We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

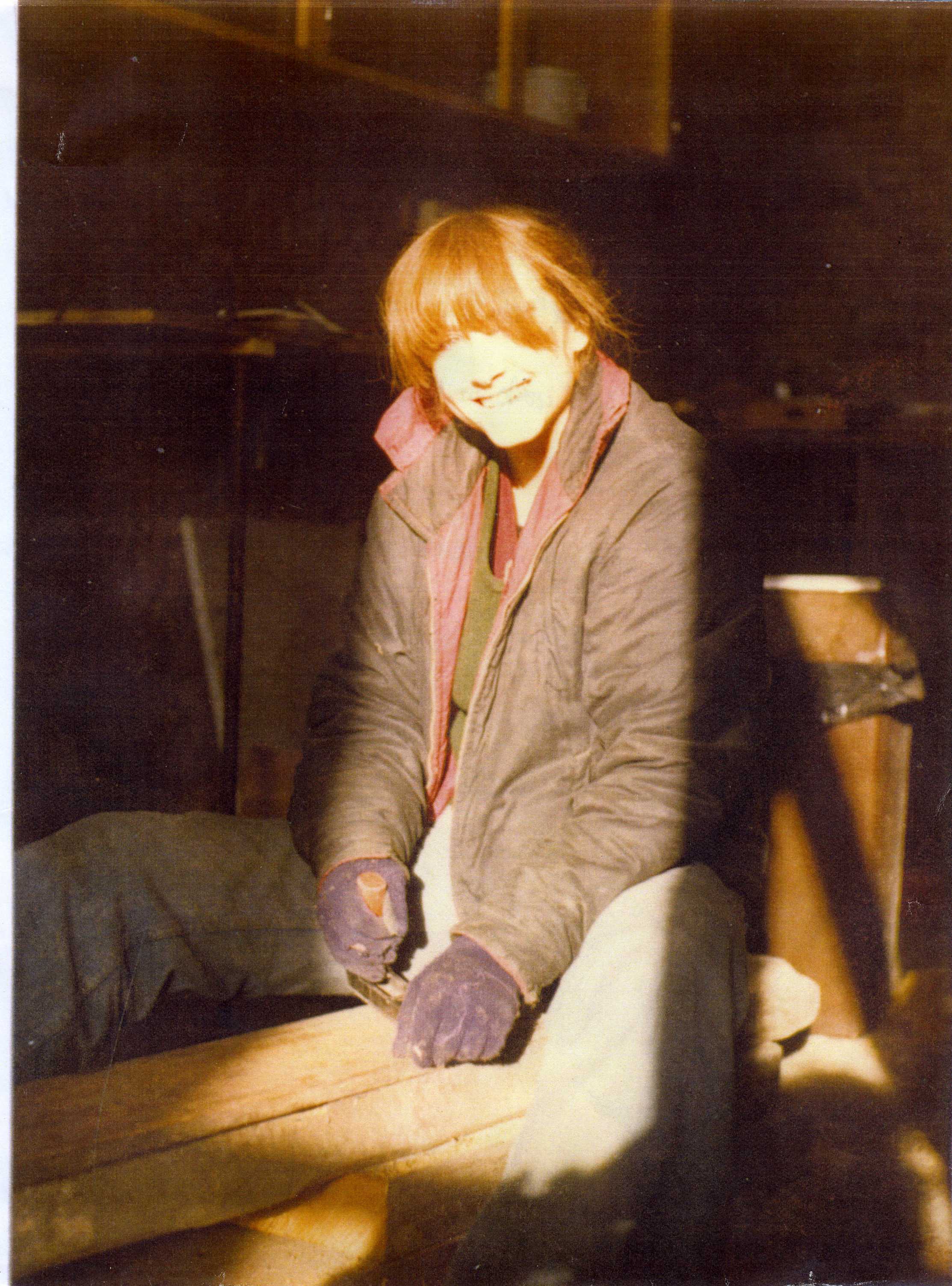

Covered in coal dust, east London, circa 1975

Further Reading: The More Things Change, the More They [Change]

In 1996, about a year after I started my business, an acquaintance contacted me to ask about having a bookcase made. When we met to discuss what he had in mind, he showed me a sketch and gave me rough dimensions. I called the next day with my price. It was probably something like $1200; I don’t remember. “You can’t charge those kinds of prices!” he told me. “You haven’t paid your dues.”

What the $^% is he talking about? I wondered. I had a decade of professional cabinetmaking under my belt at that point, having worked in two furniture and cabinet shops in England, followed by a business in the States that made flashy furniture for offices in Boston and New York.

“You’re not known around here,” he said. “Until you’ve made yourself a local reputation, you’ll have to take whatever your customers are willing to pay.”

As it happened, I was desperately in need of income, so I told him I’d build the bookcase for the insulting $250 he offered, explaining that for that kind of money I’d have to build it out of 2-by-12 joist material. He agreed, and that was the bookcase he ended up with.

***

I haven’t given much thought to the culture of paying dues until a few recent occasions, when I’ve been struck by how this dimension of woodworking culture—at least, the culture of professional furniture and cabinetmaking, outside the art furniture world—has changed. It’s sobering to reflect on your responses to an interaction with someone who just recently entered the field and realize that you’ve become that seasoned curmudgeon who rolls her eyes—if only figuratively, in my case (because, unlike my erstwhile customer, I do my best to avoid flagrantly insulting others). In every case I follow up with a serious dose of self-critical grilling as to the origin of my would-be eye-rolling response. Here’s the first part of the explanation, a quick look at the longstanding culture of paying dues.

Another day on the miserable jobsite in east London, 1976

The culture of dues paying originates with the Latin verb debere, from which the word debt is also derived. At its simplest, it means “should”; it’s about obligation, whether moral or institutional. Go a step further to English synonyms for dues, which include tolls and tributes–the latter, in this case, connoting the infamous Roman tax, rather than the way we use the word today, i.e. to connote an honor or accolade.

As with some other kinds of dues, there are instances where the obligation can be imposed from outside. (For those interested in etymology, this makes perfect sense, given the root of “obligation” in the Latin ligare, from which we get “ligature”; all of the words derived from this root, including “religion,” involve the notion of binding or being bound.) My erstwhile customer was taking advantage of my newness in town; in effect, he was extracting a tribute (or dues) because he was in a position to take advantage of my circumstances.

Until recently, the culture of paying dues was also widely internalized as an ethos. It was fundamentally about respect: for those with greater experience, for those whose custom makes it possible for us to earn a living, and for the traditional skills of our field—the last a kind of respect that made it unseemly to assume the identity of a trade, whether “furniture maker,” “cabinetmaker,” “carpenter,” “mason,” or what have you, unless you had worked your way through some type of recognized training in your trade, followed by earning your living in the field, starting on the ladder’s bottom rung. (While on that rung, a now-highly respected craftsman of my acquaintance found himself, circa 1982, dispatched to the hardware store to buy some elbow grease). Today, in contrast, it’s not uncommon to find “furniture maker” in the byline of a writer who makes his or her living as a research chemist or attorney.

At my second furniture and cabinetmaking job, 1986

My next post will contrast this culture with some of what I see today, taking a hard look at what’s been lost and what’s been gained.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

This reminds me of the 5th episode of ShopTalk Live, wherein Asa Christiana pointed out the paucity of background checking in place for self-named reliable sources of woodworking skill and instruction. What a fun time that was.