We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Polishes. Most aerosol furniture polishes and some non-aerosols contain silicone along with petroleum distillates. These polishes are popular because they add shine, depth and scratch resistance for weeks at a time.

The truth behind craters and ridges.

If your finishing career has been limited to finishing projects you have made, you may never have experienced fish eye. But if you have done much refinishing, especially of furniture, you have surely seen fish eye.

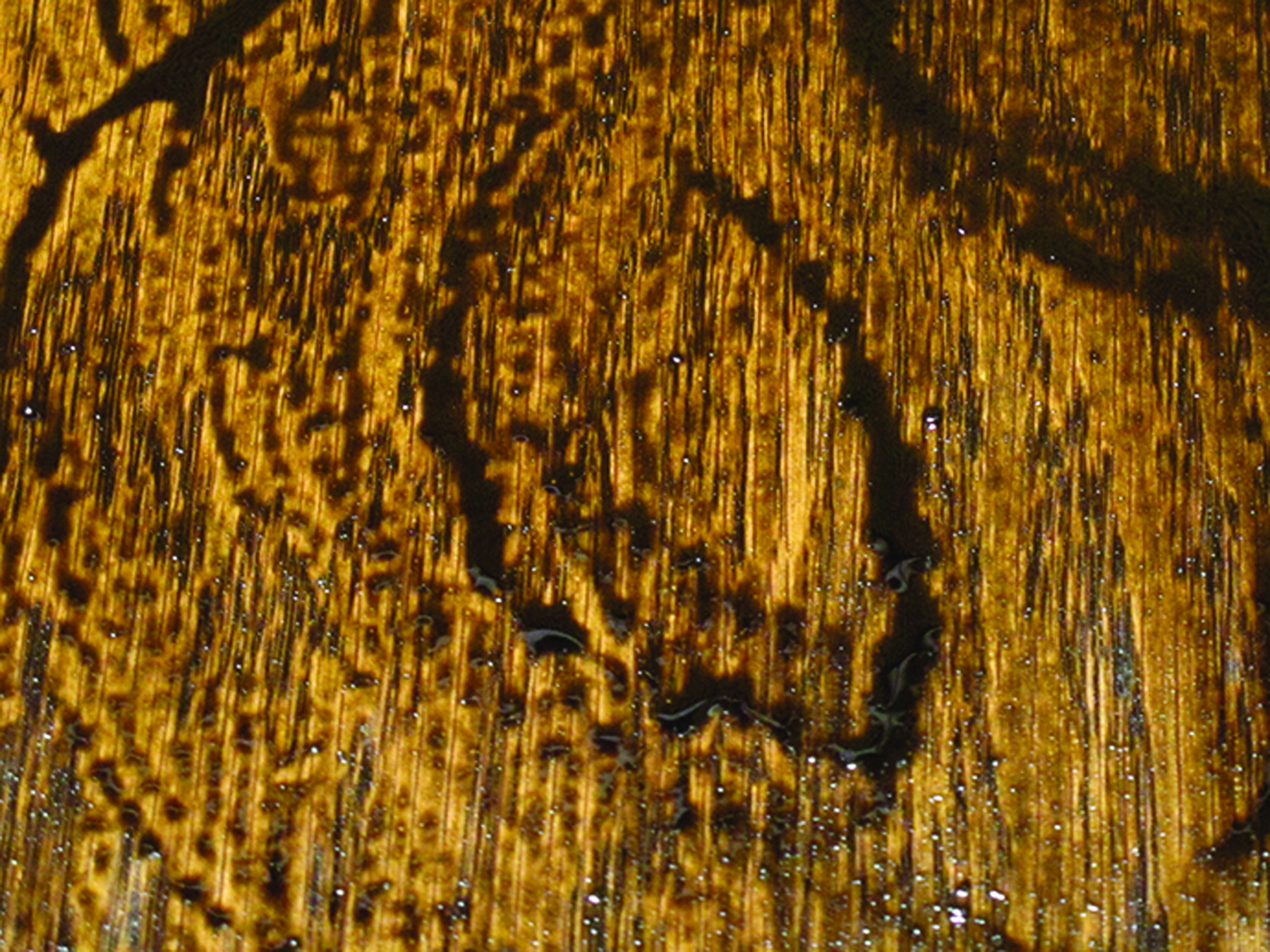

Fish eye is the finish crawling up to form moon-like craters or ridges within seconds of your having brushed or sprayed a coat of finish. You can actually see the finish move. The cause is almost always silicone contamination, so the first thing to understand is silicone and how it gets on furniture.

