We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Smooth design. Karl Holtey’s remarkable No. 982 smoother is a masterpiece of precision design and engineering that would make NASA blush. This tool features boxwood totes.

The best rationale for these ultra high-end tools might not be what you think.

Editor’s note: This article originally appeared in the December 2015 issue of Popular Woodworking

Over the past decade, I’ve made somewhere approaching a couple hundred custom handplanes, both for my own enjoyment and (since 2010) as my full-time occupation. I’d like to take some time here to tell you why every woodworker needs a custom handplane in his or her shop.

But I can’t do that.

The truth is that most woodworkers need a modern “super” plane in exactly the same way my 6-year-old son needs a jet pack.

So let’s get that settled right off the bat. Offerings from Lie-Nielsen, Veritas, Clifton and Old Street Tool have taken the modern handplane into already-rarefied levels of performance. Properly set up and tuned, those companies’ tools far exceed the needs of almost any woodworking shop.

For that matter, local flea markets and auctions are sources for classic Bailey pattern and wooden planes, most of which can be tuned to serve a shop’s needs with just a little care and attention.

On top of that, there is a whole range of vital handplanes that have no justifiable alternative in the custom plane world. Scrub and fore planes, the jack plane, fillister and plow planes – not to mention moulding planes of all variety.

And yes – this is my standard sales pitch.

Now that I’ve shot my business in the foot, let me tell you why I remain committed to tools I’ve just seemingly relegated to the land of unicorns and altruistic stockbrokers – and why some woodworkers still have good reason to desire custom handplanes the way my son pines after Spaceman Spiff couture.

First, allow me to debunk a few myths about the appeal of high-end custom planes.

Myth: Shelf Jewelry

Style & substance. Brese Plane’s “Winter” series tools combine top-flight engineering and design with custom patination, giving them the stunning aesthetics of a modern classic. This is a Winter Panel plane with desert ironwood totes.

One of the most basic assumptions about custom planes is that their main appeal is their appearance – that they’re made not so much for users as collectors.

In my experience, while the aesthetics certainly count for a lot, any modern maker will tell you that when exhibiting at events and shows, it’s not the seeing that ends with a commission. It’s the using.

A refined Brit. My Daed Toolworks index planes are an outgrowth of classic British infill thumb planes, refined for dramatic ergonomic improvements. Shown here are African blackwood infills.

My entire marketing strategy, soup to nuts, consists of “try the plane.” There’s something about how the tools work that simply calls out some woodworkers. (More about how they work in a bit.)

Myth: Dampened Spirits

Moving sculpture. Wayne Anderson’s (Anderson Planes) unique designs include a wealth of artistic touches and careful ergonomic details that make the planes as lovely to use as to behold. This panel plane features rosewood infills.

Another common misconception holds that infill planes in particular have an advantage over other designs because the wooden bed dampens vibration. This one is just plain nonsense – and in fact, is 100 percent opposite of reality.

This myth won’t last a second when one considers the woods most commonly used and desirable for planemaking. Rosewoods, boxwood, ebony – almost to a one, these are woods valued for their hardness, stability, low elasticity and high density.

In fact, nearly all these woods are considered tonewoods, and are primarily prized for their ability to carry vibration, not dampen it. This is not an accident.

Myth: Mass Appeal

New approach. The Sauer & Steiner K13 is a radical ground-up rethinking of the traditional panel plane. This one has African blackwood infills.

There is a surprisingly prevalent notion that high-end planes are especially effective because of their high mass, and the corollary improvement in momentum of the planes in use.

This is a fairly recent (and oddly enduring) idea. For the overwhelming majority of written woodworking history, and for the vast majority of modern woodworkers, unnecessary weight is considered 100 percent detrimental to plane function.

Let me say this as clearly as possible: All else considered equal, less weight is almost always more desirable in a smoothing plane.

Finishing First

At this point, I think it’s important to acknowledge that the vast majority of custom-made planes are unabashed one-trick ponies. They’re made to do one thing – and one thing only – extremely well: perform final smoothing. Period.

Because they don’t have to meet a wide range of purposes, they can be fastidiously optimized for this one task, and the maker can tune a plane to suit a specific set of needs and circumstances.

