We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

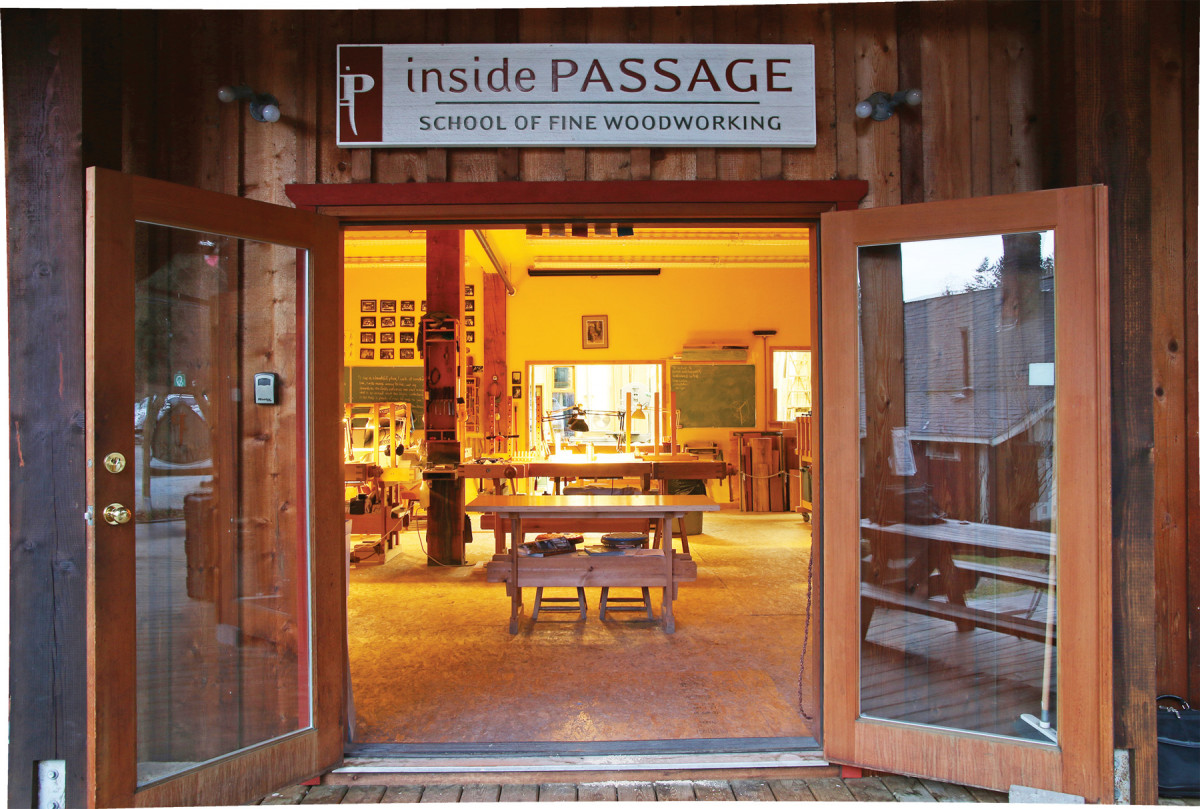

Met with open doors & a smile. At Inside Passage, the doors are open 24 hours for students. The school’s founder, at center, is Robert Van Norman; at left is his wife, Yvonne. At right is Caroline Woon, an exceptional former student, originally from Singapore, who ran the afternoon sessions at the school.

A gifted teacher preserves and shares the legacy of James Krenov.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of Popular Woodworking Magazine

To reach the Inside Passage School of Fine Cabinetmaking, you head northwest from Vancouver, B.C., leaving behind the glass-towered city to board the ferry at Horseshoe Bay. Pull up your collar and stand alone on deck as the vessel threads between snow-capped mountains to tie up near the little town of Roberts Creek. For more than a decade now, students from 37 countries have made this brief but beautiful journey, navigating a piece of Canada’s vast coastal waterway to pursue an inner path, one marked out by the late cabinetmaker and educator James Krenov.

