We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Dan’s wood of choice for the Torii table (read part one of the story here) was Paulownia, a fast-growing tree that is both soft and strong, and that has been part and parcel of the remarkable Japanese woodworking tradition. I wrote about this light color and silky-looking wood a few years ago in a story about my friend Takuji Matsuda who among other things builts Kiribakos – special boxes for holding Buddha statues made from Paulownia.

Dan’s wood of choice for the Torii table (read part one of the story here) was Paulownia, a fast-growing tree that is both soft and strong, and that has been part and parcel of the remarkable Japanese woodworking tradition. I wrote about this light color and silky-looking wood a few years ago in a story about my friend Takuji Matsuda who among other things builts Kiribakos – special boxes for holding Buddha statues made from Paulownia.

Because Paulownia trees are one of the fastest-growing species in the broad-leaf family (the tree matures and is ready for harvesting at the super young age of ten years old) attempts have been made to commercially grow it beyond its native Far East habit. One such growing attempt took place in Israel but unfortunately did not bear fruits, as the trees did not flourish as expected. In the process of consolidating the plantation, Dan and the farmer agreed that in exchange for helping in cutting down the trees Dan will receive a few logs. After milling the logs on site, Dan had enough lumber for a few projects.

The Design

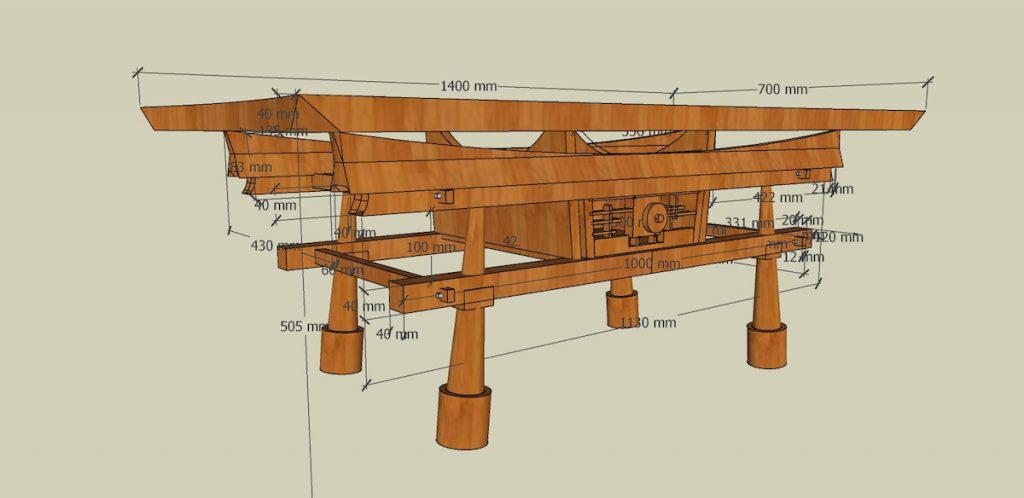

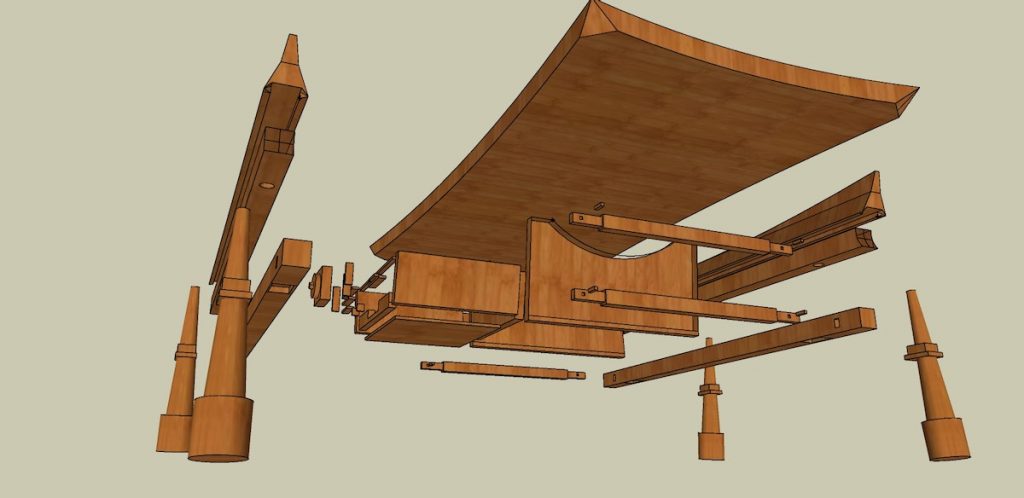

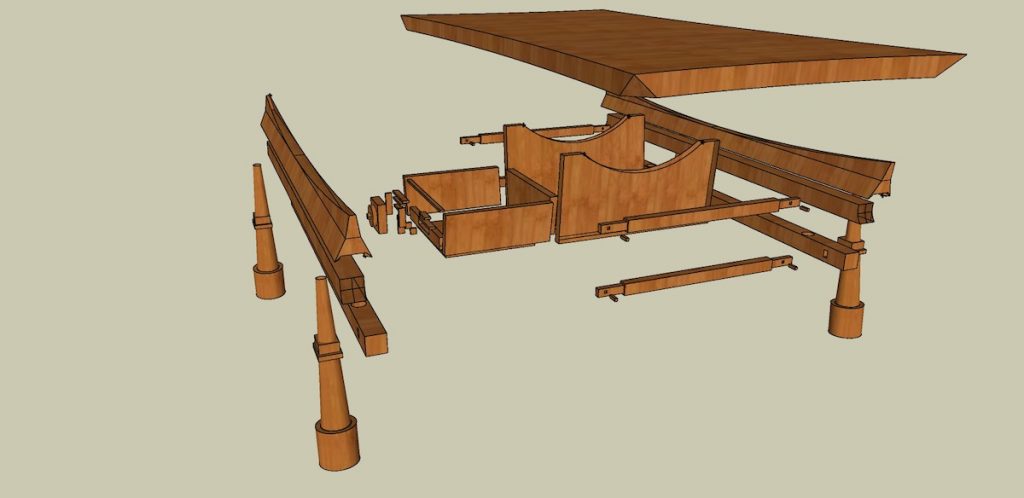