Silicone

Silicone is a synthetic material made from silicon (sand), oxygen, carbon, hydrogen and additional elements to make a liquid, gel, resin or hard plastic. You are surely familiar with silicone caulk, and you may have heard of silicone breast implants.

It’s the liquid silicone that we’re concerned with here because many furniture polishes, especially those packaged in aerosols, contain silicone. It’s a very slick oil, noticeably slicker than mineral oil if you compare by putting a drop between your thumb and finger and rub them together. It’s also totally inert, so it doesn’t damage anything.

If the silicone gets through a finish and into the wood – through a crack or rub through, for example – it will get in the pores and create a very slick area with such a low surface tension that most new finishes will pull away. This is what causes fish eyes.

Fish eyes can also occur on new wood projects. For example, you could be using a hand lotion that contains silicone, or you could have sprayed a silicone furniture polish or lubricant near the wood you’re finishing.

Silicone & Refinishing

When I began refinishing furniture in the mid-1970s, I encountered fish eye, of course. I was told by other refinishers, product suppliers, antique dealers, etc., that the culprit was Pledge and that I should discourage people from using Pledge. I dutifully obeyed.

I was also told that Pledge caused finishes to soften and become sticky, harden and crack (the opposite!), and that Pledge scratched finishes (the silicon), among other problems. But I would go into people’s homes and see dining tables that had been treated with Pledge for many decades and still looked great. I began to question what I was being told.

Slowly, I figured out what was going on. Finishes can soften and get sticky from contact with acids (body oils) or alkalis (cleaning products). They can get hard, brittle and crack simply from age, which can be accelerated by sunlight through a window. And they can get scratched from contact with all sorts of objects.

In other words, there are accurate explanations, but a refinisher without this information knew only what he or she had heard through the rumor mill. So the obvious question to the homeowner was, “Have you ever used Pledge?” The answer was almost always “Yes” because Pledge had a 60 percent market share. This just confirmed that Pledge must be the culprit.

Why are silicone furniture polishes so popular despite many people having heard they shouldn’t use them? Because the silicone doesn’t evaporate quickly like the petroleum-distillate solvents in other furniture polishes. The oiliness provides shine for a week or two.

It also provides resistance to scratches as long as it lasts, so the furniture maintains its near-new appearance much longer. And silicone has a low index of refraction, so the wood in a tabletop looks deeper and richer when viewed at a low angle.

Consumers love these polishes despite their bad reputation. It has created a quandary for manufacturers who can’t brag about the included silicone on their containers. Instead, they brag when they don’t contain silicone, “contains no silicone,” as if that is a positive.

Refinishers and others still discourage the use of silicone polishes (grouped together as “Pledge”), but the battle is lost. Maybe as much as 90 percent of all furniture polishes contain silicone. We just have to learn to deal with it.

Solutions

Stain. A stain will reveal silicone contamination by bunching up when you wipe or brush a wet coat.

The first step is to spot the potential for fish eye before it happens.

