We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

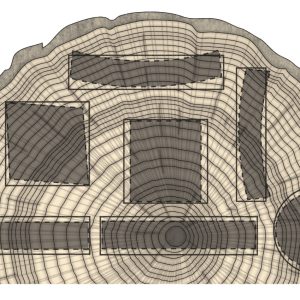

I built my Roubo clone frame saw many years ago after seeing a similar one in Colonial Williamsburg’s Hay shop. With my version, which is a closer approximation of the Roubo saw in both style and blade geometry, I attempted to improve on some of the slow cutting attributes of the Hay shop’s saw. Now some four years later, I’m realizing these saws really don’t work that well. They certainly aren’t a quick and easy tool for resawing. And producing hand cut veneer (below) is a feat of skill and no doubt specialty tooth-filing very likely beyond the capabilities and patience of normal woodworkers.

I just want to bring a few details to your attention:

1) The log in the picture really isn’t that large. And most of the cuts through the sap will very likely result in unusable material. If true, why would anyone make those cuts? Is it possible this picture is merely illustrating the concept and not an 18th-century snapshot of actual work? (btw: notice the toe-pointing first-position stance of these craftsmen – hard to believe any self respecting woodworker would stand this way, even if they are French. Got to be some artistic license here. We are brothers all.)

In general, when sawing thin stock, the saw cut will wander to the weak side. When I cut thin stock (or even rip a small amount from a board), I find a way to support that waste. Failing that, its always best to resaw in halves. I would have started these cuts in the center, then split the subsequent cuts.

Also, regardless of the tension placed on the blade, a thin piece of sheet metal cannot react to any torsion whatsoever. In use, these saws twist in the kerf, follow the path of least resistance, and are generally difficult to control.

2) Has anyone seen one of these in an English shop? I’m not talking felloe saws, the short frame saws made popular by Windsor chair makers years ago (who I suspect exaggerated their resawing capabilities). The large frame saw we have seen images of always come from French sources. Remember that French craftsmen didn’t generally have English panel saws in the 18th-century.

My experience is that resaws of 12″ or less are better, faster, and more easily handled with a coarse toothed panel saw. Resaws over 12″ are best handled at a mill.

3) My ham-fisted babel fish translation of Roubo went somewhat like this: When the work is small, [the cabinetmakers] do it themselves. Otherwise they send the work to the mill. (Isn’t that what I said my experience was above?)

Remember that 12″, 18″, 20″ resaws are what pitsaws were for. I think a good, motivated team could saw 1″ per minute. “Maybe faster,” says Roy Underhill. I can rip 1″ per stroke with a hand saw through 4/4 stock. Perhaps this many-times made public admission has set an unrealistic level of expectation.

I hate to produce a negative-sounding or discouraging post. But I feel strongly that I may have misled folks into thinking these saws are reasonable approaches to resawing thick material by hand. After four years of trying and refiling, I now believe they are not. Nor do I believe that historically they were fantastically productive tools.

One more word of caution: There are a lot of people making saws, filing saws, selling parts or kits of saws that really aren’t optimized for the intended job. To make saws well, you have to have done more than a few test cuts with them or asked one man’s opinion. Beautifully sculpted handles and shiny blades won’t help you saw dovetails for four or six hours. Likewise, there are many satisfied customers raving about saws that I don’t think work well. Though I would never want to be accusatory, I wonder how many folks are responding after some significant use of the product, or do they open the box, make a test cut, then post to a wood forum. Without taking a poke at anyone, beware.

My approach to designing and making hand saws (I’ve made many) was to make prototypes, sometimes many prototypes, and test them in real world conditions over a period of years. Let’s call this post the end of one of those test periods. I would not offer my version of this saw for sale because I don’t believe it would meet the expectations of woodworkers who have access to good quality panel saws. For the 18th-century French workmen, it may have been an improvement over what they had. For us, these saws are not.

100% honesty –Though I’ve always found a way around it (and never used one), I think a large resawing bandsaw looks like a good substitute for a pit saw operation. I would not be embarrassed to have one in my “hand tools only” shop. I doubt it would be the end of my hand sawing days. And pit sawn lumber looks like band sawn lumber (except the pit saw marks are at a slight angle from perpendicular). In the same breath I make this uniformed recommendation, I recall my own advise to listen carefully to those with practical experience. I invite you to help your fellow woodworkers here and now. Can you resaw 16″ wide 8/4″ boards into 2, 3/4″ boards on a band saw? Do you need a special band saw, band saw blade, sled or outfeed rollers? What does it take to resaw wide lumber with modern machinery?

Last word: I apologize to those I’ve inspired to make these saws, and who later found out they didn’t work quite as well as I hyped. (No, I didn’t misspell “hoped”).

– Adam Cherubini

Check out Adam’s many, many projects and PDF downloads at ShopWoodworking.com.

Check out Adam’s many, many projects and PDF downloads at ShopWoodworking.com.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.