We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

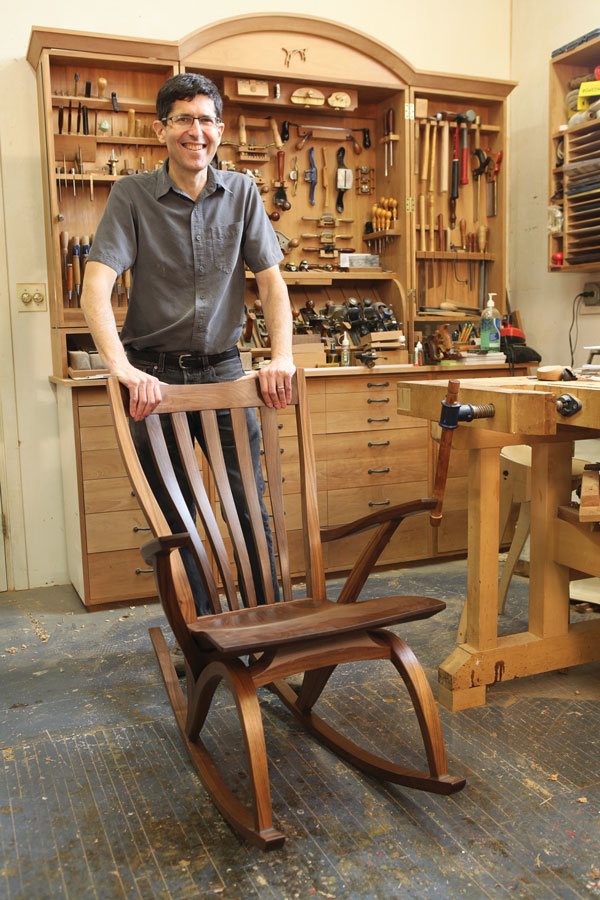

All kinds of music. Jeff Miller embraces street music and chamber music. Traditional design and modern curves. Hand tools and modern machinery. The results speak for themselves, as shown here in this walnut rocker he recently designed and built.

A former musician brings an improvisational skill to the craft.

by Christopher Schwarz

Somewhere between street musician and the symphony orchestra, between an 18th-century hand woodworker and a contemporary designer, is Jeff Miller, a Chicago furniture maker, teacher and author who defies every pigeonhole. In fact, if given the chance, he might just redesign that hole to better fit the pigeon.

Miller’s shop and showroom on West Lunt Avenue says a lot about the craftsman that’s difficult to define. The space is a former post office in a neighborhood with deep roots in the migratory history of the city. After fulfilling its traditional federal role, the post office became a bowling alley, and now Miller glues up his chairs, tables and casework while always being conscious as to whether he is working in the lane or in the gutter.

“You see that red line?” he asks, peering through the countless glue drips on the floor. “That’s a gutter. I’m not so sure about the floor there. The lanes, however, are solid.”

This balancing act – between solid and ephemeral, old and new, traditional and funky – is the best way to describe Miller’s work.

In fact, it’s something that strikes you as you walk into his showroom. Right beyond the front door is what looks like a drop-leaf handkerchief table – a traditional 18th-century form. Yet Miller has tweaked its cabriole legs by adding some hard angles so the table looks like it might leap up and devour you. He calls it the “Spider” table.

“There is something about the old stuff that compels me,” Miller says. “There’s a reason those designs endure.”

Yet Miller has never been satisfied to simply copy traditional designs and call it done. Every one of his designs seems to change a bit with each iteration. Though Miller was trained first as a classical musician, his designs seem at times more like jazz, which evolves through both constant practice and performance.

New tradition. Miller’s “spider” handkerchief table has traditional lines that have been altered for modern homes. Note the cabriole legs with their hard arrises.

Musical Roots

Miller was born in the Bronx in New York City in 1956, and his family soon moved to Westchester County, N.Y. He attended Yale University with vague ideas of studying biology, but he soon became immersed in studying music.

He got his master’s degree at the Eastman School of Music in Rochester, N.Y., then immediately took a one-year job as a trumpet player with Singapore’s newly founded symphony orchestra.

