We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Spade bits get little respect among woodworkers. They are regarded as coarse tools that tear up the work surface – good for plumbers and rough carpentry at best.

Once you understand how to use them, however, you might change your mind about them because they are inexpensive and can do tricks that few other bits can do.

Before you rush out and buy a set from the home center, do yourself a favor and avoid the fancy ones that have a lead screw and magic coating. These cost a lot more, the coating is fairly worthless in woodworking and the lead screw puts the bit in charge of the feed rate.

Buy the simple, inexpensive ones that have a hexagonal shank (these won’t slip in the chuck). A set of 10 bits should cost about $10 to $12.

So here’s the No. 1 tip about using these bits: It’s all about how you start the cut.

Most woodworkers start with the bit at a slow rotation. This (and dull spurs) will chew up the surface of the wood right quick. Instead, place the bit’s lead tip lightly on the work and get the drill going at full speed before advancing the bit into the work. If you are using a cordless drill with a speed selector, choose high. If you have a variable-speed trigger, press it all the way.

Advance the bit slowly until the spurs engage the wood and define the circumference of the hole. Then you can dive in a little faster.

If you have never used a spade, this is where you will find out why they are so awesome. They cut quickly and refuse to clog.

The Infinitely Adjustable Bit

The other reason I use spade bits all the time is because you can adjust their diameter in infinite increments at the grinder. This trick allows you to create round mortises (in chairmaking, for example) that will fit your tenons bang on.

Let’s look at a typical problem – one I had today.

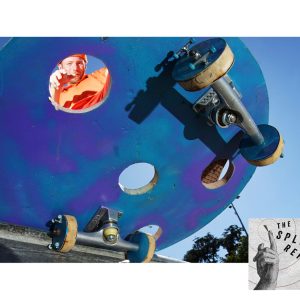

I had turned some rungs for an undercarriage and had gotten a wee bit aggressive on the lathe and turned the tenons down about .012” too small. Instead of throwing out the perfectly good spindles, I took a 1/2” spade bit to the grinder. (See the photo at the top of the entry. See that gap?)

I gently ground the long edges of the spade, taking care to grind both edges equally. (Note: You can also do this with a file.) Then I checked my work with calipers. When the bit was the same diameter as my tenon, I stopped grinding.

There are limits to what you can grind away, of course. Once the spurs are ground away, the bit will become difficult to use. That’s when I grind some bevels on the tip of the spade bit and transform it into a marking knife.

— Christopher Schwarz