We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

When I was taught to sharpen in 1992, the flat back of the iron was holy ground. We were taught to flatten it completely and polish it like a mirror. Never mind that none of the old tools we were buying at flea markets looked like that.

With the old tools, there was rarely much work on the back, and forget a mirror polish. If there was any significant work on the back, it was up at the tip only.

Thanks to David Charlesworth and his “ruler trick,” many of us have left the dogma of a flat and polished reference surface behind. What matters is a sharp edge and the cutting geometry of that particular tool. Some should have a flat back. Most don’t need it.

Earlier this year, woodworker Carl Bilderback sent me a great little book called “Carpenters’ Tools” (1950, Frederick J. Drake & Co.) by H.H. Siegele (pronounced like “seagull” more or less). Siegele was a crusty carpenter from the old school who lived in Emporia, Kan. His book is a treatise on all the tools in the carpenter’s kit, including how to maintain them.

There is a lot of great information in the book that doesn’t get much coverage, such as how to use a scrub plane. This weekend I spent some time with his section on sharpening, just for kicks. Here’s what he says about sharpening a block plane.

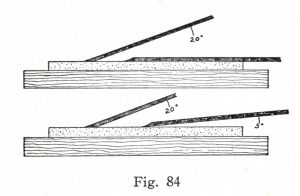

“Fig. 84 shows two ways to finish the sharpening of a block plane bit on the oilstone. At the top is shown the bit in a 20-degree angle for finishing the bevel, while the back is finished flat against the stone. At the bottom the bevel is also finished on a 20-degree angle, but the back is finished at about a 5-degree angle. Both of these methods are good, but the bottom method is mostly used. It is a little better than the method shown at top, especially when the bit is hollow-ground, as most bits are when a small grinder is used.

“Fig. 85 gives two enlarged details of block plane bits in part, showing the two methods of sharpening such bits. The upper one shows a 20-degree angle for the bevel sharpening, and a 5-degree angle for the back, while the bottom shows a 23-degree bevel sharpening and a flat sharpening for the back.”

Note that Siegele doesn’t recommend this procedure for bench planes, only for block planes. Why? He doesn’t say, but I suspect that lifting the iron as you finish the back helps remove some of the wear that the back receives in a block plane. Some people call it a “wear bevel.” Please don’t make me talk about the “wear bevel.” Let’s just say that the bevel that faces the wood gets more wear than the part of the blade that faces the user.

In any case, Siegele wasn’t using a ruler to produce the back bevel, but the idea is the same: Polish the tip.

— Christopher Schwarz

Want to know more about sharpening? I heartily recommend Ron Hock’s “The Perfect Edge” (Popular Woodworking Books). Hock, the owner of Hock Tools, tells you everything you need to know in an easily digested format. It’s good stuff and should be on everyone’s bookshelf.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

“Please don’t make me talk about the “wear bevel.””

BEWARE THE WEAR BEVEL! An evil monstrosity that sneaks up on you and takes away the fine edge you have honed to perfection.

RileyG

Woodcarver who has worn groves in knives from working the wood.

I good post, but I’ve been reading you long enough now to know that the only reason you wrote it is so you could use the phrase “polish the tip”.

Were bevel?

Izzat some new

Laurell K. Hamilton

creation?

Night of the Were Bevel?

Hi there !

I truly agree with mr Porcaro, but i wish to add some thought on back bevels.

One as many knows back bevels could be used to increase the effective pitch on BD planes to emply them as scraper planes

On the other way and my favorite one is to use back bevels on bevel up miter planes to get a low pitch and clearer cut on end grain surfaces, but be wared, if you have got a 20º bevel and add 5-10º back bevel everybody can guess this is too risky to long life cutting edge and it is stupid to use it with figured and exotics species, so the focus is to create a keen edge balancing the upper and back bevel of the blade and not to forget the wood in our hands.

The key to sharpening success is the pressure my dear buddies

Chris,

It seems to me that the sharpening angles you are mentioning here would lead to a very fragile edge. Certainly the 20 degree included angle from the top of figure 84, but also with 23 and even 25 degrees I would expect micro-chipping or folding over of the edge (ie. rapid dulling). Can you comment on the durability of these edges?

Hi Chris,

Yea, I think a back bevel is helpful with bevel-up planes, particularly because it is a faster way to remove the wear bevel on the bottom (“back”) of the blade. That wear bevel is, in my opinion, the chief disadvantage of BU planes.

But, a couple of additional points:

1- The back bevel has to be small enough to be contained in the part of the blade that is extended into the throat. This should be easy though. Otherwise, the support of the blade on its bed, one of the big advantages of BU planes, is compromised.

2- For a 12 degree bed BU plane (which is most of them), a 5 degree back bevel yields a clearance angle of only 7 degrees, which is not much. This may interefere with the plane’s function, and at least will tend to aggravate wear on the back of the blade.

That is one of several reasons why I think most BU planes ought to be bedded at 18-20 degrees, not the usual 12 degrees. Interestingly, Karl Holtey has sells a BU plane at 18 degrees, and the L-N #9 is 20 degrees, and, of course, there are plenty of block planes at 20 degrees.

I really think the reason 12 degrees is usual for block planes is that the 20 degree models aren’t as easy to grip, but that is not an issue with BU smoothers, jacks, etc.

But that’s another can of worms.

Thanks for your post.

Rob

Nice to know. It’s really not hard to freehand a back-bevel. I do that for the irons in my smoothing plane and jack plane, and the technique works fine.

Block here as in bevel up and bench as in bevel down, I presume?