We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Sam Maloof’s sculpted rocking chairs are iconic, so much so that his name is synonymous with that furniture style. The timeless design is striking—light, strong, curvaceous and quite comfortable—made with a combination of machine and handwork. Beyond his furniture, there’s much inspiration in Maloof’s way of life and reasons for doing the work he did. I return to this passage from his autobiography (Sam Maloof: Woodworker) time and again, reflecting on the 1957 Craftsmen Today conference.

“There I first met Walker Weed, Wharton Esherick, Art Carpenter, John Kapell and Tage Frid. Bob Stocksdale I had met previously, but this meeting cemented our friendship,” Maloof writes. “What we all had in common was that we were doing what we wanted to do. None of us was a conformist. None of us wanted to be tied up or bound. I believe all of us were seeking spiritual well-being in what we were doing. We were not using our work as a means of avoiding responsibility in a material sense.”

I reached out to Mike Johnson, who worked side-by-side with Maloof for more than three decades and continues to build his designs, to learn more about the Maloof chair joint.

“Sam’s early chairs from the 1950s and 60s used a very simple joint that was made by taking the side seat rails and clamping them outside edge to outside edge, then boring a hole centered so that when the rails were unclamped it left a half round socket where a lathe turned leg would then be made to match,” Johnson says.

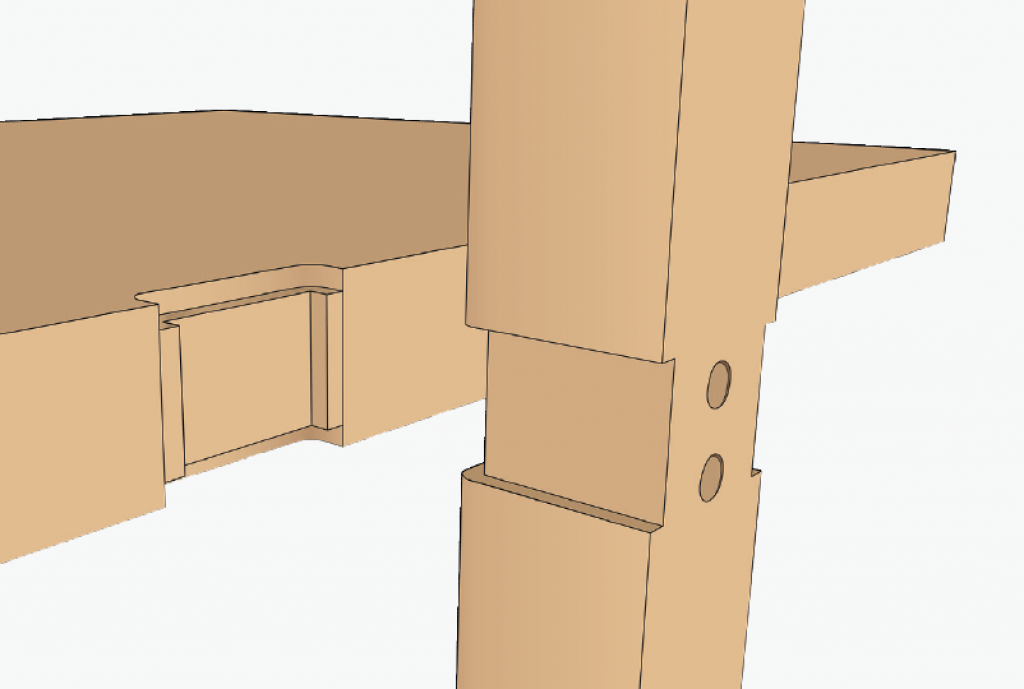

“Just shortly after the wood seat was introduced in 1970— prior to that all seating pieces were upholstered—Sam started experimenting with the leg to seat joints. Ultimately he settled on using 1/4″ rabbeting bits to cut shoulders that the front and rear legs could interlock and be supported with.”

After the chair is glued up, the handwork begins, blending the machine- cut joints into the form with rasps and files.

“With as much gluing surface and interlocking quality of the joint, it is arguable as to whether or not the screws used to reinforce the joint are necessary. But Sam would use them anyway, because he wanted to build pieces that would stand the test of time,” Johnson adds. “Early Maloof pieces had their screw holes plugged with the same wood the chair was built from. Sometime in the late 1970s Sam started using contrasting wood—mostly ebony— as a design element.”

After all, as Maloof said, “Why go to all that trouble of making a beautiful joint only to hide it?”

The Maloof chair joint is cut in five steps. First, cut a 2″-wide, 1/4″-deep dado in the side of the chair seat. Then, use a rabbeting bit to cut 1/4″ recesses at the top and bottom of the joint. Mill the mating leg 2 1/2″ wide (the width of the joint), round over the inside corners of the leg (to match the round left by the rabbets), then cut a 1 1/2″-wide, 1/4″-deep dado on the three mating faces of the leg to match the opening. Once the pieces are fitted, the leg joint is blended and shaped by hand.

A Bit About Mike

Mike Johnson and his wife, Joanne own and operate Sam Maloof Woodworker, Inc. Their son, Stephen is Mike’s shop assistant, while Joanne serves as business manager. Mike, now in his 38th year with the Maloof organization, has been granted the exclusive licensing agreement to produce Sam Maloof furniture. Mike and Stephen work in Sam’s original workshop, building furniture and accessories as well as doing restorations on Sam’s early work.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.