We may receive a commission when you use our affiliate links. However, this does not impact our recommendations.

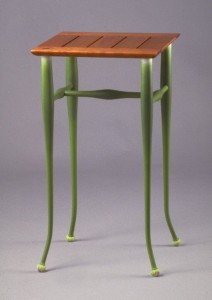

One of the pieces invited by the Cumberland Furniture Guild's upcoming exhibition on "Origin and Inspiration" is this little side table, which features legs and feet inspired by onion blooms.

Recently I had the privilege of serving as one of the judges for an upcoming furniture exhibition of the Cumberland Furniture Guild, a group of mostly Tennessee furniture makers (full disclosure: I’m also a member and on the board the Guild.) Having been on the maker’s side of the “judging” process, I know that submitting a piece you’ve made to any setting where judging is involved – like a furniture show or exhibition – is intimidating. Having been on the judging side as well, I also know it shouldn’t be.

For those of you who are curious about how the process works, it’s always similar to the process I went through today. The judges sit around a computer or screen and look at submitted images of furniture. None of the judges know who built which pieces, and, to be honest, don’t really care. The goal is to put together a collection that best represents whatever group is being judged and any prescribed theme. For this exhibition, called “Inspirations and Origins,” slated to run at the Customs House Museum in Clarksville, Tenn., from Aug. 10 – Oct. 28, 2012, we were asked to consider three basic concepts as we studied the pieces:

1) Workmanship

2) Artistic Inspiration

3) Did the maker meet or exceed his or her artistic goal.

Each judge graded the pieces on a scale of 1 to 5, and each judge has his or her own standards. But judges – for this show and any reputable one – are chosen to represent a variety of viewpoints. Candace Adelson, Ph.D., Senior Curator of Fashion and Textiles at the Tennessee State Museum, weighed in with wide-ranging expertise that covered everything from upholstery production to the historical lineage of certain designs. Kim Brooks, who, with her husband, owns the Finer Things gallery in Nashville, Tenn., and has shown contemporary furniture pieces for years, brought vast experience in adjudication and curatorial work of both fine art and fine craft. On this particular jury I was, at least in part, the “fellow maker,” and part of my charge was to point out the technical prowess required to build a given piece.

For Craig Nutt, a fairly literal interpretation of onion blossoms made a handsome set of table legs. . . when turned upside down and carved from wood.

The differing viewpoints definitely lent themselves to judging the collection of furniture we saw. To point 3 above: Aside from the workmanship of a piece, you also have to judge a piece on its own terms.When one judge commented that a certain design was too simple, I was able to point out the mostly concealed but impressive joinery involved. When I was ready to skip past what seemed a pedestrian design that was a little too modern for my tastes, a plethora of fine details were pointed out – the closer I looked, the more I liked it. And while I can’t guarantee that this is always the case, it’s the way a jury is supposed to work.

But putting your work out there is a step I encourage all makers to take. Whether you build furniture professionally or as a hobby, you’ll learn a lot by simply going through the process of getting a piece truly “finished” for judging. And if your work becomes part of an exhibition, interacting with a wide cast of people about the things you make will prompt you to ask questions about your designs and work that you may not have come up with on your own.

So if you enter a piece to jury, what’s the worst thing that could happen? They could say no. Even that shouldn’t be discouraging: Perhaps you submitted a blanket chest to a show that was flush with them, or your chair to a particular juror who thought your ball-and-claw feet were reminiscent of Philadelphia when he favored Boston. Even that shouldn’t bother you too much. It’s happened to everyone. Just as every good writer has thrown away a drawer full of rejection letters, I’ve never talked to an accomplished furniture maker who hasn’t been turned down for numerous venues. That said, I’ve never heard any of them claim that going through the jury process was anything but a help to their work.

If all else fails, blame the juror and laugh it off. I once had a judge tell me that a wall cabinet didn’t make it into a show because the top board – unseen unless the roof blew off the building and you were looking down at my piece from a helicopter – didn’t feature continuous grain on both sides as the other three corners did (evidently he not only got a ladder, but also failed to realize that boards don’t grow in a loop that circles back on itself).

