We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

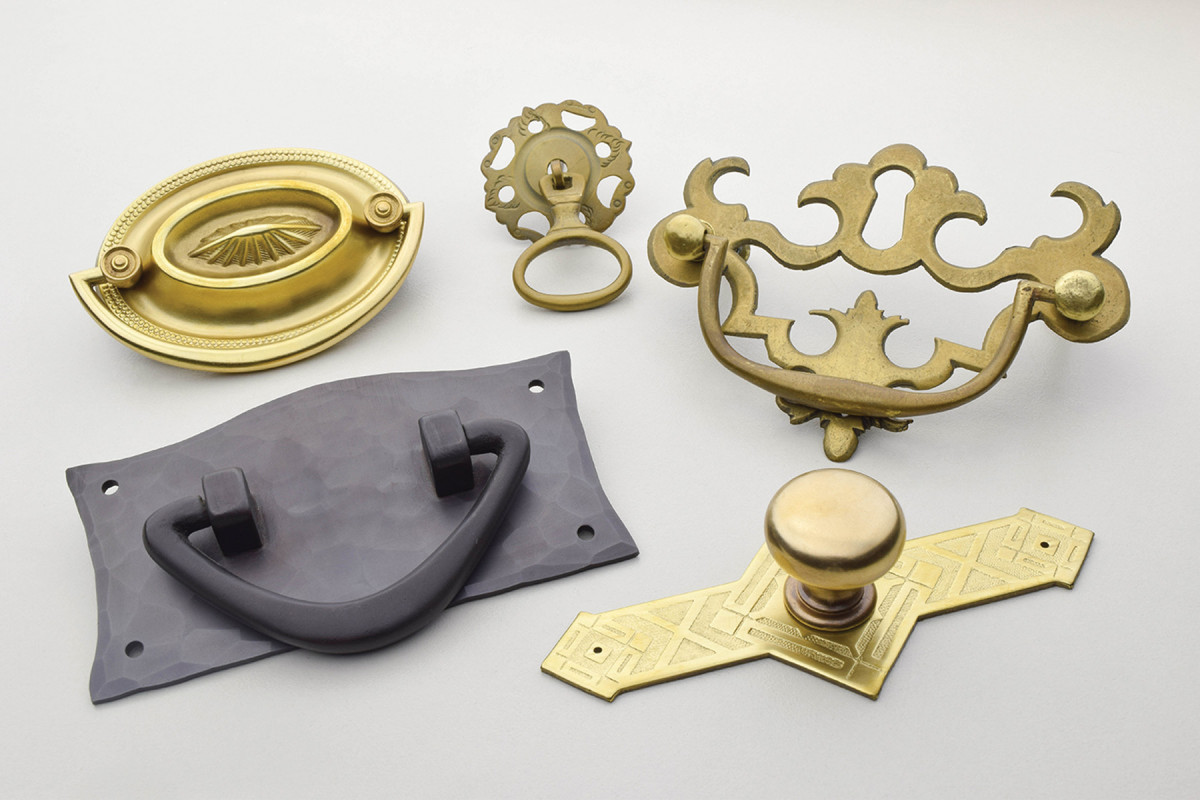

250 years of hardware history. Pieces from Ball & Ball, Craftsman Hardware Company, Horton Brasses and Londonderry Brasses.

A concise chronicle of furniture hardware styles to help you build it better.

One question I am often asked is, “What hardware should I use?” And the answer is usually, “It depends.”

What did you build? Are you refinishing or restoring? Is your work an original or a reproduction?

Whether you’re looking to stick to tradition or break from it, I believe it’s helpful to understand the history behind the hardware – where it’s been and where it started – when selecting knobs and pulls for your pieces.

To provide a little more insight, I’d like to walk through the main historical periods of American furniture brasses. To keep things brief, I won’t get into hardware from other parts of the world (French and German hardware can be quite nice, though). I guess I could explore Shaker hardware, but I just don’t find wood knobs that exciting.

William & Mary

William & Mary drop pulls. Delicate chased rosettes with drops mounted on cotter pins. Dutch drop by Ball & Ball, teardrop by Londonderry Brass

In 1660, England’s King Charles II had just come out of exile to reclaim his throne. (I should note that American furniture brasses, with the exception of the Craftsman style, originated in England.)

This period is known as “The Restoration,” and we know furniture and hardware from this era as William & Mary style (they took the reign(s) in 1689). The style, at least in terms of hardware, was produced from about 1660 to the early 1700s, and was largely made of brass, with some occasional cast silver pieces.