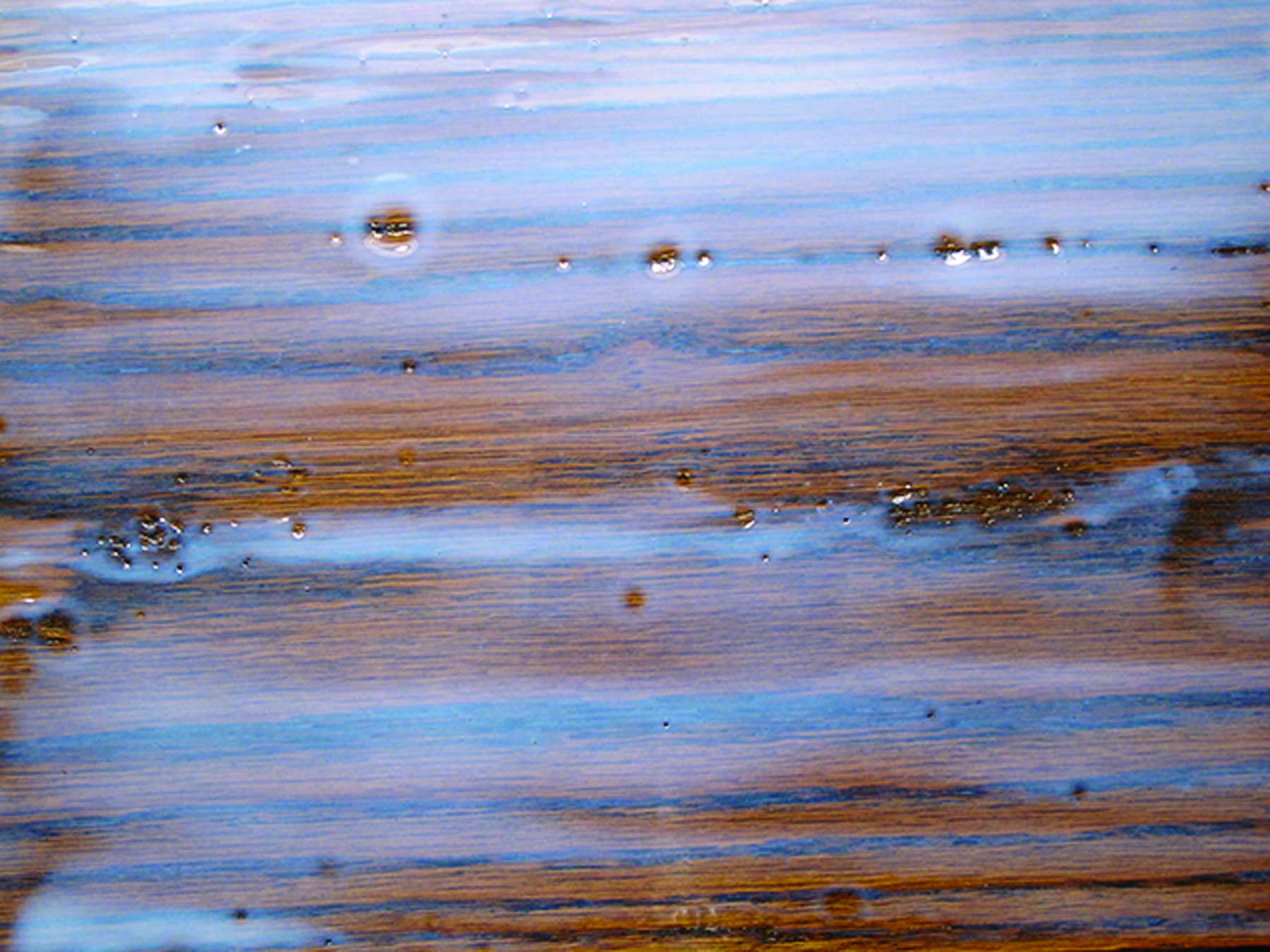

Liquid test. If you’re not staining, you can test for silicone contamination by applying a wet coat of solvent or water.

If you’re using a stain, you should see the fish eye develop right after a wet application. It disappears, of course, when you wipe off the excess because a thickness has to remain for the finish to crawl. If you aren’t using a stain, you could apply a wet coat of mineral spirits (paint thinner) or water to see if fish eye appears.

Shellac sealer. A sealer coat of shellac (right) will provide a barrier so another finish will go on top without fish eyes unless the contamination is very bad.

If the test is positive for silicone, there are three primary ways to deal with it:

1. Remove the silicone from the wood

2. Apply a sealer coat of shellac

3. Add fish-eye eliminator to the finish.

Silicone is oil, so it can be removed by washing many times with a solvent such as naphtha, mineral spirits, acetone or lacquer thinner. It can also be emulsified with an alkali such as household ammonia or trisodium phosphate (TSP) and water, then washed off with water. (The downside, of course, is that the water will raise the grain.)

Shellac is not affected by silicone unless the contamination is really bad, so shellac can be used as a sealer under another finish. If the shellac doesn’t provide enough of a barrier, combine it with one or two of the other methods.

Add some silicone. Fish-eye eliminators are silicone that lowers the surface tension of the finish so it flows out level. These products are available in paint stores and online catalogues.

If you are finishing with lacquer or varnish (oil-based polyurethane), add an eyedropper or two of fish-eye eliminator to a quart and stir well. With varnish, thin the eliminator first with mineral spirits so it mixes easier. Fish-eye eliminator is, itself, silicone, so it lowers the surface tension of the finish enough to level well. Once you have added the eliminator to one coat, you must add it to all coats.

A fourth, more difficult, method of dealing with fish eye is to spray many dustcoats of lacquer to get a build, then spray a coat that is wet enough to dissolve the dust but not so wet that it dissolves through and causes fish eye. This will take practice to get right, but it does work.

Not just a solvent-based problem. Fish eye can occur in water-based finishes, but emulsified fish-eye eliminators that mix well with these finishes aren’t widely available. So use a shellac sealer coat instead, or clean all the silicone off the surface before finishing.

If you don’t discover the fish-eye problem until you have already applied a coat or two of finish, it’s best to remove the finish and begin again, employing one or more of the above steps. You can also try to build some dustcoats and sand back until level, but this is difficult.

Worst case: Strip everything off and start over.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.