We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

In early Gustav Stickley pieces, doors with divided lights were joined with mitered mullions. It’s an intriguing look, but was used only for a few years. My next project for the magazine has a divided door, and even though I haven’t been able to find an original example of the piece I’m building with mitered joints, I decided to build mine with that detail. I like the way it looks, so I took the challenge of figuring out how it goes together, and how to make the parts.

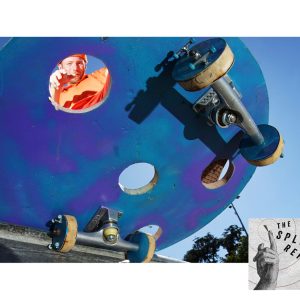

There is a lot going on in a small space. The interior parts are only 1-1/4″ wide and there is a rabbet on the back for the glass and glass stops. The openings are small, but the joints need to be strong to support the weight of the assembled door and the glass. Merely mitering the pieces and depending on glue didn’t seem practical; the parts would slide around during assembly, and the photos I’ve seen of original pieces indicate that the central mullion is continuous from top to bottom. I decided on mortises and tenons on the outer joints, and half-lap joints in the middle.

It goes together quite nicely in SketchUp, but I decided to get some practice in before building the cabinet. I enjoy the rhythm of building, and I can’t get that going if there is a part of the process on the horizon that I haven’t figured out. In this case I was concerned about the joints in the middle of the door, where four mitered corners all come together. I figured out a really clever router jig that would cut the openings except for the rounded corner in the center, which I would need to remove with a chisel. I’m better at chiseling than sawing so it seemed like a good approach.

One of the reasons that I’m good at chiseling is that I’m not so good at sawing. I don’t get enough practice to be able to walk into the shop, pick up a saw and cut a perfect joint. I need to warm up with some practice cuts first. Because of this, my inclination is to think of the saw last. I should have thought of it first because my router jig didn’t quite work. I could have made it work, but that would have involved several hours of fiddling with it to overcome the small variations between the bit and bearing and the size of the parts. The jig wasn’t a total failure; it came close but left either a small flat between the points, or a small opening. I was aiming for something finer.

So I spent a couple hours working out with the saw instead of refining the jig. I added to the fence to keep it a little farther away from the corner, and it works nicely to remove the waste and leave a flat surface, after the saw cuts are made. To really make this joint look good, I need an X exactly on the center of the board. The kerf of the saw needs to fall on opposite sides of the line on each side to leave a nice point in the middle.

I almost have it. I took a few extra steps to locate my cuts and get the saw started, and with a few more practice joints I’ll have it. As for the router jig, maybe I’ll submit it under an assumed name as a trick to some other magazine.