When he returned to New York, Miller started life as a freelance musician, which could mean anything from filling in with a chamber group to playing as a street musician in front of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

All the while he was working as a musician, however, Miller was also building furniture. During a semester off from college he had gotten a taste of woodworking while working in the shop of a luthier.

Then Miller landed a chamber orchestra job in Chicago. The job didn’t work out, and so Miller hung out his shingle as a furniture maker.

“For no sensible reason I started a furniture business,” Miller says. “There was very little skill but a whole lot of gall.”

Miller was about 26 years old at the time and was firmly grounded in both Mission and Shaker styles. Yet he always tried to make each piece his own. He’s continued that for more than 20 years.

“I’ve always tried to keep growing, to keep pushing and refining ideas,” he says. “Some of the stuff I am working at now I was just beginning to work with years ago.”

In fact, though Miller calls upon traditional forms, they are sometimes tricky to see under the layers of changes he has made year after year.

His refinements come from observing the human form and from watching how people sit in his chairs – a point that he emphasizes several times in one conversation. In fact, as he mocked up his latest rocking chair he assaulted anyone who came into his shop to sit in his prototype and tell him how it felt.

And even after he finished that chair (which was comfortable and gorgeous), he lived with it for a while then had it apart on the day I visited his shop. He wanted to change the slope of the seat.

Tweaked machinery. An SCMI table saw is at the heart of Miller’s shop. Note the shop-made blade guard (which he never removes) and the sliding fence, which Miller modified to satisfy himself.

Teacher & Writer, Too

In addition to constantly growing his design skills, Miller decided to take on writing and teaching, too. He’s written some wildly successful books, including “Beds” (Taunton Press). And he’s written the book that is considered the standard when it comes to contemporary chair design: “Chairmaking & Design” (Linden). And he’s been teaching classes in his shop since 1996. Now, he’s also now embarking on his most ambitious book ever.

The book, which doesn’t yet have a title, takes a musician’s approach to learning woodworking. It will focus on teaching the basic body motions that are then assembled into skills that lead to good craftsmanship.

“The crucial thing is you need to understand about how to use your body,” he says. “You need to understand how the tools work, plus how the wood works and behaves to make a mental model. You work your way from the ground up. That’s the way it is done in music. In woodworking, nobody wants to do that.”

Hand Plus Power

When it comes to tools, Miller embraces all the options, from vintage to new and from electric to hand-powered. In his shop he has some fancy Incra jointer/planers next to an early 20th-century Jones Superior Machinery 36″ band saw with wooden wheels that he restored.

He is a devotee of bent laminations, yet he prefers planing to sanding. He usually chooses spokeshaves over belt sanders.

“So there has always been a mix of tools,” he says. “What I find more and more is that some of these designs are not possible without hand tools. There are little things that you cannot do by machine.”

And that’s what makes Miller’s work special and enduring. It’s contemporary, but it has roots in tradition. It is guided by Miller’s hand, yet he developed the designs after observing how others used his furniture over the years. And it is built using power tools to save time and hand tools to make it perfect and unique. He’s a full-time furniture maker who also insists on writing and teaching, which then influences his work in the shop.

Massive iron. Tipping the scales at 1,275 pounds, this Jones Superior band saw has wooden wheels that Miller trued up using a router jig.

Like everything that happens in Miller’s shop, every action helps him tweak or improve everything else, from his designs to his teaching style.

“You have to be able to make the stuff,” he says. “When you have students, you understand what needs to be said and what people need to hear. That enables the writing – you have to be clear and to know some things in immense depth. And all these things feed back into the work.

“Everything reinforces everything else,” he says. PWM

Chris is the editor of Lost Art Press and the author of “The Anarchist’s Tool Chest.”

From the February 2012 Issue

Editor’s note: As Chris mentions above, Jeff is a teacher and author as well as a woodworker. You’ll find his book “Chairmaking & Design” and his latest book, “The Foundations of Better Woodworking” and his video companion to the book, in our store.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

![Bringing the 1955 Crescent Band Saw to Life! [Video]](http://www.popularwoodworking.com/wp-content/uploads/bfi_thumb/dummy-transparent-olcy6s63it1p9yp7uhusjas7c8kahafrhg9su7q9i0.png)