We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

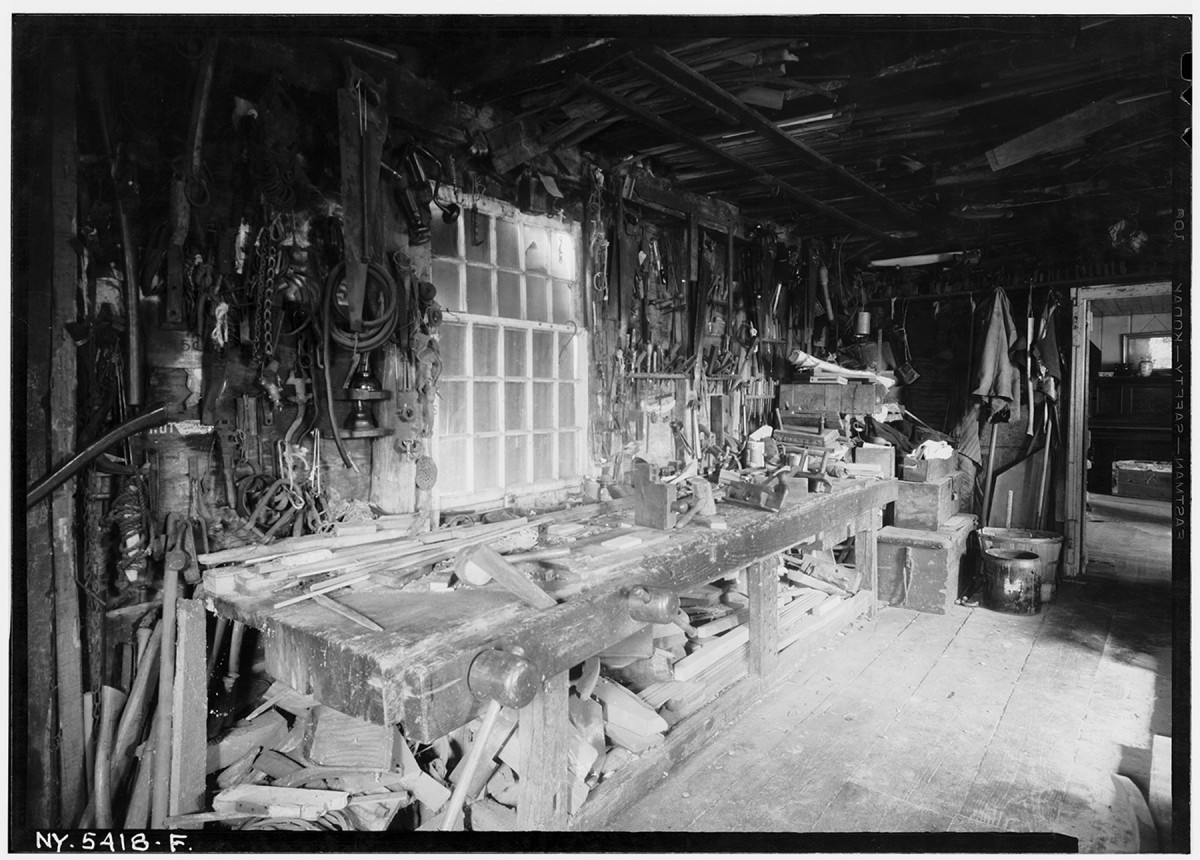

Luther Sampson shop. This 16′ x 32′ 18th-century joiners/carpenter’s shop in Duxbury, Mass., had been used by the school on whose property it sits as a storage shed. In 2012, restoration carpenter Michael Burrey, of Plymouth, Mass., got a look inside and was stunned, recognizing it as the oldest known shop in the United States on its original site.

Raking light through windows is the clear winner in a hand-tool shop.

In 2007, I was a speaker at Colonial Williamsburg’s Furniture Forum, and there I met Adam Cherubini. He was in costume in the parking lot, talking period furniture and tools to anyone who’d listen. If you know Adam, or have seen him in a presentation, then you know he breathes this stuff. Deeply.

As I started to find out about him, one thing I learned was that he wrote a column called “Arts & Mysteries” for this magazine. We crossed paths several times after that, and he got me connected to the magazine, suggesting I contact some guy named Chris something-or-other. During one of Adam’s sabbaticals, I even wrote a guest column. Then for a while Bob Rozaieski of the blog Logan Cabinet Shoppe filled in and wrote it. Now it’s my turn to take it for a while.

