We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

A look at Ken Richards’ life in woodworking.

A look at Ken Richards’ life in woodworking.

After six years as a draftsman at Boeing—his first job out of high school—Ken Richards had enough money put aside to buy five acres and a barn in nearby Maple Valley, Wa., and he was ready for a career change. “Six years of sitting at a desk, in a room full of desks, in a giant building full of rooms full of desks—was enough to convince me the insecurity of unemployment beat the security of Boeing,” he recalls.

Drawn to woodworking, Richards got a contractors license to pay the bills and spent his free time building furniture in the barn, for family and friends. To keep his overhead low, he lived in an unfinished house on the property—essentially a basement with a roof on it, left behind by the previous owners.

Within five years, Richards was woodworking full-time in the barn and had his first piece in the Northwest Fine Woodworking Gallery in Seattle, a thriving retail space for beautiful contemporary work. His padauk wine cabinet sold quickly to a visiting couple from Florida, who were interested in ordering other pieces.

A couple of months prior to that in the spring of 1991, Richards was wiping finish onto his largest piece to date, a ceiling-high, 8-ft.-long walnut buffet for a client’s dining room.

The next morning, the barn, the buffet, and all of his tools and equipment were gone. “I missed some oil-soaked rags when cleaning up the night before and they spontaneously combusted,” he says. “Everything went up in flames.”

When the couple from Florida showed up, Richards was “covered with dirt, working in a ditch, and laying foundation forms for a new shop,” he says. His commitment to his woodworking career must have been obvious, because the couple commissioned a full dining set, plus two other pieces, and were willing to wait.

“There was never a thought about picking another path,” he recalls. “It was, ‘What do I need to do here?’ I started making ‘build’ and ‘burn’ piles, had the new building up in six months, and was back to work replacing the buffet.”

When his original barn workshop burned down in 1991, Richards built one for the future. It’s been a critical part of his success as a pro furnituremaker.

Rich Life, Modest Budget

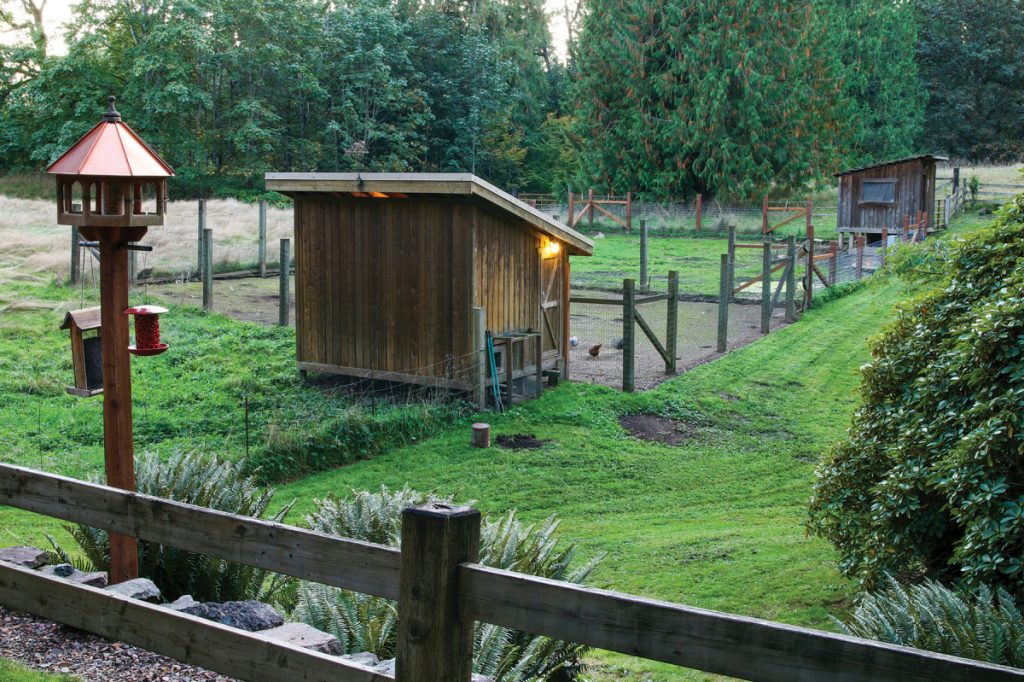

What Richards has created in the 27 years since is astounding. His furniture is a tour de force of fine woods, ornate detail, deeply sculpted surfaces, and meticulous craftsmanship, with recent pieces taking up to a year to finish. On the idyllic property he never left, he built a huge two-story workshop and an extraordinary home, both almost entirely on his own, each as personal and pristine as his furniture. Every fir beam, every charming shed and fence, he crafted it all, while raising chickens, cows, and the occasional pig for food.