Dan based his project on the design of the Torrii gates. His trestle-looking table is made of a wide top that is supported by two Torii gates that are connected together by a group of rails. In the middle of the structure resides an encapsulated drawer compartment consisting of two flanking panels. These panels provide additional support for the top. Most of the table’s parts are connected together via through-tenons and locking wedges or other interlocking joinery. This allows the table to be assembled or disassembled and if needed compactly stored away. Using the tried and true locking joinery technique – which is so prevalent in Japanese traditional architecture – adds both beauty and historic context to the piece. On top of the esthetic focal point that these pronounced no-glue connectors provide, they are also remarkably practical and could be re-tightened as needed to secure the structure should seasonal wood movement loosen the joints.

Dan choose a joinery technique that bestows the table with stressless expansion and contraction during seasonal changes.

The Top

After sawing the log into boards Dan laid up a few of them and arrange them edge to edge in preparation for glue-up. Notice that the middle board has elongated dimples along its middle. These interesting-looking cavities are actually the tree’s pith and are one of the visual hallmarks of the Paulownia tree. After gluing the boards together Dan hand-planed them and then cut the top to shape.

The top’s composite support beam/apron (Kasagi and Shimagi)

The tabletop is supported by an inverted arched lintel that is made of a beam duo: a long and convex beam called Kasagi and underneath it a shorter beam (Shimagi) that is connected to the Kasagi via a tongue and groove joint.

Dan while shaping the spire cross-section geometry of the Kasagi.

Laying out the convex arc of the Kasagi.

Planing the arc.

Next time: Turning the legs and more work on the highly sophisticated structure.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.