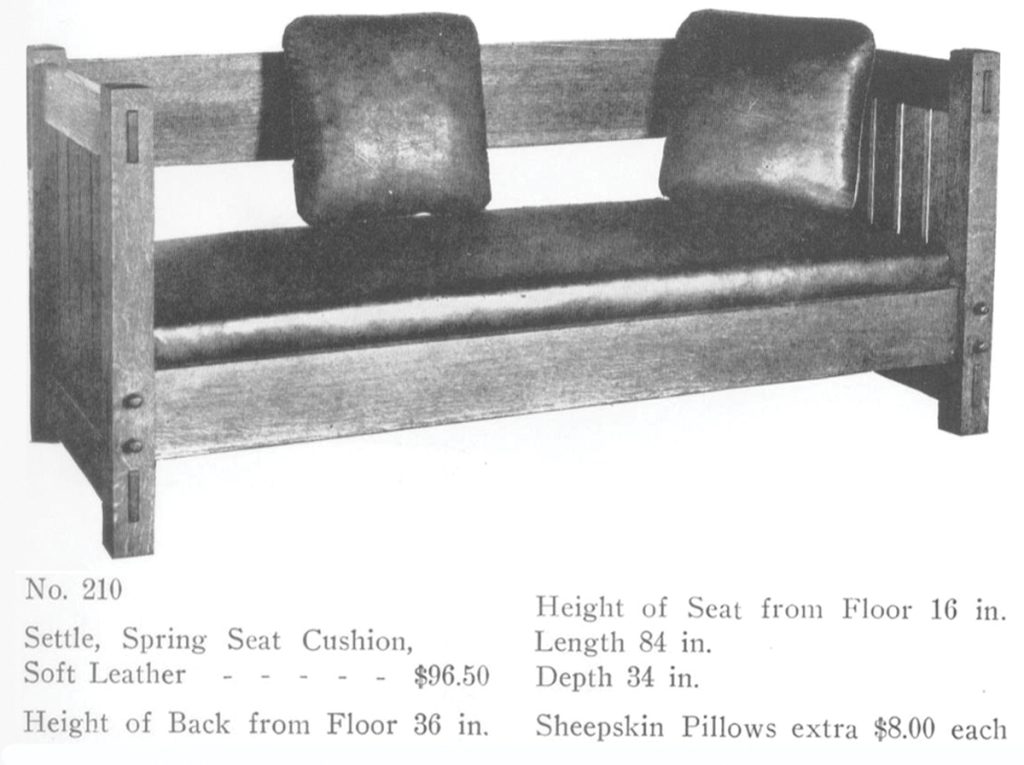

Gustav Stickley Settle #210

Gustav Stickley Settle #210

The cabinet work from the Craftsman Workshop Catalog D circa 1904 describes the Settle #210 as, “Made in Craftsman Fumed Oak. 36“ high, 84“ long, 34“ deep. Seat cushion covered in Craftsman canvas or leather. The size of the seat cushion is such that only one out of every one hundred hides is large enough to cover it. This is our largest settle, and the only piece we ship “knocked down.” It is long enough to allow the body to recline at full length. The tenons projecting through the front and back posts are pinned, and form a pleasing decoration.

In 1904 this piece was priced at $96.50 if you added the cost of the Craftsman leather. The Settle #210 in this article was found in an auction catalog which stated, “Good Gustav Stickley settle, #210, early knock-out form with 12“ horizontal board at back with three pull pins, six vertical slats to sides, replaced cane foundation in addition to the original foundation 84“ wide x 35“ deep x 37“ height, original finish, signed with Eastwood paper label, excellent condition.” The condition report included, “good original finish; wear consistent with age; from an important collection; includes original foundation and a reproduced foundation.

In 2007 the auction estimate for this piece was $20,000-$25,000. It’s sometimes difficult to understand what determines the value of antique furniture, but after examining this settle, with its fine proportions, structural precision, and beautiful oak grain; it’s easy to understand why the value of this particular piece increased, and why that trend will probably continue. In addition to its simple beauty, this piece is unique in its capacity to be “knocken down.” By removing the pull pins inserted through the legs and the tenons of the front and back rails, the sides can be separated from the rails, making the settle easier to transport.

In 2007 the auction estimate for this piece was $20,000-$25,000. It’s sometimes difficult to understand what determines the value of antique furniture, but after examining this settle, with its fine proportions, structural precision, and beautiful oak grain; it’s easy to understand why the value of this particular piece increased, and why that trend will probably continue. In addition to its simple beauty, this piece is unique in its capacity to be “knocken down.” By removing the pull pins inserted through the legs and the tenons of the front and back rails, the sides can be separated from the rails, making the settle easier to transport.

Gustav Stickley (1858-1942)

Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops in Eastwood, New York, produced what is generally believed to be the finest furniture of the American Arts and Crafts movement in the early 20th century.