Ken Richards is an example of how talented, determined woodworkers can live far beyond their bottom line. His formula: Buy a nice piece of land, stay on it, buy materials as you can afford them, build everything yourself (you’ll figure it out, and friends will help), and refuse to compromise your vision. “There’s a connection you get when you built something, that you don’t get when you purchase it,” he says.

Dream Shop

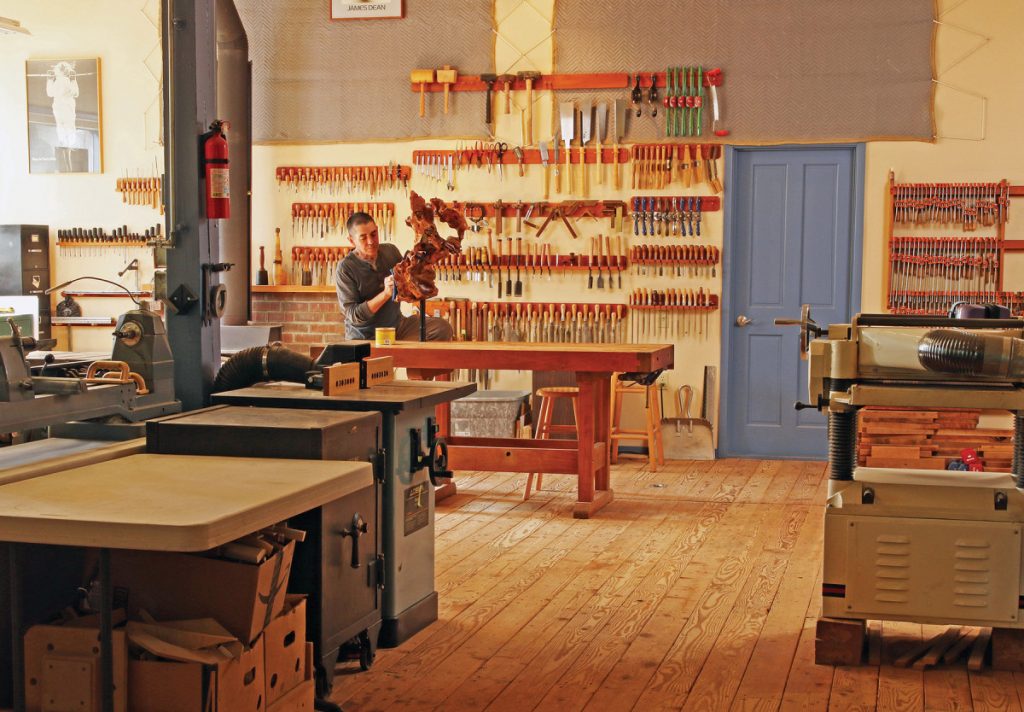

The fire gave Richards the opportunity to design a workshop for the future, a two-story building that houses lumber drying and wood storage below and a spacious 1,000-sq.-ft. workshop above, with a wall of windows bringing in a wash of natural light and an elevated view of the pastoral landscape.

Upstairs is a 1,000-sq.-ft. workshop with a wash of natural light, beautiful views of the property, tons of storage, and plenty of room for outfeed, infeed, and big projects.

“The old barn had very limited space for tools and wood storage,” he says. “The new one let me take my work to another level, building multiples and big dining sets. Setting up and working in a space specifically designed as a wood shop—rather than working to try to make an existing structure work—is a big difference.”

As Richards’ work transitioned from machine work to hand work, the shop got quieter, making room for another of Richards’ passions. To bring hi-fidelity music into the sunny workshop, he connected an audiophile stereo system to world-class speakers, which are suspended by chains from the ceiling and angled down toward his workbench. The tops of the high walls are draped with moving blankets to improve the acoustics. As a result, Richards’ CD collection sounds shockingly like live music.

As Richards’ work became more focused on handwork, he added an au-diophile stereo system to fill the silence, with world-class speakers and wall hung blankets making his CD collection sound like live music.

