We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

Good bones. Learn to see the form to understand a design’s hidden structure.

Look for the ‘bones’ to observe how form defines design.

It happens during almost every furniture design workshop. At the start of day two, a carload of students shows up 20 minutes late.

One would think they’d be embarrassed, but instead they burst in all giggly and excited. Then the story spills out. They were on their way with plenty of time until they noticed a courthouse, library, cathedral or theater across the street. With a few minutes to spare, they piled out for a closer look. It was then they realized they had new eyes. Instead of seeing just an old building with stone walls and wood doors, they saw for the first time what the original designer saw – the shapes and patterns once hidden, now alive again for those who can see.

I’ve yet to hand out detentions for these latecomers. Truth be told, once you begin to see like a designer, it’s hard to resist the pull of a great building or a masterful piece of furniture. So what does it mean to see like a designer? What do designers see that most mortals don’t?

Order Out of Chaos

Squint. Close your eyes nearly shut until the details blur to see the bold shapes in this design.

It’s not like a designer’s eye doesn’t see the same things we do – details such as joinery, wood grain, and color. But those are all separate items that, by themselves, are each but a puzzle piece. If anything, a designer’s eye sees details with greater depth and understanding because each is seen in the context of the entire design. In a way details can be roadblocks to actually seeing a design, like standing too close to a large painting so that it’s impossible to take in the whole masterpiece. So let’s step back and look through a designer’s eye.

The first and most important thing is to take in the form. A form is usually a simple shape or a combination of simple shapes that lies invisible just beneath the surface. A form gives bones to the design, whether through a bold and simple geometric design or a complex exterior hiding elusive shapes beneath. It can be as simple as a circle or square, or a combination of several shapes, such as rectangles, ovals or triangles.

One way to find the form in a piece of furniture is to gaze at it and squint your eyelids almost shut. Squinting will blur the details and allow you to see the underlying form. Try this squinting technique on something that’s over-the-top in ornament or decoration. You’ll see past all the surface noise to what lies below and may be surprised to find something unexpected.

Once you see the overall form, it opens the door to unpacking a design. You get a closer look at how it breaks down into simple smaller shapes, such as doors and drawers or even open space.

But it’s important not to think of what you are looking at as doors, drawers or open spaces. Instead try to just see squares, rectangles and circles – simple shapes. And once you identify the smaller shapes, step back and compare them to both the overall form and each other. Depending on how complex the design is, you might also be able to identify smaller sub-shapes. Ask questions about how these simple shapes relate to the whole. Are they laid out symmetrically? Are rectangles sized differently to play off one another?

Lines & Good Bones

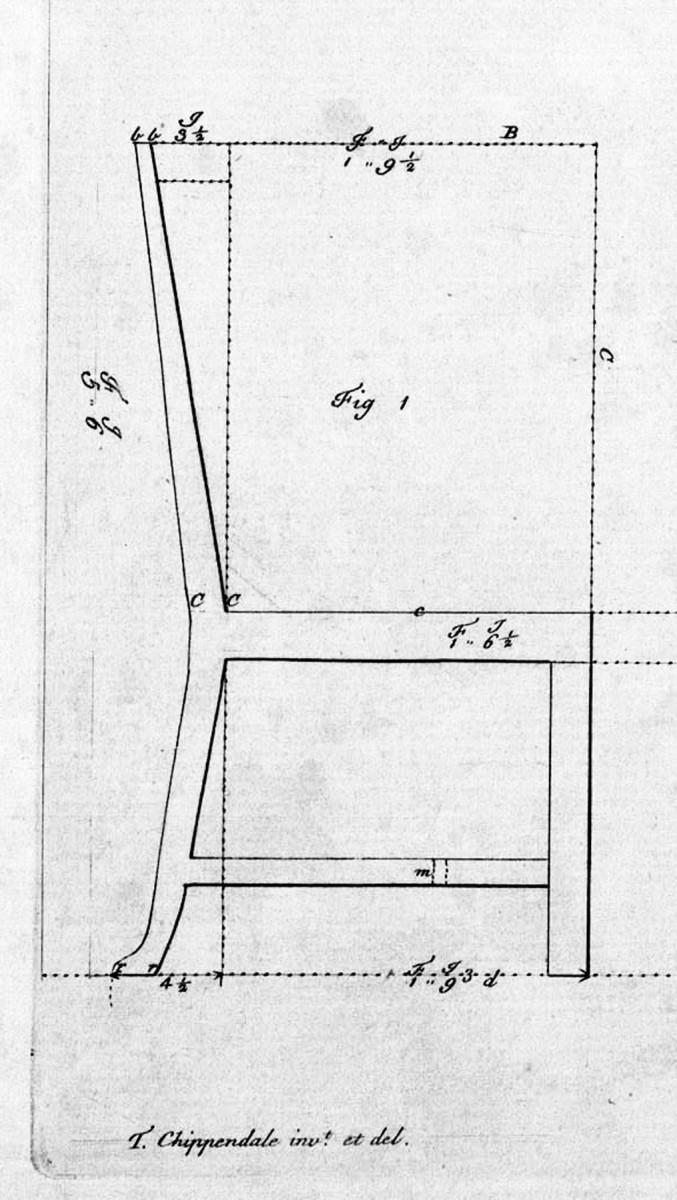

What’s inside. Tilted parts, such as this chair back and legs, are easier to visualize when viewed against an inner form.

People often say that a piece of furniture has nice lines. That might sound cliché, but there really is something important about a design’s lines. Lines reveal how the actual boundaries of a design relate to the inner form.

Returning to our analogy of bones, lines are like skin and muscles that echo the skeleton, or form, beneath. Our design might be built around a rectangular cuboid form, but the actual lines of the piece could curve in relation to that inner form. And knowing this can go a long way toward understanding and seeing curves. If you can compare a curved line to a straight line on the underlying form, your eye will have a reference to gauge the curve’s sweep. All of a sudden, a curve that was just floating out in space gets a visual anchor to help us see it.

But it’s not just curves that relate to a form. A design can have angular lines springing from an internal form – a chair design with lines that are neither true vertical nor horizontal, for example. Yet a designer’s eye sees these lines in relation to an inner form.

Our modern industrial approach uses degrees to measure the amount a line is angled. But if you think about it, using degrees is just a mathematical way to describe a sloped line. What a designer’s eye seeks out is the way lines or borders relate to the vertical or horizontal planes in an underlying form. Degrees are helpful when setting up a machine for a cut, but they’re less important than the ability to see how angled lines relate to a form.

No Turning Back

There is a downside to flipping the switch in your head that allows you to see underlying forms in a design: Once you begin to pick out forms, you can’t un-see them. You’ll gain a greater understanding of why certain designs are appealing and why some are downright awful, and you’ll become more of a curmudgeon about what you like and don’t like. But I think that’s actually a good thing.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.