The school’s founder is Robert Van Norman, a gifted maker and teacher who forged a deep friendship with the older man. When Krenov’s eyes began to fail, he so believed in Van Norman’s venture that he donated his workbenches, hand tools, machines and entire archive of photos and slides to the school.

The school’s founder is Robert Van Norman, a gifted maker and teacher who forged a deep friendship with the older man. When Krenov’s eyes began to fail, he so believed in Van Norman’s venture that he donated his workbenches, hand tools, machines and entire archive of photos and slides to the school.

“I know the people there,” Krenov said at the time. “I like what they are doing and I like very much the way they are doing it. The emphasis is on hand skills, not primitive methods but efficient skills. Work that can be traced to the maker, the hand, the eye and the heart.”

Unable to be at the school when it opened but eager to help, Krenov acted as an adviser and gave weekly lectures via speakerphone, which Van Norman recorded for posterity. Today those recordings are a core part of the curriculum, accompanied by slides from the archive.

On the Friday I visited, I sat with students in the bench room, with morning sun flowing in, listening to Krenov’s high rasp cover the fine points of solid-wood construction, laughing together at his wry asides, as if he were still with us.

Independent study. Students spend the bulk of their week working on their own in the beautifully appointed shop, with assistance from instructors or other students as they need it.

It got quiet when the old master moved from the how to the why: “It’s just something that you want to do, do with your hands, your mind and your heart. What we need is more heart in our work. Just live the way you want to live.”

Later that morning, Van Norman visited each bench, checking progress and offering guidance. “Robert has this ability to gently help you diagnose your problem and help find a solution, without hurting your self-esteem,” said first-term student and “recovering lawyer” Dave Rush. “He is an incredible teacher.”

Later that morning, Van Norman visited each bench, checking progress and offering guidance. “Robert has this ability to gently help you diagnose your problem and help find a solution, without hurting your self-esteem,” said first-term student and “recovering lawyer” Dave Rush. “He is an incredible teacher.”

With four terms running simultaneously – just a few students in each – the rest of the day was a dance of quiet work and collaboration, with students of different levels helping and supporting each other. Occasionally Van Norman gathered a group to his bench for a lesson targeted to their term.

The lectures live on. Once a week, students gather to listen to lectures Krenov gave to Inside Passage students before he died, paired with slides from his archive, many of them unseen outside the school.

It’s a formula and environment he has refined each year since 2005, and the results are undeniable. The student work coming out of this little school is among the best worldwide. Considering that many students start with no experience, the results are even more impressive.

How the school came about is just as unlikely, a story of one life mirroring another and a legacy carried forward.

Van Norman Finds His Calling

Vintage & storied. Some of Krenov’s original cast iron is employed at the shop. The yarn doll sits over the throat plate when the machine is not in use, reminding students to lower the blade before walking away.

Abrupt and standoffish to some, Krenov could be just as supportive and kind to those with the passion to do great work. He must have recognized that spark in the young man who called him from Saskatchewan in 1987.

Working as a shop teacher for at-risk kids, Van Norman had discovered “A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook” (Linden), Krenov’s collection of profound, personal reflections on working wood that inspired a generation of woodworker-artists. When Van Norman cold-called him, the renowned Swedish-American educator was still at the helm of the woodworking program he founded at College of the Redwoods in Fort Bragg, Calif., but not too busy to encourage a stranger.

Following his role model, who had trained with Carl Malmsten, a founder of Scandinavian furniture design, Van Norman found his own local teacher, a German cabinetmaker in Alberta. Although the commercial cabinetshop was off the path Krenov describes in “The Impractical Cabinetmaker,” Van Norman stayed three years, soaking up what knowledge he could and supporting his young family. Finally, he summoned the courage to go it alone, taking commercial jobs at first but soon making only speculative work, starting with a rocking chair that sold for twice what he expected.

Robert and his ever-supportive wife, Yvonne, who ran a house-cleaning business, lived the life of the self-employed for more than a decade, when a 1998 fall left the cabinetmaker with a serious back and leg injury and chronic pain. Once again, he turned to his mentor for the answer.

