We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Here is a question that has been going through my mind for more than a decade: When an 18th-century French woodworker started building a workbench, what was the moisture content of the wood? Had it been seasoned for many years? Freshly cut? Something between?

Lots of modern people have speculated about the answer, but I have yet to find an historical source that answers the question to my satisfaction.

A.J. Roubo doesn’t mention the moisture content of the wood for a workbench in “l’Art du menuisier,” his 18th-century multiple-volume masterpiece on the craft. In reading over Roubo’s section on the bench, here are the parts that mention the wood and its qualities.

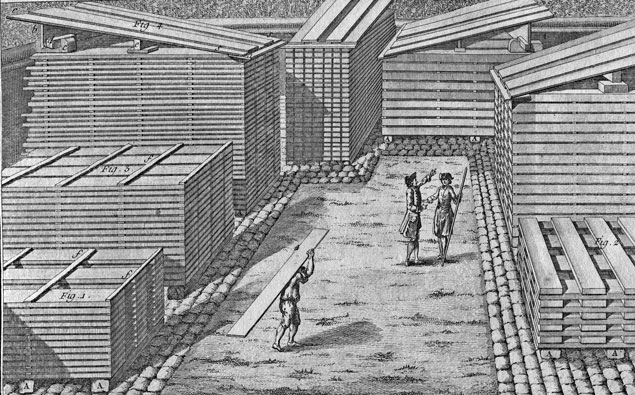

“The workbench is the first and most necessary of the woodworking tools. It is composed of a top, four legs, four stretchers and a shelf. The top is made of a plank or table of 5-6 thumbs thickness by 20-22 thumbs in width. For its length, that varies from 6 to 12 feet, but the normal length is 9 feet. This bench is of elm or beech wood but more commonly the latter, which is very solid and of a tighter/denser grain than the other….

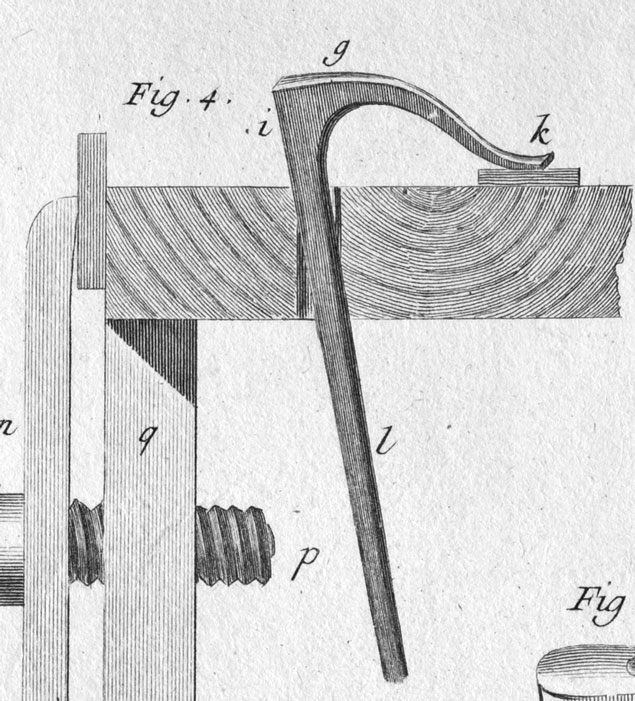

“…The planing stop should be 1 foot in length at least, and be of very hard and dry oak so that it can withstand the mallet which one is obliged to hit it with to make it move…

“…The legs of the bench are of hard oak, very firm, 6 thumbs in width by 3-4 in thickness….

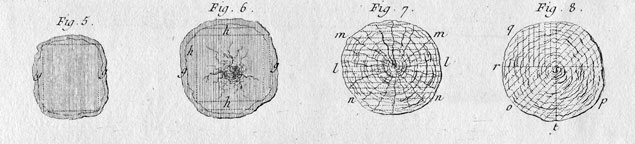

“…One should observe also to put the heart-wood side of the bench on top because it is harder than the other, and if the wood experiences dimensional changes, it is more likely to change from this side rather than shrinking from the other side.”

To be certain, Roubo discusses the seasoning of lumber for furniture, but as anyone who has dried thick slabs can tell you, those are an entirely different animal from lumber used for tables and chairs.

While reading the rest of Roubo’s writing on furniture, a section on kitchen tables stuck out. Here is some of the text from Plate 253:

“The top of kitchen tables is made of a thick plank of beech in which you assemble the legs whether by tenon and tail like the woodworkers’ workbenches, or even with double assembly, which is about equal. In either case, it is good, for cleanliness sake, that the assemblage/joinery not pass through the top (so that they [the tops] be easier to clean and straighten up as you are using them), but on the contrary that they have but two-thirds of its thickness, which is sufficient, always with the condition that they be assembled very exactly.

“Kitchen tables vary from 6 feet up to 12 and even 15 to 18 feet in length by 18, 24 and 36 thumbs in width, but this is very difficult to find without splits and other defects.

“The thickness of these tables varies from 4 to 6 thumbs and even more, if possible, the large thickness being necessary given that you flatten them from time to time, which thins it rather promptly.

“In general, the top of kitchen tables should be oriented in a manner such that the heart side is on top so that when the slab is moving [in response to dimensional/seasonal change], it can only move from this side, which you can remedy easily. What’s more, you can eliminate this problem, as least partly, by choosing the driest wood possible, which has but a very little reaction as a result.”

Here Roubo is saying to make kitchen tables like a workbench. And to use the driest wood possible. And to orient it heart-side up. Here’s another clue:

“Whether the kitchen tables be wide or narrow, it is good to place across the two ends some [leather] straps [it is a ligament from an ox, dried and hardened] attached above, which prevents them from opening, but restrains them, which is much better than putting there iron links, which, truthfully, prevents their opening, but which, when the tables shrink, splits them, given that they do not make allowance for this.”

The way I read this (and I could be wrong), is that you should cover the end grain with leather to restrict moisture exchange in the end grain. There are lots of ways to interpret this. One way would be: Leather can help keep a wet top from splitting.

In the next entry, I’ll discuss what I am going to do to answer these questions in my mind.

— Christopher Schwarz

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.