William & Mary hardware and furniture were generally quite ornate, with features such as Dutch drops or teardrops paired with rosettes in a variety of patterns, from cast florals to hand-chased diamonds to the more subdued round rosettes. Drops were most commonly fastened with cotter pins, although some pieces were fixed with posts and fingers to create cupboard turns.

Queen Anne

Queen Anne pulls. A pierced pull from Ball & Ball.

In the years to follow, the hardware world saw manufacturing techniques advance, resulting in shapes of greater detail – a style known as Queen Anne. The Queen Anne era ran from the late 1600s to about 1750. This was also the first time the now-iconic cabriole leg was used on furniture pieces.

Hardware of the era was delicately cast with decorative designs such as piercings or chasings on the face. The chasing patterns were small, decorative stampings, almost always floral, and applied with a hammer. Drawer pulls were typically fastened with either a post and nut or cotter pin. A short and stubby threaded screw was cast into a knob’s back – we refer to this as a breadboard screw, though technically it’s a hanger bolt.

Chippendale

As we move into the Chippendale period, some of you might argue for a variety of specific dates. That’s understandable (there’s certainly some discrepancy), but here I define the era as 1754 to about 1790 and note that the time periods overlap.

Thomas Chippendale was a man of many talents, most notably design, furniture making and writing. His book “The Gentleman and Cabinet Maker’s Directory” defined the era of furniture and its metalwork, providing the definition we still use today.

Various pulls. Chippendale in a high polish, an oval-shaped Hepplewhite and a typical floral Victorian, all from Horton Brasses.

Chippendale brasses are highly decorative brass plates, often called bat wing brasses, with delicate bails and posts. It is important to realize that in this time period, the metal itself was extremely expensive – a far greater production cost than labor. Larger pulls were typically formal and most commonly found on expensive pieces of furniture. Brasses were always hand-polished, as they better reflected light that way. In the days before electricity, evening lighting was at a premium, so brasses of all types served both form and function.

George Hepplewhite and Thomas Sheraton followed in Chippendale’s footsteps. Hepplewhite’s book “The Cabinet Maker and Upholster’s Guide” (published posthumously in 1788) popularized a new, lighter design style with delicate inlay and curvilinear forms.

A few years later, Sheraton published a four-volume book called “The Cabinet Maker’s and Upholster’s Drawing Book.” The publications were widely influential, and we have come to know the furniture and associated hardware as Hepplewhite, or Federal, style.

The tail end of the 1700s and start of the 1800s saw development of new metal-working technology. Tool and die makers of the time were enamored with the fine detail they could now put into metal, resulting in the arrival of stamping as a metal-working technique. Toolmakers started producing beautiful stamped plates and knobs to suit the furniture inspired by Sheraton and Hepplewhite.

American tool and die makers tended toward themes celebrating patriotism (eagles and flags were popular), or imagery such as flowers and wheat that represented the New World’s bounty.

It’s my opinion that this style of hardware was the finest ever produced.

Victorian

Authentic Craftsman style. Heavy metal with hammered surfaces made from solid copper and with a patinated finish. (Craftsman Hardware Company, Marceline, Mo.)

Throughout the 1800s, both Chippendale and Federal styles experienced revivals, and as the West was settled, much of the furniture and hardware produced was utilitarian in nature. The next new period, however, was the Victorian era.

The motto for the Victorian period could have been “anything worth doing is worth doing to excess.” Victorian hardware was highly decorative, with elaborate, flashy patterns stamped into very thin metalwork. This was the first era of mass-produced hardware, as thousands of these pieces were stamped, fitted to production-line furniture and shipped everywhere. A downside of mass production, of course, is the too-common drop in quality – a lot of junk got made at this time – but some pieces were quite spectacular. The Eastlake style in particular held up very well.

Craftsman, Arts & Crafts & Mission

What we now know as Craftsman, Arts & Crafts and Mission styles all began as rejections of Victorian excess.

Out went the pretty floral patterns and mass-produced pieces. Designers such as Gustav Stickley, Charles and Henry Greene and William Morris created new, original designs that shared little (save joinery) with the past.

Patterns were typically made from heavy brass, copper and bronze, then hammered and patinated to a very dark finish. At the time, the idea was to let the work show but, ironically, this may be the first time period where the brasses were patinated to artificially create a new look.

So how does this all relate to you, the furniture maker? Knowing what came before can help guide your choices. This applies to joinery, finish and, of course, hardware. You can adhere to or break from tradition – either path can lead to success, but your work will always be better if you first learn your history.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.