We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Restoring one of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s greatest accomplishments 150 years after it originally opened.

LOCATED AT: 215 Sauchiehall Street Glasgow G2 3EX, United Kingdom www.mackintoshatthewillow.com

Willow Tea Rooms Trust www.willowteamroomstrust.org

As an architect and designer, Charles Rennie Mackintosh is synonymous with Glasgow—the city where he spent most of his life, and where several of his most significant commissions can be found. It is therefore unsurprising that his mercurial approach to design, which encompassed symbolism, Arts and Crafts, and Art Nouveau, ultimately became known simply as “the Glasgow style.”

In July 2018 a devastating fire destroyed much of the Glasgow School of Art, one of the most recognised and celebrated buildings designed by Mackintosh. However, only a three-minute walk around the corner, another significant Mackintosh landmark was undergoing a dramatic rebirth. After four years of painstaking restoration to both the structure and fitout of the building, costing nearly £10m, Mackintosh at the Willow re-opened its doors 150 years after it originally launched.

Introducing Tea Rooms

The Willow Tea Rooms at 217 Sauchiehall Street were first opened on October 29, 1903 by the entrepreneur Catherine Cranston, who took advantage of the rise in popularity of the temperance movement to present tea rooms as a morally appropriate recreation and meeting place. Despite being the fourth such tea rooms at which Mackintosh had been engaged by Miss Cranston, the Willow Tea Rooms were the first where Mackintosh was given total control over the design, both internal and external. The result was a tour de force in design, allowing the notoriously perfectionist and detail-orientated Mackintosh to design every element of the Tea Rooms, from remodelling the exterior of the building (an 1860’s tenement block), to the interior decoration, to each item of furniture and even the cutlery.

As an exercise in design, the Willow Tea Rooms are breathtaking in terms of both scale and the astonishing level of consistency in design language. Recurring motifs echo across plaster friezes, stained glass, and furniture throughout the four floors. Sadly, through changes of use and ownership much of the original furniture was lost, and the Willow fell into a serious state of disrepair until an ambitious plan to rescue the important Mackintosh landmark was hatched in 2014. Prompted by a forced sale which would have likely resulted in the closure of the tea rooms and the remaining Mackintosh pieces being acquired by private collectors, the Willow Tea Rooms Trust was established as a charity in 2014 and purchased the building with the intention of faithfully restoring the tea rooms to the condition they would have been in when first opened in 1903. That project came to fruition when Mackintosh at the Willow (as the tea rooms are now known) opened its doors on 2 July 2018.

The Front Saloon and Back Saloon are furnished with Mackintosh’s black stained box arm chairs and ladder back chairs. The Gallery mezzanine features the same furniture as the Front and Back Saloons.

The sumptuous Salon de Lux is furnished with silver furniture, requiring an involved finishing process.

The booths of the Billard Rooms echo the black stained furniture of the Front and Back Saloon.

Restoration—Introducing the Makers

The restoration project was undertaken with an almost obsessive focus on returning the tea rooms to precisely the condition they were in in 1903. The result is a 200-seat restaurant, containing 400 items of reproduced furniture, and which faithfully follows the designs and layout originally envisaged by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. The ground floor comprises a Front and Back Saloon typified by ladder backed chairs and box armchairs in black stained oak. The first floor Gallery is a mezzanine looking down onto the ground floor, and shares the same furniture with that lower floor. The second floor houses the iconic Salon de Lux with its eye-catching silver highbacked chairs and matching tables. Finally, the Billiard Room on the third floor echoes the ground and first floors with black stained booths.