The dust collector and duct system is housed downstairs, keeping the shop quiet, with no hoses underfoot.

At the other end of the shop is the bench area, with Richards’ extensive hand-tool collection at the ready.

Richards’ built a clamping ledge into the middle of his bench, to accept standard bar clamps. It’s one of his favorite features.

The ground floor of the workshop houses two huge rooms for wood storage and a third lumber-drying, which have allowed Richards to take advantage of bargains and acquire world-class materials for his work.

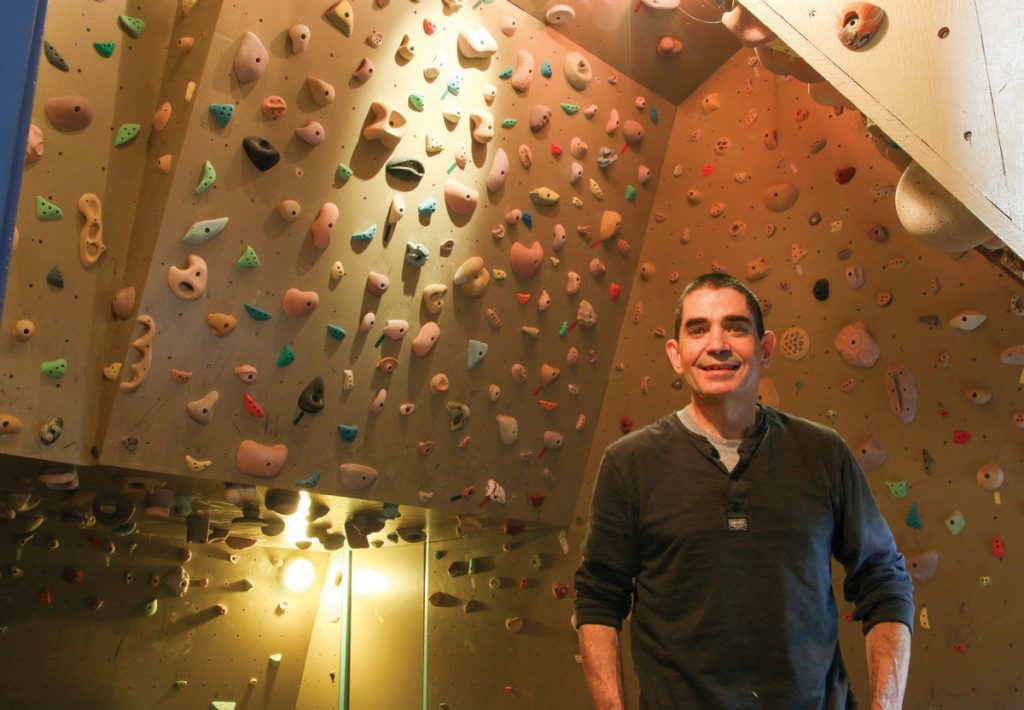

Behind the bench area is his office, which doubles as a climbing gym. Rock climbing has been Richards’ main pasttime for 20 years, providing exercise, relieving stress, and building friendships.

A House Built like Furniture

When the fire struck, Richards plans for a new house on the old foundation were put on hold, and he lived in the improvised basement house with his wife for another 12 years. Then he gutted the existing place down to the raw foundation, and built the house he had been dreaming about for years.