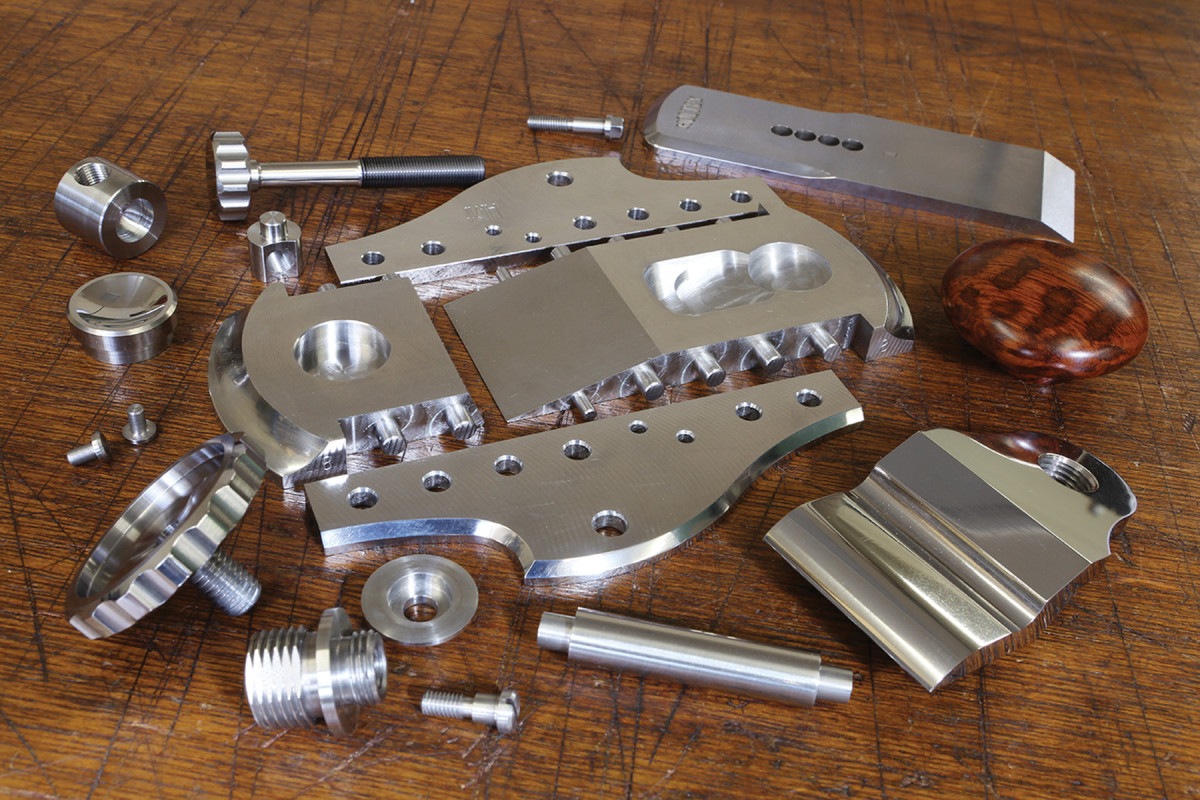

For most of the planes in the custom world, the materials costs are on the order of perhaps 10 percent of the total price of the plane; the overwhelming majority of the cost is in the labor that goes into making the tool.

When you buy a custom plane, then, what you’re paying for first and foremost is the technical skill and extensive time from the maker. From a performance standpoint, what you’re getting is ground-up technical expertise and tuning from someone who eats, sleeps and breathes these tools all day, every day.

The standard features of a well-made and tuned plane – flat soles, careful bedding, fine mouth etc. – are all taken to the highest levels here.

One aspect that I think is underappreciated, though, is the remarkable degree of feedback that the best custom planes convey. This (at last) is the “how” in “how they work” that attracts so many people at a gut level – and to my way of thinking, that might be the most important performance advantage of custom-made tools.

Communications Specialists

Strong tradition. Made with bronze sidewalls and a steel sole, the traditional dovetailed construction on this Sauer & Steiner XS No. 4 coffin smoother becomes readily apparent.

To explain what I mean by feedback, let me divide smoothing technique into two categories that I see over and over again at trade shows, gatherings and in my own shop.

Technique One is what I call planing for speed. In this method, the woodworker is almost throwing the plane through the wood – often making good use of a plane’s inertia to keep it in a cut, and to move very quickly and smoothly through the chore.

This approach is good when one has a lot of ground to cover, and when wood selection has been carefully considered. Straight-grained and relatively figure-free woods are incredibly forgiving when approached with a well-tuned sharp tool.

I also think this accounts for much of the fascination with mass – because as the woods get harder (think African and Australian timbers) it is tempting to trade on the increased momentum a heavier tool can bring to bear. This is the exception to the rule that lighter is better for some woodworkers.

Secured forever. On the No. 983 block plane, Karl Holtey mills integral pins into the sole pieces to mate with the sidewalls. When finished, they’ll be peined to secure the assembly permanently, forming an incredibly rigid and powerful structure.

Technique Two is what I refer to as planing for sensitivity. It comes into play in work where the work surface is not straight-grained, is highly figured, or where tear-out would be more than inconvenient – it would be catastrophic.

Consider high-end furniture, where a premium is often placed on highly figured and interlocked-grain woods such as crotch mahogany, quilted or bird’s-eye maple – not to mention expensive figured exotics.

Planing these materials often requires a degree of finesse that is pointless in most handplane work, and this sort of work benefits from a dedicated tool made to carry out the task.

Bedded down. The thick mouth block on my Daed Toolworks coffin smoother is riveted and peined directly to the plane’s sole. The matched wooden portion of the bedding will be secured to the sidewalls with peined through-rivets on assembly.

Planing for sensitivity relies on the woodworker’s senses to adjust the angle, speed, direction and skew of the plane to compensate for shifting grain, and smooth the surface to optimum effect – and to avoid the devastations of tear-out.