Reproducing 400 pieces of furniture is a significant undertaking, and the Trust undertook a rigorous process to identify craftsmen who could produce high quality Mackintosh pieces, while working from a paucity of original designs and extant examples. That process included inviting a shortlist of six furniture makers to construct a sample chair for evaluation. Three Scottish furniture makers were ultimately engaged to reproduce all of the furniture:

- Glasgow based Bruce Hamilton has an international reputation for producing Mackintosh furniture, and constructed the 33 arm chairs used in the Front Salon, Back Salon, and Gallery;

- Furniture maker and artist Angus Ross has an international reputation for design and is frequently included in exhibitions in the UK and United States, and was commissioned to produce the 125 ladderback chairs used in the Front Salon, Back Salon, and Gallery; and

- A team from Character Joinery—experts in joinery and furniture for conservation and listed building projects—comprising of three cabinetmakers, two apprentices and a French polisher, headed by director Kelvin Murray, reproduced the furniture for the Salon de Lux together with the waitress stools and the iconic curved cashiers’ order chair in the Back Saloon.

Design and Research

The lack of surviving scale drawings, and only a few surviving original pieces of furniture, represented a significant challenge, all the more so because the Trust insisted on exact reproductions in material, scale and finish. That challenge became an opportunity, as Kelvin Murray explains: “with hindsight it was the best thing that could have happened, as it really got me to understand Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his cabinetmakers.” The reproduction process therefore started with detailed research, following a trail of the few surviving original pieces, sketches by Mackintosh, previous research by other makers, and piecing together fragments of materials or processes.

Table ready for tea in the Gallery.

One constant thread that runs through the investigatory phase of the restoration is how willing Mackintosh collections or scholars were to provide the furniture makers with access to examples of the furniture, or research materials. All of the makers were given access to original pieces held by the Glasgow School of Art from which to take measurements and drawings. Bruce Hamilton observes that: “during the inspection of the original chair at the Glasgow School of Art I had to take into account slight discrepancies in some measurements which I put down to shrinkage or the possibility of inaccurate manufacture of the original piece.” This variance in dimensions was also noted by Angus Ross when comparing two different ladderback chairs.

Front and rear views of the box arm chair designed by Mackintosh.

Following the fire at the Glasgow School of Art in 2014, no known surviving examples of the Salon de Lux tables or coat stands exist, and so those pieces were developed entirely from photos of the tea rooms taken from 1905 and 1980, as well as sketches by Mackintosh. Fortunately, Spanish luthier Josep Melo had studied Makintosh in the 1970s and 80s, including taking drawings of the Salon de Lux round table and hat stand. Josep provided Character Joinery with his drawings, which then allowed the team to not only reproduce the round table, but to transfer the proportions and construction details to the square and rectangular tables.

What first seems to be a simple piece is brought to life with curves and chamfers.

Timber selection was also approached through analysis of surviving furniture, as well as fragments of furniture destroyed in the Glasgow School of Art fire. All of the chairs were constructed from oak, while the coat stand was mahogany, and the Salon de Lux tables from birch and tulipwood.

Life is the leaves which shape and nourish a plant, but art is the flower which embodies its meaning.—Charles Rennie Mackintosh

Far from the Finish Line?

Determining the appropriate finishes for the furniture was a critical stage of the research, not least because the black-stained furniture had to be consistent while being produced by three different makers. A microscopic examination of a fragment of an original black stained Mackintosh stool led to the use of a black stain, black oil, and topped with black wax, which the Trust mandated all three furniture makers to use.

The silver finish for the Salon de Lux furniture required a different approach. While the surviving chairs had been repainted in the intervening years, some time before the Glasgow School of Art fire a sample of the original silver finish had been discovered on a coat stand, where it had been protected from subsequent paint applications by the coat hook. The original finish was sent for analysis, and Kelvin recalls that “to my horror, the results came back with the finish layers. A white undercoat primer, then gold flake, finally finished in aluminium flake. This sent me back to the research books and two months of research and study.” The silver topcoat was reproduced by brushing on a mixture of 12 micron sized aluminium flake with resin, in a similar technique to that used for gilding, following which the aluminium would be buffed and polished to a high sheen. While not a straightforward or simple process, it is one which Kelvin considers to have been worthwhile as “this resulted in a real metallic look but also in the correct light you can see the gold leaf underneath which gives the finish on the chairs a real depth.”

