We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Standing in front of Kay Yeomans’s longcase clock, it is easy to see that there is no single “correct” answer. What looks like one broken object is really a web of decisions—technical, ethical, practical, and financial. Any serious restorer, and any responsible owner, must weigh risk, cost, and authenticity before choosing a course of action.

Standing in front of Kay Yeomans’s longcase clock, it is easy to see that there is no single “correct” answer. What looks like one broken object is really a web of decisions—technical, ethical, practical, and financial. Any serious restorer, and any responsible owner, must weigh risk, cost, and authenticity before choosing a course of action.

Broadly speaking, there are three possible paths forward.

Option One — Museum-Style Conservation (The Cadillac Approach)

The most conservative and academically rigorous path would be to treat this clock as a museum object rather than as a piece of household furniture. In this model, a highly trained conservator would come to Kay’s home, document the clock in detail, and carefully disassemble every component that can be safely removed.

Loose moldings, the door, the hood, weights, pendulum, and possibly even the movement itself would be individually wrapped, labeled, and packed in custom crates with vibration-damping materials. The remaining case—particularly the tall trunk and plinth—might still need to be transported as a single unit, which is a complex and risky undertaking for something this tall, fragile, and top-heavy.

Once in the conservator’s studio, work would proceed slowly and methodically:

- Old hide glue joints would be softened, scraped, and re-glued with fresh hot hide glue.

- Warped elements might be gently persuaded back into shape with controlled moisture or steam.

- Veneer would be stabilized rather than replaced wherever possible.

- The clock would be reassembled only after every joint was understood and secure.

This is the level of care one might expect at the Metropolitan Museum or the British Museum—and it comes with a corresponding price tag. Transportation alone can cost thousands of dollars, especially when specialized art handlers are required. Shop time is billed by the hour, and a project like this could easily stretch into many weeks.

The benefit is clarity and confidence: the clock would emerge structurally sound, historically respected, and professionally conserved. The drawback is cost and risk—moving a 250-year-old clock, even with professionals, is never without danger.

Option Two — Traditional Antique Shop Restoration

A second route would be to engage a reputable antique restoration shop—one that is skilled, careful, and experienced with period furniture but not necessarily operating at museum-conservation standards.

Such a shop might:

- Repair broken moldings and reattach them cleanly.

- Re-glue failed joints.

- Potentially refinish surfaces to create a more uniform appearance.

- Make the clock stable, presentable, and functional again.

This approach is usually less expensive than full conservation because the restorer works more pragmatically and less ceremonially. However, transportation costs remain, and refinishing—while visually pleasing—can reduce historical originality.

For many families, this is a reasonable middle ground. The clock becomes whole again without the expense or strict philosophy of museum conservation.

Option Three — Hybrid / On-Site Restoration (The Practical Craftsman’s Path)

The third option—perhaps the most compelling in Kay’s case—is a hybrid approach that keeps the clock largely in place while combining on-site structural work with targeted shop repairs.

Rather than moving the entire clock, a skilled local restorer would work strategically: removing what can travel safely, repairing those parts in the shop, and addressing the more integrated structural problems in Kay’s home.

Visit One: Stabilize and Disassemble Selectively

On a first visit, the restorer could:

- Remove the door (which is designed to come off the case) and take it back to the shop for careful repair of broken mahogany moldings, veneer losses, and latch alignment.

- Slide the hood forward and off the clock’s trunk—one of the advantages of this clock’s C-shaped hood design—and transport it to the shop for re-gluing failed joints and securing decorative elements.

- With the hood out of the way, begin work on the plinth (base) in place.

Here is where craft knowledge matters.

The failed miter joints at the base would not be forced open recklessly. Instead, they would be pried apart only to a reasonable limit—just enough to allow access without stressing the surrounding wood. The old, crystallized hide glue inside the joint would then be gently agitated with a scraper or coarse sandpaper, breaking up the brittle residue so fresh glue can bond properly.