Sight and hearing both come into play in this arena, but more than anything else, the talented woodworker familiar with his or her tool is in this case literally feeling the changing grain of the board and compensating on the fly.

Real steel. The bed extension in this Brese Winter Smoother is steel, and riveted directly to the sidewalls of the plane.

That heightened sense of physical contact with the wood is where the highly tuned custom plane shines, because the construction and operation of the tool is intimately concerned with providing information to the woodworker’s senses – particularly the tactile sense.

What exactly is it about these planes that makes them such good communicators?

Monolithic Baby

Unmoved. In order to mitigate the possibility of wood movement, Holtey uses a pair of full-depth brass posts to serve as the bed extension of his A1 plane.

Above all else, the greatest structural strength of today’s custom planes is due to the methods and designs used to build their shells. There are two common methods used to join the sidewalls and soles, but fundamentally, each ends in a shell that’s cold-forged into a single structure.

On more traditional infill planes (where the shell’s interior is entirely filled by timber), the sidewalls and sole are usually joined by a double-dovetail joint, while more modern designs often use a series of peined bolts or pins for joinery.

In either case, once fully assembled and peined, the results are often invisible and end in a singular structure which is irreversible and extremely strong and rigid.

The structural integrity extends also to the bedding. The most common bedding solutions include a thick “mouth block,” which is generally joined directly to the sole with peined through-rivets. The bed is extended from the mouth either with wood or metal, which is in turn through-riveted directly to the sidewalls.

Stripped & Streamlined

The art of work. Subtle details, including texturing, chamfers and graceful curves, not only look beautiful, they have a significant impact on ergonomics. The Art Deco-inspired profiling on this chariot plane by Wayne Anderson is visually stunning, and the texturing gives the wedge and bun improved grips.

To carry information from the cutting edge to the user’s hand, vibration must be very carefully transmitted through a certain path, and in custom planes, that path is usually much simpler than a modern Bailey-style plane.

With no adjustable mouths, moving frogs and often no adjusters at all, there is simply much less opportunity for the lost rigidity and feedback that carry information to the hand.

Handled with Care

Hidden strength. In the traditional infill technique, the tenon of the handle extends all the way to the sole, as on this Sauer & Steiner K18. After fitting and shaping is done, two steel pins will run through the sidewalls, surrounding infills, and tote tenon for a stiff, permanent and invisible fit.

The greatest loss in feedback transmission in most Bailey-pattern planes comes from the totes.

I couldn’t venture to guess how often I’ve seen loose totes on old Stanley and Millers Falls planes – but I can tell you that it’s epidemic by any standard.

Even when properly secured, the inclusion of a tote is often one of the primary points for reduced feedback in the plane if the mating and securing aren’t carried out extremely well.

Where totes are employed, most modern planemakers mitigate the issue by attaching totes using methods that are much more secure and substantial than line-manufactured planes.

The technique of securing the tote is often one of the most interesting parts of a plane design – with many makers using extreme ingenuity and engineering to accomplish the task.

Unhandled with Care

It’s a Brese. This Brese plane uses custom-made two-part bolted brass lap hardware to secure the rear tote invisibly and securely.

A remarkable range of custom planes are designed with no tote at all, returning to once-ubiquitous coffin smoother designs, or using wedges (or even the blades themselves) as handholds to provide as much feedback as possible.

Generally, the tote is most important not on the cutting stroke, but on the return stroke – and it is usually only really necessary on larger and heavier tools. Many smaller designs, then, forego the tote.

Simple sensitivity. There’s no tote like no tote. Coffin smoothers are one of the oldest and most effective forms for sensitive planing. (This one is my design.)

The coffin smoother, a fixture of pre-industrial cabinetmaking shops, is still a thriving design in the custom-plane world, and with just a single chunk of wood between the blade and hand, its simplicity makes it a spectacular conveyor of feedback.

In fact, for many small planes I design the blade itself to be used as a handle – giving what I feel is the ultimate signal path for feedback.

Summing Up (Up & Away)

Blade runner. On smaller planes such as my M2, I often make use of the blade itself as part of the handling strategy for the most direct tactile feedback possible.

As I’ve said, the pitch for custom planes from a need or cost-benefit stance is a non-starter. They’re simply not significantly better at core performance than today’s best mass-manufactured planes. Their highly tuned, feedback-friendly and lovely designs, though, will still always have appeal to some woodworkers.

There’s no denying that for me – or rather, my son – there is no objective need for a 1,600-horsepower impulse-propulsion jet pack. The minivan, bicycles, skateboards and the occasional plane ticket get us everywhere we will ever need to go. But that doesn’t mean that I won’t be saving every penny for the day the Google jet pack gets released. I will.

Because for me (I mean my son), the appeal of a cutting-edge device that raises the hairs on the back of my neck in use – or even just lets me drop water balloons on my neighbors – is well worth the expense.

Now please – turn the page before I start ranting about what I spend on wood. PWM

Raney is an infill planemaker and woodworker at Daed Toolworks (daedtoolworks.com); his shop is located near Indianapolis, Ind.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.