As I write this first column, I am in between workshops. For the past two months, my hands-on woodworking has mostly been splitting wood and spoon carving. But my mind is all over the place as I think about what I want in the next incarnation of my workshop.

As a hand-tool woodworker, I don’t need much in terms of space or equipment for a shop. I have a couple of benches and a pole lathe. Beyond that I need some room to store stock, patterns, tools, works-in-progress and not much else.

Readers of this magazine are quite familiar with some of the trends in woodworking today. “Roubo” benches, wooden-bodied planes, re-sawing by hand, carved decoration, inlay work, foot-powered lathes – all these things and more are being explored in tremendous detail by craftsmen and craftswomen both amateur and professional.

Period furniture continues to enthrall woodworkers and their customers even after all these years. They even have their own society: the Society of American Period Furniture Makers (members work with both hand and power tools).

But what one thing do we (I count myself among this “granfalloon”) mostly overlook? Lighting. Many of us are in workshops that we did not get to design in full. My first one, like those of many, was in a basement. After that, I graduated to the second floor of a chicken coop. Not much in the line of windows there. The shop I had for the last 20 years had lots of windows, but it was part of a museum exhibit.

So for several reasons overhead lighting was the default. Once a hurricane left us without electricity for most of a week, and I had great raking light each day until about 3 p.m. During winter, when the museum was closed, I used to go in on weekends and work without the lights.

Historic Evidence

Dominy shop. Now reconstructed at the Winterthur Museum, Garden and Library in Winterthur, Del., the Dominy woodworking shop was used by four generations of craftsment in East Hampton, N.Y., from the mid-18th through mid-19th centuries. This image, from the Historic American Buildings Survey collection at the Library of Congress, shows the shop before it was moved.

We know that period, or pre-industrial, shops had workbenches, lathes and other work areas positioned where they could make use of daylight from the windows. This results in raking light – light that shines across the work to leaves shadows that help the eye to see definition, shaping and depth.

Luther Sampson’s 18th-century joiner/carpentry shop in Duxbury, Mass., has benches lining both long walls of the main room, with a third bench converted to a lathe on the end wall between them. There are now windows over each of the long benches. We assume there were windows in similar positions originally; their size and placement is unknown.

I first visited this shop after the hurricane/daylight experience in my shop. While others were discussing how many workmen might have been in this shop at once, I was wondering if it was just one or two, and they moved from one bench to another as the light changed during the day.

Light matters. Overhead light washes everything out and makes it look flat. With raking light, shadows and lines are highlighted, which makes it much easier to see the work.

The Dominy shop (originally in East Hampton, Long Island) is now installed at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The original shop was measured and partially photographed before being disassembled in 1946. Charles Hummel’s book, “With Hammer in Hand” (University of Virginia), includes a couple of photos and a floor plan that were part of the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1940. There were two long benches in the Dominy shop; one nearly 17′ with two windows over it. The smaller one, at a little more than 12′, had one window.

The Dominy shop (originally in East Hampton, Long Island) is now installed at the Winterthur Museum in Wilmington, Del. The original shop was measured and partially photographed before being disassembled in 1946. Charles Hummel’s book, “With Hammer in Hand” (University of Virginia), includes a couple of photos and a floor plan that were part of the Historic American Buildings Survey in 1940. There were two long benches in the Dominy shop; one nearly 17′ with two windows over it. The smaller one, at a little more than 12′, had one window.

I’m disinclined to research the history of overhead lighting; but I know I don’t like it. It might be good for an operating room, but for a workshop my preference is for windows near the bench. Overhead lighting is flat, with no shadows. I’m a carver among other things, and overhead lighting makes it hard to see the depth of your work. To really assess what’s happening, you have to pick the workpiece off the bench and hold it so the light crosses it. And that slows you down.

Aside from the few extant workshops, historical paintings, photographs and other artwork help us to understand the relationship between the bench and the windows. Often the bench is 90° to the window; in other cases it runs parallel to and just under the windows, like in the Dominy and Sampson shops.

While I search for new shop space, I’ve been reviewing some of my earlier research. For me now, it’s vicarious-woodworking as I peer over the shoulders of period workmen. I hope you’ll read along with me; maybe we’ll learn something.

Peter is a teacher of 17th-century woodworking and host of several videos from Lie-Nielsen Toolworks. Read more from him at pfollansbee.wordpress.com.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.