Building the Furniture— An Opportunity to Improve

While many of Mackintosh’s designs call for bold forms, a close examination reveals many subtle design elements, such as the changing depth of chamfers, subtle tapers, and slight curves. These elements, according to Kelvin Murray, “completely lift the designs and adds so much to the meaning of the pieces.” In practical terms, Kelvin’s team approached the restoration on a hand tool only basis, as “to actually work with modern machines in a batch production was impossible and many components could only be shaped with hand tools. This determined our approach. We machined the timber to square stock sections, and then everything was made by hand.”

The front and back view of the ladder chair. The back makes wonderful use of negative space.

If there is a weakness to Mackintosh’s furniture designs, it is that they do not always take into account the structural attributes of the natural material. Put simply, Mackintosh was an architect and designer, not a furniture maker, and as Kelvin Murray explains “one of the reasons that the chairs from the salon don’t survive was that they were designed aesthetically first and foremost and construction came second.” Indeed, reliance on undersized tenons, or ignoring the strengths and weaknesses of woodgrain, has meant that many original pieces have failed in the intervening years. While the Trust was clear that the furniture needed to be visually faithful to Mackintosh’s designs, the makers recognised that to reproduce furniture which would withstand the daily rigours of use in a busy tea room would require some hidden improvements.

Reproducing the 125 ladder back chairs involved cutting 3250 mortises and tenon joints, all of them cut by hand.

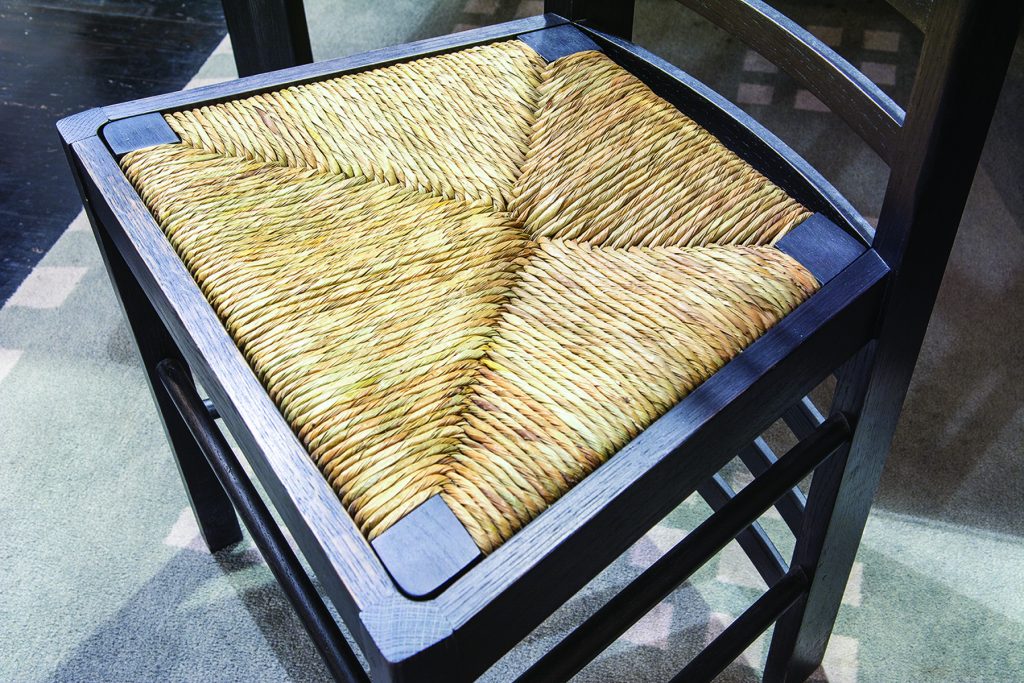

The rush seats were woven using traditional techniques, which each set taking a day to weave.

Kelvin recalls of reproducing the tall salon chairs “The backs of the tall salon chairs were tapered and curved as were the backs of the small chairs” and the originals “were made from one solid oak plank then carved and shaped by hand”, an approach which has the potential to increase grain runout and weaken the structure. In contrast, for the reproductions Character Joinery “constructed the backs from oak veneers laminated to the overall thickness, then using a spoke shave worked them to the shape. This gave a stronger back panel which would work better in a modern central heated environment.” Similarly, “the mortise and tenons on the legs and seat frames were so fine that they would be the first to break down, and so we changed the internal joints to dominos where necessary, as this gave us more glue surface and a stronger joint.”