In the foreword to “A Cabinetmaker’s Notebook,” Craig McArt recalls Krenov – still in his small workshop in Sweden – musing about teaching when he got too old for “lifting heavy planks” and other rigors of full-time furniture making. “A light went off for me,” Van Norman said.

By then, he had been talking regularly with his far-off friend for 12 years, and Krenov invited him to College of the Redwoods to meet face-to-face. Once together in Fort Bragg, they hatched a novel plan. Already a masterful woodworker, Van Norman would apply, with the stated purpose of becoming an educator in the mold of his mentor.

After graduating, Van Norman took a variety of teaching jobs, most notably at Rosewood Studio, a woodworking school now in Perth, Ontario, founded by a former student of Robert’s. But still, the pure path eluded him. To find it, Van Norman would have to start his own school, just as Krenov had done.

Beginner-friendly Instruction

Two from the teacher. This double rocker was the first custom piece Van Norman sold.

Along their journey, Robert and Yvonne had lived and worked in Vancouver, B.C., and they wanted to return west to start their school close enough to the city for student access but far enough to find solitude. A friend suggested Roberts Creek, a tiny town on the “Sunshine Coast,” a gorgeous but less-traveled place accessible only by ferry.

Sitting by the woodstove in the Gumboot Cafe, the town’s only eatery, Van Norman knew he’d found his new home. It took months of permitting and rezoning and a second mortgage on their house, but in 2005 the school opened in a beautiful building in the tiny town center, surrounded by the restaurant, post office and a handful of small shops. It was just as Van Norman had dreamed it: a roomy bench room and fully outfitted machine room, with high ceilings, tall windows and space for 10 students, in a place Krenov would have loved.

The wenge armchair is his version of Vidar’s Chair.

With a network of former students, Van Norman was able to fill classes from the beginning, and he and Yvonne finished raising their kids in a small homestead a few hundred yards up the road. Living without a car these days, they walk into the next town to buy groceries and take the bus home.

Distinguishing the school from College of the Redwoods was never a problem. Location helped, as a number of students would come from Canada, but there were other factors. For one, Van Norman was willing to take beginners, designing a first term, Impractical Studies, in which students build a small wall cabinet called “Wabi Sabi” and are introduced “to a way of working, not to make a living, but an approach to the work, and to life,” Van Norman said. And the small class sizes mean there is never a lack of individual attention.

Also, by the time Inside Passage was born, Krenov had retired, and as new teachers and administrators had arrived with new ideas, the program inevitably evolved – still wonderful, but not the pure path Van Norman could offer.

Inside Passage also offers shorter programs than its California cousin: a series of four 11-week terms that can be taken in one year or spaced out as life permits.

Mentor & student. James Krenov (left) and Robert Van Norman met in person in 1998 at the College of the Redwoods.

Being small means being flexible. Inside Passage recently admitted a student plagued by debilitating migraines, who could not promise to be there every day. Keith Lewis was just finishing his first term when I visited, and he was smiling every time I looked over. “This is the best I have felt in a decade,” he said, crediting the meditative work for keeping his headaches at bay. “[The school] is one of the nicest-feeling places I’ve ever been, warm and supportive, and way more inspiring than I even expected.”

“The school gives you the time and space to become so immersed in what you’re doing,” said Leanne Fleming, who is finishing her second term. “People come with no experience and Robert takes the time to make sure every student is successful.”

Group lesson. Van Norman gathers first-term students for a demonstration on lock mortises.

Senior students were just as passionate. “I was looking for a school that worked in a tradition, not just a trade school,” said third-term student Tim Andries.

During the weekly show-and-tell, held every Friday afternoon, fourth-term student Refael Greenblatt, at the school by way of South Africa and Israel, spoke seriously and profoundly about wrestling with the construction of his piece. “The design started with a spark, a fixed starting point, as Krenov says. In this case it was the curve of the doors.” From there he designed the joinery by look and feel. “Ask yourself, ‘What can the wood do?’” he suggested. “It’s been quite satisfying to get back into this deep sort of work, to be in this zone again.”

Show & tell. Students gather at the end of each week to report on their progress and lessons learned. Part of the school’s formula is students of all levels sharing their frustrations, victories, advice and inspiration.