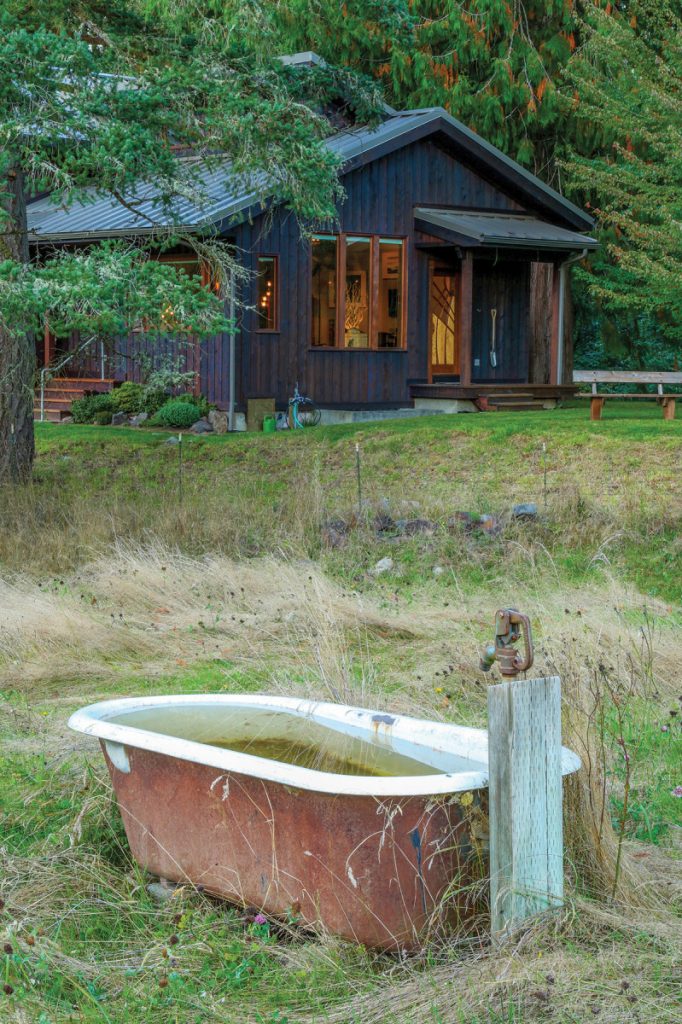

Richards lived in the foundation of this house—essentially a basement with a roof on it—for 23 years before he was able to build a full house above it.

Richards extraordinary home sits comfortably among the trees, crafted from native woods, with wide eaves and a wraparound porch. Like the workshop, it’s designed to fit his life, and sided with the same vertical cedar, finished with clear oil. Unlike the shop, the house feels almost like a museum, with gorgeous fir beams above, marble and maple floors below, exotic wood trim all around, and Richards’ furniture and art collection spotlighted by careful lighting.

The main floor is open, with a big stand-alone cabinet separating the kitchen and living spaces, with art objects displayed on one side and kitchen cabinets on the other. The second floor is a partial loft that houses the master bedroom, bathroom, a small library. The basement houses a lovely guest suite.

Exposed above both floors are timber-framed trusses Richards fashioned from clear, old growth fir, salvaged from submerged logs. The porch also has a timber-framed roof, this one from old-growth cedar, also salvaged.

The wraparound porch, wide eaves, and natural siding settle nicely into their Pacific Northwest surroundings.

By day, clerestory windows at the roof peak light the trusses and help the other windows bring in natural light. By night, the entire home—trusses, Richards’ furniture and sculpture, the display cabinet, and both floors—is illuminated with an extensive system of low-voltage lighting fixtures that he designed and installed.

The front door has curved panels and sand-shaded marquetry. The siding is cedar with a clear oil finish, just like the workshop.

After years of late nights and patient work, Richards is at ease on his five acres, feeding the chickens and ducks, grilling grass-fed steaks on the porch, and turning his woodworking career in a new direction.

Richards crafted the timber-framed trusses from clear, old-growth fir, and illuminated them with accent lighting and clerestory windows at the peak of the roof.

A large display cabinet divides the open floor plan. The floors are marble and maple, and the trim is a mix of afromosia, wenge, birdseye maple, quilted Western maple and imbuya.

Intentional lighting spotlight Richards’ furniture and art collection, which is arrayed around the room. On the left is a bombé chest, one of his earliest challenges. On the right is a breakfront display cabinet in ceylon satinwood, characterized by exotic woods and delightful embellishments.

Richards built the sheds and fences for the chickens and livestock he raises for food. An old bathtub waters the cows.

Design Process

While his work has recently turned toward sculpture, Richards is one of the Pacific Northwest’s most accomplished furniture makers and he has valuable lessons to share with pros and hobbyists alike.

The first is not rushing the design stage. Richards’ brainstorming process begins with a series of rough sketches. “Once I think I’m on to something, I start working on proportions and detailing with scale drawings,” he says. The third step is full-size drawings, which he tapes to MDF and props against the wall to get a better viewing perspective. A favorite trick for refining a design is “splitting a piece down the middle and trying different shapes, proportions or details—one version on one side, another on the other.”