East Tennessee chairmaker Curtis Buchanan was invited to show a design that mixes the Windsor-style chair he usually builds with the chairs he teaches others to build as part of the GreenWood Project.

But those things seldom happen. So, my advice: Enter. You’ll likely get in, and/or learn something along the way. If all else fails, do as I’ve done and explain it away with vitriol. I’m sure there was something else the judges disliked about my piece (I could have pointed a few out myself) but by honing in on the wrong-headed I moved on. I also worked harder on my next piece, aiming for something that no judge could turn down. (I can aim, at least.)

We saw a beautiful array of work at the competition, and I learned a thing or two along the way that I know will echo in my own work. Studying the work of others, the successful and the not so, is something every woodworker should do. A good place to start is with well-established designs like those found in books of reliable, time-tested designs: “Furniture in the Southern Style: 27 Shop Drawings of Furniture from the Museum of Early Southern Decorative Arts,” by Robert W. Lang and Glen D. Huey; “How to Build Shaker Furniture,” by Thomas Moser; and “Greene & Greene Furniture: Poem of Wood and Light,” by David Mathais are all filled with fine examples. And don’t forget to take a walk through your local museum and historical homes-turned-museums – most are furnished with antiques and replicas from the area where you live.

I’m curious, what have your experiences entering shows and exhibitions taught you? And if you don’t enter, I’d love to hear why.

Here are some supplies and tools we find essential in our everyday work around the shop. We may receive a commission from sales referred by our links; however, we have carefully selected these products for their usefulness and quality.

I suppose if someone entered their piece in a contest it’s OK to judge; after all that is what the maker is looking for. However, I view furniture as a functional piece and furniture as art as two different things. A chair that is a beautiful piece of art but is uncomfortable is, to me, worthless as furniture. It is interesting that the three criteria you noted for judging did not include functionality, why? Personally, I would not judge furniture as art unless it was also functional. A piece that is beautiful to look at but non-functional is not furniture, it is only art no different that a painting. Art is in the eye of the beholder and is therefore difficult to judge. I’ve seen art pieces in museums that I would have called trash but then I’m not an art connoisseur. So bottom line, furniture should be judged first on woodworking skill, then functionality of the piece and lastly based on its look (artistic appeal).

Furniture should be judged only if you put it out there to be judged. Other than that no. I’ve seen rustic tables, chairs and benches, that while not conventionally beautiful, nonetheless have a certain beauty to them because of the service it provided, and because of the way they were constructed with skill. I’ve seen pieces made by students, and beginners like myself, that may be simple but also have solid joinery and carefully fitted parts because they were made with pride.

So unless it’s being sold either in a store or as plan no furniture should be up for criticism. Those who do critique privately made pieces are nothing more than snobs.

I have had experince in being judged at shows, although it was not furniture (colonial powder horns). The critiqueing is useful and helps to develope your skills,but can be sometimes hurt when you know you did your best and see work that placed that you feel is not of the same standard as yours. Also even though the judges supposedly dont know who the craftsman is. All craftsman have there own unique style which is just like putting your name on the product.So when you see the same people placing in the top and not to discredit there work you have to wonder why. All this said I still enter because what they might not like I know someone else will and that is how you get bussiness. Hope this helps coop

I have never entered neither shows nor exhibitions.

First, there haven’t been any shows etc. that I was aware of, where you could enter.

Second, I think I would be afraid to enter, because if someone judged my work to be ugly, I guess my feelings would be hurt. I guess I could try once, but if the first time wasn’t a success, then I am pretty sure that I would never ever submit another piece.

If I myself is happy with the piece and proud of it, then I don’t get anything out of someone telling me that it is wrongly constructed, ugly finished, a crappy finish and so on.

But I am glad that you explained how things are actually done in a jury, so maybe I’ll give it a go if there is a show near enough.

Best regards

Jonas (Denmark)