The high back chairs in the Salon de Lux were built with laminated oak to mitigate the structural weakness of the originals.

Angus Ross also found that many of the original ladder back chairs had failed, and that many of the surviving examples have avoided failure due to the addition of reinforcement to the curved rails. The primary reason for the failure seems to have been that the curved rails were cut out of solid timber, rather than being steam bent, and it is possible that stock selection for the rails did not always minimise grain run out. As much of Angus’ work involves steam bending for chairs or sculptural elements, that method of construction was adopted in order to achieve stronger components. Once the 13 rails for each chair had been steam bent, the tenons were then cut by hand.

One of the most challenging reproductions was the curved cashier’s order chair in the Back Saloon which features a large crescent-shaped latticework back atop of a coopered base, and which Kelvin estimates took six weeks to complete. Kelvin explains that while this iconic piece has been reproduced many times, often “the components have been simplified for production, for instance the front vertical rails which in most reproductions are straight, but in the original they are tapered and shaped as is the front base cabinet.” This was therefore another piece where the design required a hand tool approach, particularly reproducing the latticework, which was a painstaking process as “every little lattice infill has to be shaped and fitted individually” in order to fit the curvature of the back. The latticework also offered an opportunity to improve on the original construction, in which the cross pieces were pinned in place. In contrast, Character Joinery dowelled each infill so as to create a stronger frame.

The curved cashier’s settle separating the Front and Back Saloon.

Hidden Details

The strict attention to detail continued in the Salon de Lux, particularly with the glazed petal details of the table legs which echo the floral themes of the stained glass and artwork found throughout the tea rooms. It fell to Kelvin to prepare the petals, “individually carving 188 timber petals for the tables, a task that took me just under 3 weeks.” The process for making the petals started with marking “all the petals out onto tulipwood timber and cutting out the centres with a fretsaw,” before cutting a 2mm x 2mm rebate for the glass insert “with a small hand held router then cut out the outside shape on the fret saw.” After this everything was shaped and carved by hand then finely hand sanded ready for gluing into the leg frames. What is remarkable about this devotion to accurate detail, at least to the outside observer, is that the petals are obscured when the tables are dressed with table cloths. Kelvin explains that, “For me is the reason that the Willow Tea Room is such an important piece of architectural heritage. It is the minute detail to attention that creates the whole grand experience.”

The iconic high back chair from Salon de Lux.

Chamfers of changing radii are a common feature in Mackintosh’s designs.

188 petals are required for the furniture in the Salon de Lux, most of which are hidden from view by table cloths, offering a wonderful surprise for those who look carefully.

The umbrella stand in the Salon de Lux.

A Landmark Rescued

Mackintosh at the Willow offers a unique opportunity for Mackintosh aficionados to see, and use, faithfully reproduced Mackintosh designs in the context for which they were intended. As an exercise in reproduction and craftsmanship, the restoration is breathtaking in terms of both the attention to detail and scale of work. As Kelvin Murray observes, “With every batch of reproduction ever done on Mackintosh, not one is produced exactly to the original, it is too time-consuming and would not be profitable to attempt. This is what made this commission so important; for the first time the pieces had to be done exactly as before.” The restoration is also a celebration of the very best of Scottish craftsmanship. As my family sat in the Front Saloon for afternoon tea, I could not help but wonder what Charles Rennie Mackintosh would make of the restored tea rooms. I rather think that he would have approved of the focus on accuracy and detail pursued by the Trust. PW

Stained glass in the door to the Salon de Lux echoes the motifs found in the furniture and decoration in the other areas of the Tea Rooms such as the fire place in the Back Salon.

Mackintosh created a consistent design language for the William Tea Rooms, which ties together the furniture, internal and external decoration as a unified whole.

See more from Kieran Binnie at overthewireless.com.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.