This collectors stand, made from Nicaraguan cocobolo, is designed to display a collection of small, precious objects. Richards detailed the back as nicely as the front, so the piece will work in the open, as a room divider of sorts. (Courtesy of Ken Richards)

Drawings are just the beginning. “I make better decisions when a piece is sitting in front of me as a three-dimensional object, rather than a 2-D drawing,” he says. “So I find ways to mock up options with pieces of scrap, clamps, duct tape, whatever.” He also notes that designs look different when you walk away for a few days or more, let your subconscious go to work, and come back with fresh eyes and new solutions. “Procrastination can be a good thing,” he says.

Words of Wisdom for Would-be Pros

The main challenge for full-time woodworkers is finding clients who can pay for high-end work. In the beginning, Richards worked for friends and family. He was also lucky to have a wife with a good-paying job at an upscale restaurant. Many of his first pieces went to her customers.

After that, he had another lucky break. Nearby in Seattle was the country’s oldest and largest woodworking cooperative, the Northwest Woodworker’s Gallery, where Richards drew inspiration and connected with clients. It closed in 2016 but the website (https://www.nwwoodgallery.com) still promotes former members.

Once connected to clients, Richards tried to convey his passion and talent, telling them about the materials, process, and potential of an idea. “You have to become comfortable being around wealthy people,” he says. “Go in with confidence—as an equal. I’m not a salesman. I walk them through my portfolio and tell stories. There’s no hard sell.”

Once they were committed, he treated clients well, welcoming them to visit the shop, sharing photos of the work in progress, and always over-delivering in the end. As a result, many of his clients became lifelong friends and patrons, purchasing multiple pieces through the years and sustaining him through the market meltdown of 2008.

A related key to success, he says, is shooting excellent images of his work and creating a powerful portfolio, both in print and online. For today’s pros, he also acknowledges the importance of an active social-media feed.

Part of treating himself as an equal was estimating his time on a project, pricing it accordingly, and taking payment in a series of 25% deposits. The first gets a project on the schedule, the next is paid when drawings are approved, another comes when he’s halfway done building, and the last 25% is payable upon delivery.

Some of Richards’ pieces feature extensive marquetry. He built this dining set in narra for a home with a lakeside view, sculpting the chairs flawlessly, for beauty and comfort. (Courtesy of Ken Richards)

As for what to build and how, there are many paths, he says, each with its tradeoffs. “I’m at one end of the spectrum—making high end, one-of-a-kind art pieces. But I know folks who live very rewarding lives doing simpler designs they can produce efficiently on a limited-production basis. Some have developed specialties—shoji screens, for instance.”

This sideboard, in quilted makore and holly, was Richards’ most technically challenging project to date. He carved the curved parts by hand from thick lumber. (Courtesy of Ken Richards)

Regardless of their personal path, he sees common traits in successful pros, or “survivors,” as he calls them. “They have a strong inner drive to create, they work hard, and they operate their businesses with a high level of integrity. If you are not strongly driven to do this work—strictly for the personal rewards that come from creating things and being your own boss—then it’s probably not for you. If you do have that drive, it can be a very rewarding lifestyle.”

He adds with a wry smile: “A supportive spouse with a regular paycheck helps a lot.”

A New Direction

A couple of years ago, Richards stopped looking for furniture commissions and started making pure sculpture on spec. “I decide the price when I’m done and there’s no time pressure,” he says. “It’s a reward for paying my dues, and developing a toolbox of hand skills.”

The design process is also more free. “I start with a fuzzy idea, start playing with the wood, and see where it goes,” he says.

With sculpture Richards often lets the wood dictate the design. At the heart of this piece, called “Tranquility,” is an extraordinary slab of maple, with spalting that stops in a distinct line.

Richards made “Glory” from 40 hard-carved piece of ceylon satinwood. It includes a pedestal with built-in lighting.

Richards’ work has turned lately to sculpture. This piece, called “Smoke,” is made from an olive root burl that he pulled from a friend’s free pile.

He’s not sure if he will be successful as a sculptor, but Richards is giving himself three years to develop a portfolio and find out. Furniture tends to be seen as craft, not art, and the hope is that the new work will find different galleries and venues, and draw prices appropriate to fine art. “I’m still following my heart,” Richards says. “In that way, it’s not any different than the past.”

Asa Christiana is the former editor of Fine Woodworking magazine, now living and working in Oregon. Follow him on Instagram @buildstuffwithasa.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

What a great story and amazing person/artist/craftsman Richards is. Very inspiring. Well written too!

Great Article! Awesome story! Amazing Pictures! Loved it.

I dont know how one can recoved from a burned down workshop and come back so strongly.