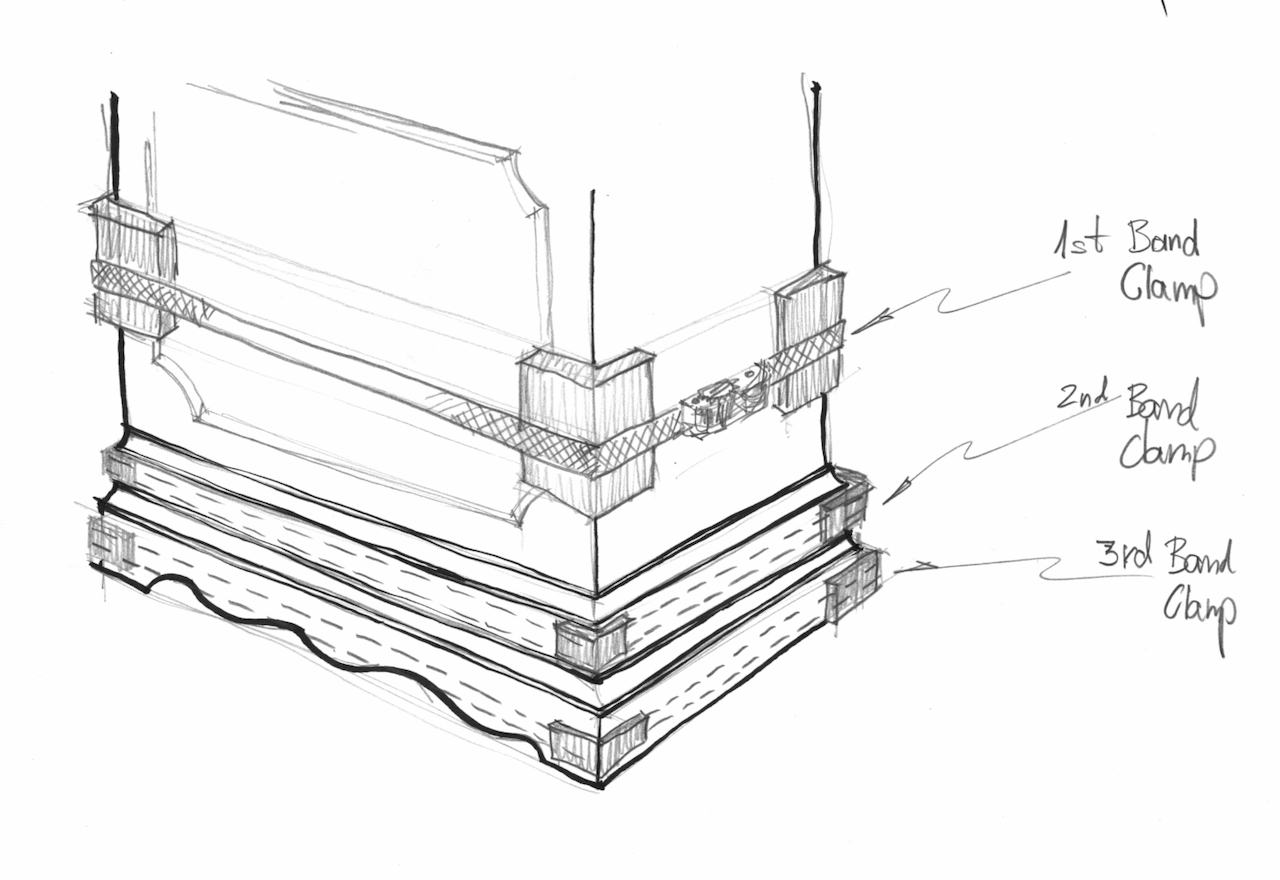

New hot hide glue would be injected deep into the joint using a syringe or narrow spatula, ensuring thorough penetration along the entire miter. The joint would then be slowly drawn closed using band clamps or strong tape. To protect the original surfaces, wax paper would be placed along the corners, and in some cases, shrink tape could be wrapped tightly around the base to maintain even pressure while the glue sets.

This method avoids dismantling the entire clock, yet still produces a structurally sound repair that respects traditional materials.

Visit Two: Reassembly and Final Structural Work

On a second visit, the restorer would return with the repaired door and hood and reinstall them on the clock.

At this stage, attention would turn to the worn latch mortise in the trunk frame, which currently prevents the door from locking—hence the red ribbon around the clock’s waist. The restorer could rebuild and extend that mortise so the latch finally has real purchase, allowing the door to close and lock properly for the first time in years.

Final adjustments would ensure that all parts sit square, stable, and visually coherent.

Why This Option Makes Sense

This hybrid method offers several advantages:

- No shipping costs and far less transportation risk.

- The most fragile decorative parts still receive careful shop treatment.

- The clock remains in its historic home, preserving context and continuity.

- The work can be phased over time, making it more financially manageable for the owner.

While this path may not deliver a pristine, fully refinished museum object, it would produce a clock that is structurally secure, visually unified, and far less vulnerable to future damage.

Closing Thoughts

Every historic object carries both history and uncertainty. With Kay’s clock, the question is not simply how to fix it, but how to honor it—balancing authenticity, practicality, and cost.

Whatever path Kay ultimately chooses, the clock itself has already done something valuable: it has opened a conversation about craft, preservation, and responsibility that many of us in the woodworking world rarely get to have.

In a future installment, I hope to report on what actually happens—whether I become merely an advisor, or whether I end up with clamps, hide glue, and a band saw in Kay’s living room.