Stickley’s professional furniture experience began at his uncle, Jacob Schlaeger’s, chair factory in Brandt, Pennsylvania. In 1884, with his brothers, Albert and Charles, he founded the Stickley Brothers Company in Binghamton, New York. Stickley Brothers sold and, beginning in 1886, manufactured furniture. Gustav’s other brothers Leopold and John George came to work for Stickley Brothers in 1888. Gustav left Stickley Brothers, also in 1888, to form Stickley and Simonds with Elgin A. Simonds. Stickley worked off and on with Simonds over the next ten years. In 1898, fascinated with the style and philosophy of the Arts and Crafts movement, he visited Europe and England, and returned with a desire to emulate the work being done there, particularly the work of William Morris.

Stickley’s professional furniture experience began at his uncle, Jacob Schlaeger’s, chair factory in Brandt, Pennsylvania. In 1884, with his brothers, Albert and Charles, he founded the Stickley Brothers Company in Binghamton, New York. Stickley Brothers sold and, beginning in 1886, manufactured furniture. Gustav’s other brothers Leopold and John George came to work for Stickley Brothers in 1888. Gustav left Stickley Brothers, also in 1888, to form Stickley and Simonds with Elgin A. Simonds. Stickley worked off and on with Simonds over the next ten years. In 1898, fascinated with the style and philosophy of the Arts and Crafts movement, he visited Europe and England, and returned with a desire to emulate the work being done there, particularly the work of William Morris.

“Another object which The United Crafts regard as desirable and possible of attainment is the union in one person of the designer and the workman. This principle, which was personally put in practice by Morris, extended throughout his workshops’ the Master executing with his own hands what his brain had conceived, and the apprentice following the example set before him as far as his powers permitted.” –Gustav Stickley, The Craftsman–October 1901.

In 1898, the Craftsman Shops were established, and in 1900, Craftsman furniture was introduced to the American public at the Furniture Exposition in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

“Having been for many years a furniture manufacturer, I was, of course, familiar with all the traditional styles, and in trying to make the kind of furniture which I thought was needed in our homes, I had no idea of attempting to create a new style, but merely tried to make furniture which would be simple, durable, comfortable and fitted for the place it was to occupy and the work it had to do. It seemed to me that the only way to do this was to cut loose from all tradition and to do away with all needless ornamentation, returning to plain principles of construction and applying them to the making of simple, strong, comfortable furniture, and I firmly believe that Craftsman furniture is the concrete expression of this idea”–Gustav Stickley – Catalog of Craftsman Furniture – 1910

Stickley’s brothers continued manufacturing and selling furniture under the names, L. & J.G. Stickley Company and The Stickley Brothers Company, among others. Their furniture often mimicked Gustav’s designs, leading to this comment from his 1910 Catalogue of Craftsman Furniture:

“To add to the confusion, some of the most persistent of these imitators bear the same name as myself and what is called “Stickley furniture” is frequently, through misrepresentation on the part of salesmen and others sold as ‘Craftsman furniture or just the same thing.’”

After a disappointing affiliation with the furniture distributor Tobey Company of Chicago, Stickley embarked on his own marketing campaign in the early 1900s. The Craftsman magazine began publication in October 1901 and continued through 1913. These monthly magazines were used by Stickley as a marketing tool, and as a means to communicate his philosophy. From 1901 through 1904 these magazines, the annual catalogs, and the showrooms in the Craftsman Building in Syracuse, New York were the primary promotional apparatus for advertising and selling Craftsman furniture.

Stickley met architect and designer, Harvey Ellis in the spring of 1903, and they began working together late that year. Their partnership was short-lived however, due to Ellis’ death in January of 1904. During that brief time, much of their furniture displayed inlaid copper and pewter decorations designed by Ellis. Later, after the death of Harvey Ellis, Stickley returned to designing and manufacturing plainer furniture, more in keeping with his philosophy of simplicity and functionality.

Looking at the plain lines and solid construction in a piece of Stickley furniture, I’m inclined to consider the similarities between Shaker and Stickley furniture, not in style, but in a belief in substance over style, that the primary consideration in making furniture should be usefulness and reliability, rather than appearance. A belief that, in a well-balanced design, which is suited to the purpose for which the furniture was intended, additional embellishment is unnecessary. There were certainly many philosophical differences between the Shakers and Stickley, yet both manufactured furniture that was striking, in part, because of its solid construction, utilitarian design, and lack of ornamentation. However, despite their objections to decorations not related to functionality, both added attractive (but unnecessary) design components to their furniture.

The Shakers added ornamental finials and other turnings to their chairs, and decorative moldings and beads were added to much of their casework. Stickley added projecting tenons, arched stretchers and ornamental curves to some of his furniture, and for a short time, during his partnership with Harvey Ellis, many Stickley pieces included delicate inlaid designs. Despite these, and other, usually subtle additions, simplicity and practicality were the fundamental elements of furniture design both to the Shakers and to Stickley.

In an upcoming issue, I’ll be sharing the detailed drawings I created of Gustav Stickley’s #210 settle—a piece that stands as a true expression of his Arts & Crafts ideals. With its clean lines, solid proportions, and understated elegance, the settle captures Stickley’s vision of honest, functional beauty in everyday furniture. I had the rare opportunity to take measurements and produce full drawings of this remarkable antique (along with several other Stickley pieces) thanks to the generosity and patience of the staff at the John Toomey Gallery in Oak Park, Illinois, who made their collection accessible for close study.