On Friday night the school held a reception for a past student, Juan Carlos Fernandez, who ran a successful shop in his native Venezuela before coming to the school, and now lives and works in Roberts Creek with his wife, also an artist. “I came here to get my master’s in cabinetmaking,” he said. “I loved being here at the school. You get so much feedback and information from your fellow students. I learned sharpening and hand tools. Those were a mystery to me. Everything is so considered in this work, even the back panel that never gets seen. And it’s worth it – loving things to the last detail.”

If You Go

One-on-one. Instructors make the rounds to help with problem-solving, drawing out answers rather than giving them.

If you are ready to set sail along the Inside Passage, here are a few more facts and thoughts. The small school is usually full, so you might be wait-listed for a bit. When you arrive, you’ll find that materials are provided, as are hand tools for those who are lacking. Doors are open 24 hours, and nights and weekends are favorite times, cementing strong bonds between students.

Regardless of skill level, everyone starts in Impractical Studies, where they are introduced to the school’s tools, techniques and philosophy. Rush was grateful for the first-term help he received. “It takes a village for me to build a cabinet,” he said during the afternoon show-and-tell, drawing a big laugh.

Upward Spiral is next. Here students build one of five pieces made by Krenov in the late 1960s. “By removing the design component, students are able to focus on developing their skills as craftsmen,” Van Norman said. “In his three years at Malmsten’s school in Stockholm, Jim did not build pieces of his own design, but pieces that were designed by Carl,” Van Norman said. “When he set up his workshop and began composing, he began to make his own music.”

Krenovian inspiration. Refael Greenblatt, a fourth-term student, cited a pair of Krenov’s curved doors as the jumping-off point for his own cabinet on stand.

The third term focuses on one specific project, Vidar’s Chair, designed and made by Vidar Malmsten, the son of Carl Malmsten. “While Krenov did not make chairs, he liked this one very much, and he did make beautiful stands for his cabinets,” Van Norman said. “This exercise prepares our students for that, by focusing on grain lines, shaping and compound-angled joinery.”

Third-term project. Here, Tim Andries works on the back splat for Vidar’s Chair. “This [the school] was exactly what I had been looking for without being able to articulate it.”

Last comes Composing, where students still work from one of Krenov’s pieces, but only as a starting point. “There is no set design; it is more of an evolutionary process. The wood speaks, and we do our best to listen. Using sketches and mocking up, student and teacher work together, looking at each step and making decisions along the way,” Van Norman said.

Coming Full Circle

A cabinet comes home. After Krenov died, one of his cabinets came on the market. Van Norman’s wife bought it sight unseen. It turned out to be one that he helped Jim glue up at College of the Redwoods, and one of the last he built.

Wherever you turn at the school, you find the life and legacy of James Krenov. His words, pictures and methods are everywhere. His beautiful vintage machines are tuned and whirring in the machine room. Lyrical cabinets stand by the workbenches in various states of completion, built by new hands. And he is alive in Van Norman, a quieter, gentler version of his hero.

Guarding the legacy. In his own small shop, just up the road from the school, Van Norman has the rest of Krenov’s machines, his entire archive of slides and prints, plus Krenov’s own workbench and one from the school run by Carl Malmsten.

Just up the road from the school, in the Van Normans’ small sitting room, is a cabinet that completes the circle. Before Robert left College of the Redwoods, Jim called him over to help glue up a cabinet-on-stand, one of the last he completed. Years later, after Krenov died, Yvonne got an email about one of his cabinets being for sale in Texas. It was the same piece Robert and Jim had glued up in 1999.

I have read James Krenov’s words, seen his work in photos and edited articles by his fellow teachers and best students, but it wasn’t until I met Van Norman, spent time at his school and ran my hands and eyes over that lost-then-found-again cabinet that I really understood the revolution Krenov started. Maybe it took a devoted disciple to follow the path to its end, in a little town along Canada’s vast Inside Passage.

Website: Visit the school’s website at insidepassage.ca to find out about classes and instructors, and to see more student work.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.